Biblical scholars often get accused of taking the life out of things. Would it be better to believe in something that is exposed as a fake? Not exactly debunkers, scholars are those who ask pointed questions of unstated assumptions. If some antiquities dealer claims to have access to material kept out of official hands, and is willing to charge you a lot for it, it’s best to call in the skeptics. It works the same in most fields that keep our society going. We need to trust those who’ve studied a subject in depth for many years. Devoted their lives to it, in fact. Many museum items around the world are forgeries and fakes. It’s not too often, though, that someone specializing in really old stuff gets called in to make an evaluation. There’s a risk involved—the risk of learning the truth.

It is indeed one of the roles of academics to complicate things that people oversimplify, as well as clarify and simplify things that people make unnecessarily complex or don’t understand because certain specialized knowledge is required.

It often happens that someone gets comfortable with the fact that their viewpoint aligns with what experts have to say, but that alignment had come about lazily or by assumption, rather than by them deliberately and consistently informing themselves. Eventually they embrace something that doesn’t reflect the scientific, medical, or historical consensus. And then suddenly they get pushback from an expert on the fact that in some area or on some subject they are in fact embracing pseudoscience or other pseudoscholarship. More often than not, they respond to this not by correcting their views, but by engaging in the standard denialist tactics that they themselves criticize when used by those with whom they disagree.

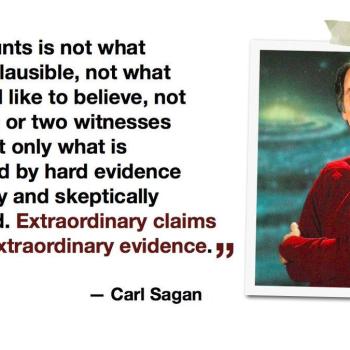

There is this a difference between that popular “skeptic” stance and what scholars do. Even if those who embrace the label “skeptic” tend to align with the views of experts more than others do, it remains the case that not all traditional knowledge is wrong. Saying “no” to everything is easy and the lazy way. Much harder is to look closely at evidence and decide the answer to each question on its own terms, sometimes accepting widely held views, sometimes rejecting them, and sometimes saying we don’t know. The key difference is being able to explain the rationale for one’s stance in terms of the evidence itself, rather than terms of its difference from the views of a certain religious tradition or the mass of humanity as a whole.

For more on the MOTB DSS see the Dead Sea Scroll Fragments Final Report as well as coverage by NPR, The Daily Beast, The Guardian, and others.

Paul Barford adds more to the above, and also wrote about another forgery, the Marzeah Papyrus

See as well Roberta Mazza’s letter to Brill about them in January

And on another modern forgery, have a listen to Mark Goodacre’s NT Pod episode on the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife. The next episode about how it was shown to be a forgery is also out.

Brandon Hawk told a story of researching manuscript provenance.

Of tangentially related interest see also: Flat Earths and Fake Footnotes