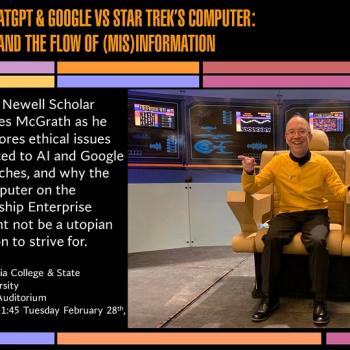

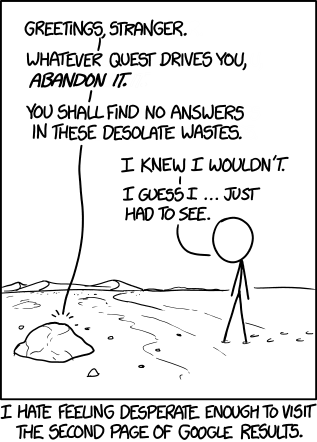

This post started with my coming across this XKCD cartoon (HT Marc Cortez) after having had some information literacy discussions in class just before, and having gone in class onto the second page of Google results:

I had used our desire to win arguments and prove others wrong using our smartphones and other devices as a starting point. Someone might dismiss our efforts if we take too long. And so, while it is better to go into the second, third, or fourth page of Google results than to settle for low-quality or ideologically biased material among the first page of results, it is probably better to use more and/or better keywords to bring good quality information onto the first page – or to use Google Books or Google Scholar rather than just the main Google search engine.

Then I spotted Ken Schenck’s post on discerning what sources to trust, followed soon after by Anthony Le Donne’s post with the subtitle “Don’t trust anyone.”

Reflecting on all this, and on the fact that there is ideologically-driven material masquerading as scholarship in abundance on the internet, I found myself wondering how to teach students to recognize it.

The key, I think, is skepticism. In scholarship, skepticism ought to be applied even-handedly, with the expectation that one’s own claims will themselves be subjected to rigorous skeptical examination.

When someone keeps trying to raise doubt about prevailing opinion, but is happy to offer as an alternative something that is at best possible, you are dealing with trickery rather than scholarship.

And so, as a fun in-class activity, I had students break up into pairs, and asked one to make a claim related to the Bible, and the other to doubt it. We also talked about things like Holocaust denial and young-earth creationism, as well as Jesus mythicism and several other topics more directly related to the Bible.

One point that I emphasizes is that anything can be doubted when it pertains to the past. And so we should not discard conclusions because they are not absolutely certain, but should seek conclusions that are genuinely probable, when all the possibilities and evidence have been treated with fair and reasonable skepticism. We should be on the lookout for those who try to get us to dismiss mainstream conclusions because they are less than absolutely certain, and yet offer us something that is at best a possibility in its place.

And perhaps, in addition to seeking to apply doubt and skepticism fairly, to one’s own view as well as others, scholarship involves stopping doubting when we reach the point at which it takes a greater leap of faith to disbelieve the results of our inquiry than to accept them?

Defining scholarship, and distinguishing scholarship from pseudoscholarship, is a challenge for students and the general public, and it affects some fields more than others.