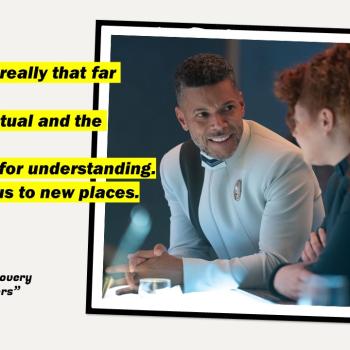

Given that I am currently writing something about afterlife and resurrection in the Bible and in science fiction, the ending of the episode grabbed my attention. I had been taking notes throughout the season and planned on blogging about it sooner or later, but the right moment never seemed to arrive until now. Even now, I feel conflicted about the colonialism on the show, as we see Picard as one time failed yet still determined and in the end successful type of the white savior. On some levels I felt that Picard’s prior failures, highlighted again in the season finale, represented something of a critique of that sort of colonialist confidence. But its message in that regard was at best ambiguous. When it comes to militarism, the message was much less ambiguous. While willingness to sacrifice oneself plays a crucial role, so does the carrying of a big stick, whether that be a beacon that can summon transcendent AI beings, Starfleet’s armada, or perhaps ideally both.

But on the intersection with religion I feel I’m clearer on the themes of the season. Death and resurrection were explicitly mentioned and highlighted at least as early as episode 2. By the third episode we had discussion of the benefit of a shared mythical framework; the insistance that when Raffi sees conspiracy it isn’t the way some people see ghosts or angels; an assertion (by an AI hologram) that Picard is a good man “on the side of the angels”; a human response asking to be spared “the juvenile Sunday school morality” (which is then nicely contrasted with “angsty teenage moral relativism”); and a discussion of whether certain things should be called “mythology”, “scripture”, or “the news.” I liked very much the idea that the Admonition that drove some would-be members of the Romulan secret society the Zhat Vash insane but set others on a crusade against artificial life was in fact a message for synthetics from others like them that have transcended the universe but continue to watch over it, and stand ready to aid their persecuted fellows. The depiction of humans as idolizing perfection, seeking to create it, and then feeling threatened by our creation seemed spot on. (See the day before yesterday’s post about Westworld for more on this theme.)

Knowing that the showrunners were not going to give up this cash cow after one season, I had a sense of where things might be going for practical reasons. It was nonetheless interesting how they chose to get there. And looking back, I love the way Patrick Stewart played Picard as old and failing so effectively that the new vigor in the final scenes was palpable. But the most striking thing was the scene in which we do not yet know whether Picard is in a brief dying vision, in an afterlife, a simulation in Data’s memory, or something else. In the foreground our attention is drawn to several statues of deities such as Ganesha and the Buddha. These are items with which Data has chosen to adorn the virtual dwelling place of his consciousness. And we learn that as a being with a potentially endless existence in that form, he wants his consciousness to be ended, not in the interest of dying, but because life only exists as such because it is finite. I am reminded of the conclusion of The Good Place. The idea that one should not desire immortality as a separate conscious entity, but the dissolution of the illusion of separateness, is a profoundly Buddhist one. Yet the presence of a Hindu deity more raises the theme of cyclical rebirth. One major emphasis in the finale is the history repeats itself. That’s why the fear of synthetic life isn’t “merely prophecy” – it is history, and history tends to repeat itself, meaning that past experience is a warning for the future. On the other hand, as Picard says, “Fear is an incompetent teacher,” and we are not obliged to follow the same path even when history does indeed seem to be repeating itself. The possibility of transferring one’s consciousness into a synthetic (but improved and healthy) duplicate of one’s body is more like Jewish and Christian resurrection than Hindu or Buddhist reincarnation. The choice of term “golem” for the template body that can serve as a vessel for the consciousness is an interesting one, given the significance of that term in Judaism as denoting an artificial being brought to life through the use of the divine name. The issue of whether in the end we still have Picard, or just a copy of Picard, confronts us, but no more and no less so than in the case of religious kinds of resurrection.

Perhaps the most striking blurring of the usual division between synthetic and organic life is the fact that an android (with the religiously significant name Sutra) has learned how to perform a Vulcan mind meld. If this is not suggestive of androids having every bit as much of a soul (or katra, if you prefer) as humans and Vulcans have in the realm of Star Trek, I don’t know what could be.

Returning briefly to the theme of colonialism and Picard as white savior, I felt that ultimately Starfleet showing up wasn’t simply a militaristic solution. It was a significant body of organic beings aligning and allying themselves with synthetics. However much the transcendent AI was depicted as a tentacled monstrosity almost unleashed from the pit of hell (a word used on the show for the apocalypse that the Romulans feared the AI would bring), these were godlike entities who were presumably not unable to emerge just because the beacon’s signal was interrupted. We should understand them to have seen what was happening, understood that it was one of their kind who asked for mercy for organics that were acting in friendship, and withdrew so as not to generate fear and hostility. Parce Domine.

What did you think of Star Trek: Picard’s first season? While I doubt anyone who read this post to the end hasn’t seen it, if you haven’t, you can do so for free for a limited time…

See further: