Remembering Progressive Evangelicals: The Clapham Sect

*Note: I you choose to comment, please keep your comment relatively brief (no more than 100 words), on topic, addressed to me, civil and respectful (not hostile or argumentative) and devoid of photos or links.*

Have you ever heard of The Clapham Sect? Probably not. Unless you are a church historian (professional or amateur) and one who specializes in evangelical history, British social and political history, the history of abolition, etc.

I believe this is an example of “history that deserves to be remembered.”

Today, in the third decade of the 21st century, most Americans think all evangelicals are politically hard-core right-wing people and many of them thinks being against social reform or progressive politics and economics is simply part of being “evangelical.”

Some political commentators have contributed to that mistaken impression. One in particular, whose names I won’t mention here, publicly warned American Christians to avoid churches that talked about social justice.

As a historian of Christianity and especially evangelicalism, I can assure you that there have always been counter-examples to that mistaken impression. When I was being formed theologically in the 1970s several groups of evangelicals formed into networks and organizations to oppose the War in Vietnam (America’s involvement) there and to promote civil rights, equality for all people, women’s liberation from oppression, etc. They/we were labeled “The Evangelical Left” by conservative evangelical leaders and thinkers including Carl Henry and Millard Erickson. Our publications included The Post-American which became Sojourners and The Other Side. My late friend Donald Dayton wrote a bombshell book entitled “Discovering an Evangelical Heritage.” The book drew heavily on the work of evangelical historian Timothy Smith. It demonstrated conclusively that before D. L. Moody, so throughout much of the 19th century, many conservative, evangelical Christians in America were social progressivists including, among others, B. T. Roberts, founder of the Free Methodist Church.

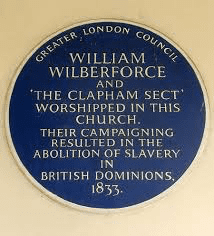

Somewhere along my journey away from fundamentalism and socio-political conservatism mixed with evangelical Christianity, I discovered The Clapham Sect which was not really as “sect” at all. Some have preferred to re-label them “The Clapham Group.” The best known member was William Wilberforce. This was a group of mostly English evangelical social reformers who pressed for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade. They were encouraged by former slave ship captain and hymn writer John Newton. Most of the members of the group were evangelical Anglicans. (Yes, there have always been and still are evangelical Anglicans. Think J. I. Packer, Michael Green, N. T. Wright and others.)

The Clapham Sect met on a regular basis to strategize and encourage each other to pressure the British government to become more socially and political progressive including abolition of slavery and equal rights for women. Many have credited them with laying the groundwork in the UK for the abolition of child labor and for state support for the indigent—other than simply throwing them into “work houses.”

Members of the “sect” were not communists or socialists in any modern sense, but they saw an England that they believed could be more compassionate toward the weak, the vulnerable, the oppressed and worked toward social policies that abolished such things a unearned privilege in the courts.

There were similar groups of progressive evangelicals in the Scandinavian countries and in America. Evangelical Methodist B. T. Roberts broke away from the Methodist Episcopal Church because of its reluctance to denounce slavery, its failure to ordain women or let them preach or be pastors, and its growing tendency to favor the rich and powerful in American society. As I mentioned earlier, he founded the Free Methodist Church which in 1860 was one of the first Christian denominations to have ordained women pastors and preachers. Roberts was also an outspoken abolitionist along with evangelical Charles Finney and other especially northern evangelicals.

What about today? The power of the media has transformed the word “evangelical” to the point where a progressive Christian (and here I mean socially and politically progressive) automatically cannot be considered an evangelical. And many progressive evangelicals have succumbed to that and dropped the label “evangelical,” handing it over to the neo-fundamentalists and “Christian” white nationalists. “Trumpism” and “evangelical” have become almost synonymous. That is the media’s fault.

The fact is that evangelical Christianity is a spiritual-theological type, not a monolithic movement or even a movement at all. But I have said and explained this so many times here that I feel like I’m beating a dead horse. I will stop now. But know that I am very angry that my evangelicalism has been hijacked by neo-fundamentalists and socio-political reactionaries who idolize America and buy into Social Darwinism.