Every election is a negotiation. And the most dangerous thing for any candidate, whether he or she ultimate wins or loses, is speaking a language that excludes part of the electorate. For the loser it is because it means losing touch. For the winner it means being out of touch.

I spent most of my adult life in non-English-speaking contexts. As a result I have extensive experience in being part of conversations where I could not fully participate because my capability in that particular language was limited. I know what it is like to sound like a barbarian in the midst of an elegant and refined conversation in Malay. I know what it is like to sound like I’m an under educated nine year old in the midst of an academic conversation in German.

Whenever language is deployed at all it both includes and excludes people from the discourse. Sometimes that exclusion seems unavoidable. Academics like myself frequently use technical language forms that are usefully precise, but which affirm our social status and excludes others. The very act of producing this blog follows a certain model of rational discourse that creates a domain that includes and excludes people not familiar with its rules.

And I haven’t even mentioned non-verbal behaviors that include and exclude.

This said, consider the substantial portion of the US population, enough to elect a President, that has felt itself excluded from public political discourse.

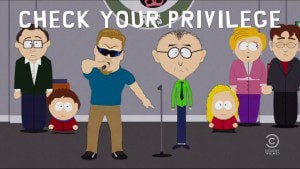

One form of felt exclusion is what those excluded speak of as “politically correct” language. Such language (which de-legitimizes a range of terms and expressions related to race and gender) was created precisely to include those who felt that excluded by such terms and expressions. And within the subculture that created it the intention seemed virtuous enough and the rules simple enough that it should be easily adopted by everyone. Why would anyone want to continue using language that excluded racial minorities and women?

Overtly no one. Yet like all forms of language, that of political correctness varied from situation to situation and in many cases sought to overthrow longstanding habits that weren’t easy to change. Getting rid of racial slurs was relatively easy, and they were excised pretty quickly from public discourse. Political correctness with regard to gender was more difficult, if only because gender exclusive language forms are more deeply embedded in our language. It still baffles many of my students both male and female.

As importantly, politically correct language never seemed to take into account language that excluded by its use of blaspheme. Astute politicians might avoid it, but blaspheme was the bread and butter of some of their supporters, people who would never use excluding language with regard to race and gender. This could make the development of pc language seem like less an effort to create a universal language of inclusion than an elite effort to shift the boundaries of inclusion and exclusion within the language to exclude those offended by blaspheme.

Nor is it just politically correct language that excludes. Part of the language of American political discourse for a long time has been the language of street protests, public shows of solidarity, and confrontation with authority. This language is rightfully seen as the language of those otherwise rendered inarticulate by social marginalization and an exclusionary media.

However, it is also a language that many Americans cannot themselves use well and the deployment of which makes them extremely uncomfortable. So when it becomes the focus of media attention, and becomes central to political discourse as has happened in the last several years, those Americans find themselves excluded from this particular form of political speech. And worse, despised by self-identified activists precisely because they do not choose to join into that particular conversation.

What this election has made clear is that Americans do not really have a shared language of political discourse, one that includes everybody and excludes nobody. Politically correct language and the language of the street were an effort to create such a language. But they have been only a partial success. Worse, those who spoke them fluently eventually quite listening to those who couldn’t. We dismissed them as backward, or naive, or ignorant. Not so different from the way an Austrian University professor would have turned away from my efforts to explain in German my views on Schiele’s art.

The vote is the one language everyone can speak. And the vote on Nov 7 should be a revelation to both sides – because it was close. Many of the marginalized who were finally beginning to feel part of the political conversation find themselves today excluded and wounded. For some there is a legitimate fear of physical harm. Many others feel that they have suddenly found their voice. Unfortunately that voice hasn’t merely been politically incorrect, it has perpetuated cruelty and harm. This is not a sustainable situation.

We need to find a common language of political discourse, one that reaches across significant cultural divides. Until we do we will continue to stumble politically into endless, fruitless, conflict that advantages no one, and continues to leave the most vulnerable in our society marginalized.