By Shalom Goldman, Duke University

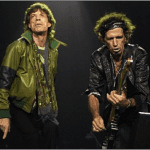

What do the Rolling Stones have to do with religion? Aside from the usual answer—that they are a religion in their own right for many rock and roll fans—they now find themselves in the midst of another kind of religious controversy. Surprisingly, it is a controversy that places, albeit briefly, Orthodox Jews and advocates for the Palestinian cause on the same side of an argument.

What do the Rolling Stones have to do with religion? Aside from the usual answer—that they are a religion in their own right for many rock and roll fans—they now find themselves in the midst of another kind of religious controversy. Surprisingly, it is a controversy that places, albeit briefly, Orthodox Jews and advocates for the Palestinian cause on the same side of an argument.

The controversy arose when the Rolling Stones announced in March that they would be performing in Tel Aviv. And while I’m sure that the Stones managers and the Israeli promoters expected considerable publicity, they didn’t anticipate that the very announcement of a Stones concert and the timing of that performance would create a firestorm.

At issue was a clash between the traditional Jewish calendar and the secular calendar of musical events. The news of the concert came right before Passover. In the Jewish calendar the holiday of Passover doesn’t stand on its own, but inaugurates a seven-week period of religious observance that ends in a lesser-known holiday called Shavuot (the Festival of Weeks).

Passover commemorates the Exodus from Egypt and Shavuot the revelation or “giving of the Torah” on Mt Sinai. In the biblical narrative these two events—the crossing of the Red Sea and the gathering at Sinai—are situated within months of each other. The giving of the Torah at Sinai is the culmination of the Exodus story. In rabbinic understanding the reason for the Exodus is to enable the Hebrew people to enter into a covenant with God. The famous forty years of wandering in the Sinai desert follow the dramatic events of the revelation, including the worship of the Golden Calf.

In 20th-century America, Passover has emerged as the most celebrated Jewish holiday; Shavuot is not even a close second. (Hanukkah has that honor.) Though only 15 percent of American Jews attend weekly synagogue service, the great majority of Jews participate in the Passover Seder, a celebration that resonates with the American Thanksgiving ritual. In Israel too, where weekly synagogue attendance among Jews is not much higher (perhaps 20 percent), Passover is the Jewish holiday. Its counterpart and culmination, Shavuot, is much neglected and in some sectors of the Jewish community virtually forgotten.

As scholar Michael Carasik suggested a number of years ago, one of the reasons for Shavuot being a “forgotten holiday” is sociological:

Passover is the occasion when families reconnect in a Jewish context; at the other end of the year, even non-Jewish calendars in the United States tend to note Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, and Gentiles have gotten used to their Jewish coworkers disappearing to attend synagogue services on those holidays. But Shavuot occurs at the beginning of summer. The school year is often over, and even synagogues expect to be less busy. Outside traditional circles, American Jews mostly ignore the holiday. Jewish Ideas Daily, 2011

But I suspect that there are deeper factors at work here. “Love” for the State of Israel has become the one unifying principle of identification for the world’s Jews. And from the mid-20th century onward the drama of the establishment of Israel against the background of the Holocaust has been understood by Jews—and by many Christians—as the biblical Exodus redux.

That modern drama, later reinforced by novels like Leon Uris’ bestselling Exodus, culminated in statehood and in the wars that followed Israeli statehood. Unlike the biblical Exodus, this contemporary story did not culminate in a subsequent encounter with the divine—or with the Law that Shavuot celebrates.

The astonishing success of the novel Exodus—a book that sold many million of copies and has never been out of print since it was published in 1959—was both a shaper of that perception and a testament to its power. Abstract concepts like divine revelation and covenant cannot compete with the living drama of the Jewish state.

Outside of traditional Judaism, and even to some extent within it, the commemoration of Shavuot has not been something to get excited about. Until this year.

In late March, a few weeks before Passover, Israeli producer Shuki Weiss announced that the Rolling Stones has agreed to perform in Tel Aviv’s Yarkon Park in June. This was a very big deal for the country’s legions of rock and roll fans, who never dreamed that the band would play in Tel Aviv. In the past few years, some American and European performers have signed on to a cultural boycott of Israel; thus, the news of the Stones impending visit was joyously received—even by those Israelis who weren’t necessarily rock and roll fans.

As soon as the concert was announced, opponents of Israeli policies launched an appeal urging the British rock group to cancel the event.

“We are writing to urge you to refrain from playing in apartheid Israel and not to condone Israel’s violations of international law and human rights against the Palestinian people,” the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI) said in a statement. “We wrote you previously, in 2007, after hearing of similar plans, and back then you did not play in Israel. We hope you will heed our call once again.”

“Why would you accept to perform in a country that is so deeply involved in war crimes and human rights violations?” the campaigners ask. “Performing in Israel at this time is morally equivalent to performing in South Africa during the apartheid era.”

But the Rolling Stones and their managers were not moved by this request. And the foreign opposition to the band’s appearance only heightened the expectations and determination of Israeli fans to hear Mick and the boys.

When the tickets (in the $200 range) went on sale they sold out in twenty minutes.

But as soon as the initial excitement was over, opposition to the Stones concert came from an unexpected quarter. A member of the Knesset, the Israeli parliament Nissan Slomiansky, an Orthodox legislator from the nationalist Bayit Hayehudi (Jewish Home) party, noted that the concert was scheduled for the night that the Shavuot holiday ends.

According to the Jerusalem Post article (“Bayit Yehudi MK: Rolling Stones fans can’t get no satisfaction on Shavuot”):

Knesset Finance Committee chairman Nissan Slomiansky (Bayit Yehudi) wrote a letter to the producer of the Stones upcoming concert, Shuki Weiss, pointing out that it is scheduled to begin just after the end of Shavuot. Slomiansky has received several complaints from religious people—including his daughters—that they cannot attend the show, as it is impossible to reach the Park Hayarkon concert site in time without violating the holiday’s Sabbath-like restrictions.

“Instead of being with their families and children, they’ll have to be in the streets of Tel Aviv to direct heavy traffic for the thousands of people who will come to see the show,” the Bayit Yehudi MK argued.

But the Rolling Stones and their Israeli promoter Shuki Weiss, who had been busy deflecting calls by pro-Palestinian activists to cancel the concert, were not about to bend to pressure from other interest groups—including Orthodox Jews.

And judging from the enthusiasm of Israeli Rolling Stones fans, who are bidding for any tickets that come on the market, they expect to have something akin to a religious experience at the Tel Aviv concert.

In this controversy Shavuot suddenly gets its day in Israel, a country where “secular” activities and the laws of traditional Judaism frequently compete for primacy of place. Shavuot’s sudden centrality at the center of debate makes strange allies between two critics of the secular state of Israel: pro-Palestinian activists and the Orthodox Rabbinate.

Bruce Springsteen has been known to open concerts with the greeting “welcome to the church of rock and roll.” But though the Tel Aviv Stones concert will no doubt be revelatory to Israeli fans, I can’t imagine Mick Jagger saying “welcome to the synagogue of rock and roll.” Though stranger things have happened in the Holy Land.

Shalom Goldman, Religion Department, Duke University