Ryan Covington has posted on his blog about a subject we also discussed here, namely the question of whether there was a pre-Christian concept of a Davidic Messiah who, rather than ascending the throne and restoring the Davidic dynasty, is executed before he can do so. Ryan points to some of the well-known proposed counter-examples: Isaiah 53 (especially as translated in the LXX) and 4 Ezra.

Whether Isaiah 53 in the Septuagint rendering is more messianic in character than the Masoretic Text is highly debatable, despite what Covington says. But to the extent that it may be, this rendering does what the early targum also does (see Donald Juel’s discussion), namely downplay or eliminate the death of the servant, so that there is reference to him being led to death, but also to others being given for death and burial (presumably in his place), and his subsequent success.

No one would have considered it impossible for a would-be king to face hardships on his way to regaining his rightful throne. (On this see the convenient discussion and parallel translation in Messianism in the Old Greek of Isaiah: An Intertextual Analysis by Abi T. Ngunga.)

My favorite part of his post is where Covington uses the kind of historical reasoning that mythicists reject when it suits them to do so. He points out the unlikelihood that the author of 4 Ezra borrowed an idea from what would still have been an obscure Jewish sect in his time. Indeed, that may be relatively unlikely -but it is far more probable than that the author of the Gospel of Mark, writing a decade or two after Paul, turned a purely celestial figure into an earthly human one with no indication that it might be controversial to do so or that he was changing the nature of Christian belief. And so I am all for the use of such historical evaluation of probabilities, and with mythicists would do so in a consistent manner rather than the usual selective and obviously self-serving one.

Some of what Covington mentions is not relevant, since no one disputes either that Judaism eventually developed room for a suffering Messiah, or that anointed ones (when not referring specifically to the hope for the restoration of the Davidic line to the throne) could suffer and die. It would surely have had room for a successful restorer of the Davidic dynasty to die, and be followed on the throne by his son. And in the case of 4 Ezra, a successful Messiah, after a 400 year reign, eventually dies along with the rest of humankind as the prelude to the resurrection. That is clearly not the same thing as an alleged Davidic Messiah who is crucified without restoring the dynasty of his forefathers, whose followers insist that God enthroned him in the heavenly realm, unseen by most and thus a seeming failure.

Israel Knoll’s reconstruction of the fragmentary “Vision of Gabriel” is a subject of much ongoing scrutiny and debate, and so I won’t tackle that here, since a hypothetical reconstruction is scarcely the sort of evidence we need to settle a matter like this one.

I don’t see anything in the evidence Covington presents which suggests that what early Christians said about Jesus – that Jesus was the anointed one descended from David, despite not having installed himself or his son on the throne in Jerusalem – would have been anything but controversial in the context of the Judaism of that time (as perhaps in any other). Despite what Covington says, we are not particularly disadvantaged by a paucity of relevant sources. And we also have the broader context of human thought, which generally considers being killed before installing yourself as king to represent failure.

And so, as has been said before on countless occasions, the most likely reason for Christians coming to treat the cross of Jesus as success is not that they took up something already existing and widely accepted, nor that they invented this counterintuitive if not indeed oxymoronic view and tried to persuade other Jews to accept it. The most likely explanation remains that Christians were attempting to deal with the actual crucifixion of someone they strongly believed was the Davidic anointed one, and found ways of putting a positive spin on it, by turning Jesus’ apparent failure into a salvific moment in the divine plan.

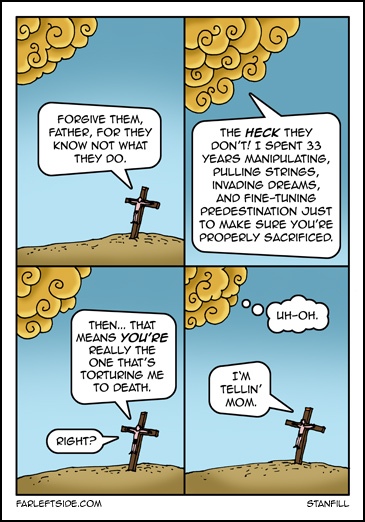

Of related interest, The Far Left Side (HT Hemant Mehta) had a cartoon that highlights some of the problems with seeing the crucifixion as both an act of human wickedness and part of a divine plan: