Some thoughts on blog posts related to one of my major fields of research – Christology and monotheism – as they relate to things that have appeared on blogs in recent days. Let me start with Keith Giles’ post about Jesus’ words from Psalm 22 on the cross. I agree with Giles that the widespread popular interpretation of Jesus’ words on the cross is misguided. But the “Messianic prophecy” approach he substitutes in its place is no better, especially given the doubtful status of some of the ways certain lines have been rendered into English to conform them to Jesus’ crucifixion. If one decides to envisage the historical Jesus reciting Psalm 22 on the cross, even though it is hard to imagine anyone being close enough to hear what he said who would also transmit the information to or within the Christian community, the most natural way to understand it is that Jesus recited the Psalm as an expression of his faith. The Psalm begins with a lament, but ends with salvation. Taken as a whole it may involve a sense of God-forsakenness, but it ultimately expresses trust and confidence in deliverance.

Dale Tuggy blogged about the death of Jesus as not involving the death of God, and criticizes the convoluted ways that some try to maintain simultaneously that Jesus the human being died, that God is immortal and cannot die, and that Jesus is God.

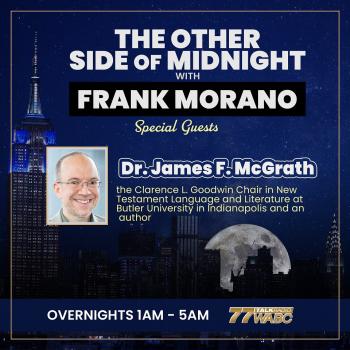

I also responded to a great question on my blog about what to do when I disagree with the consensus, as all academics are expected to in our original research to at least some extent. It was in a discussion of Christology, and here’s what I wrote:

It absolutely delights me that you’ve asked these questions. I’ve sometimes used myself as an example when advising people about following the consensus. The onus is on me to persuade my academic peers. Unless I succeed in doing so on points where I hold a minority or idiosyncratic view, stick with them. They’re probably right. On the particular question of Christology, however, I’d also recommend looking closely at what New Testament scholars have written on this topic, thinking primarily of those not working in academic institutions that impose a statement of faith on their necessarily conservative employees, since a dogmatically-imposed consensus isn’t an academic consensus, and in some respects is its opposite. Most mainstream New Testament scholars word their statements about Jesus in Paul’s writings and in the Gospels cautiously, so that even if they talk of his “divine status,” it may not mean “as a pre-existent person of the Trinity.” The terminology of “divine identity” is relatively recent, having been introduced into the discussion by Bauckham. Wright wrote about Paul “splitting the Shema” before that occurred, although in doing so he may have been a formative influence on Bauckham. But Wright’s statements say that Paul includes Jesus in the monotheistic statement of faith. He doesn’t say in so many words that Jesus is the second person of the Trinity. Splitting the shema, for Wright, means that Christians find themselves unable to speak about the one God without also speaking of Jesus. He himself seems to be navigating the waters between what it is appropriate to say as a New Testament scholar and what it is appropriate to say as a bishop.

Wright himself does adopt the language of identity. He also puts matters in functional terms in this famous statement: “My case has been, and remains, that Jesus believed himself called to do and be things which, in the traditions to which he fell heir, only Israel’s God, YHWH, was to do and be. I think he held this belief both with passionate and firm conviction and with the knowledge that he could be making a terrible, lunatic mistake.” And elsewhere, “the case for saying that Jesus thought of himself in a way which stands in continuity though not identity with what Paul and the other NT writers said about him grows out of Jesus’ basic kingdom proclamation and out of Jesus’ conviction that it was his task and role, his vocation, not only to speak of this kingdom but also to enact and embody it.”

Does my way of expressing the matter get things about right? What’s your sense of the consensus when it comes to Paul’s view of Jesus? How does that topic intersect with Good Friday, Holy Saturday, and Easter Sunday in your thinking, if at all?

Of related interest:

Splitting the Shema: A How Not To Guide

Is Jesus Included in the “Divine Identity” in 1 Corinthians 8:6?

(The preview image on this post is an Easter icon from Holy Trinity Church in Russia)