Christian Smith, The Bible Made Impossible, Chapter 6: “Accepting Complexity and Ambiguity”

There is no chapter in Smith’s book with which I agree more than this one. While I don’t think his prescriptions here will go very far toward reducing pervasive interpretive pluralism (PIP), they are of paramount importance for evangelical honesty (toward the Bible) and generosity (toward each other and other Christians).

I cannot recommend this chapter highly enough; I wish every evangelical (and that’s a pretty broad concept for me!) could read this chapter if nothing else. Of course, as with other chapters, there’s nothing that new here. The novelty of Smith’s book and this chapter lies not in any innovation of concepts but in the way old concepts are packaged and presented.

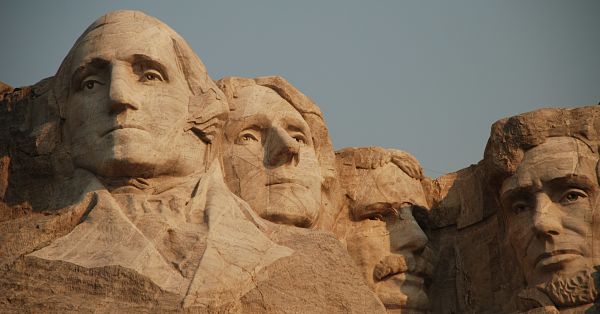

A lot of the material in this chapter I learned in seminary. I was fortunate enough to attend a very sane, moderate, even sometimes progressive evangelical Baptist seminary (North American Baptist Seminary in Sioux Falls, South Dakota—now called Sioux Falls Seminary). My professors were full of good, strong, common sense about the Bible and theology as well as steeped in the best historical and contemporary scholarship. Sometimes I’m tempted to say that everything I ever really needed to know I learned in seminary. It liberated me from fundamentalism, obscurantism and anti-intellectualism and introduced me to this (Smith’s) kind of broad, generous, common-sensical evangelical Christianity.

I’ll have to admit up front that I MIGHT be biased in favor of this chapter because I’m favorably named in it; Smith makes use of my distinction between “dogmas,” “doctrines,” and “opinions”—something I first published in the little book Who Needs Theology (IVP). However, I don’t really think that’s the case. Even were I not mentioned in the chapter I would find almost total agreement with it.

The first part of the Chapter 6 is “Embracing the Bible for what it obviously is.” Smith says “One of the strangest things about the biblicist mentality is its evident refusal to take the Bible at face value.” (127) He accuses evangelical biblicists of creating a “theory about the Bible [that] drives them to make it something that it evidently is not.” (127) Smith urges evangelicals to be satisfied and come to terms with the actual phenomena of Scripture rather than imposing on it a theory of inspiration, authority and inerrancy foreign to it as an ancient text containing many different literary genres. In the second section of the chapter, entitled “Living with scriptural ambiguities,” Smith unfolds what he means. There he says “There is no reason whatsoever not to openly acknowledge the sometimes confusing, ambiguous, and seemingly incomplete nature of scripture.” (131) Then he explains “All of scripture is not clear, nor does it need to be. But the real matter of scripture is clear, ‘the deepest secret of all,’ that God in Christ has come to earth, lived, taught, healed, died, and risen to new life, so that we too can rise to life in him.” (132)

In contrast, Smith argues, too many evangelicals (not all) have imposed on Scripture an expectation and then a demand that it be perfect in every way by modern standards suitable to (for example) university textbooks. The Bible simply isn’t that. It is not a set of inerrant propositions waiting to be harmonized and systematized into something like a philosophy. Rather, it contains ambiguities, uncertainties, apparent contradictions, mysteries, etc. At the end of this section of the chapter Smith quotes the great Dutch Reformed theologian G. C. Berkouwer (who I use in Against Calvinism against the radical Reformed theology of the “new Calvinism” in America) approvingly: “the confession of perspicuity is not a statement in general concerning the human language of Scripture, but a confession concerning the perspicuity of the gospel in Scripture.” (133) To that I say amen!

In the next section of the chapter (“Dropping the compulsion to harmonize”) Smith gives a case study in how biblicism’s theory of Scripture simply does not fit the phenomena of Scripture. His case study is drawn from Harold Lindsell’s infamous (that’s my value judgment but not mine alone!) 1976 book The Battle for the Bible. There Lindsell, a militant inerrantist who wanted moderate to progressive evangelicals fired from their teaching positions at evangelical colleges, universities and seminaries, argued that if we believe the Bible to be inspired, authoritative and inerrant (three adjectives he linked inseparably together) we must believe that Peter denied Christ six times before the cock crowed on two separate occasions. This was Lindsell’s attempt to harmonize the four gospels’ accounts of Peter’s denial. This is just a case study in making the Bible impossible.

Smith concludes that “the Bible, understood as what it actually is, still speaks to us with a divine authority, which we need not question but which rather powerfully calls us and our lives into question.” (134) Well said! It’s important to note that Smith does NOT say that all harmonizing attempts are bad. “In some cases, to be sure, harmonizations of biblical accounts may actually be right.” (134) It’s just that harmonizing is usually not necessary. (134)

I agree with Smith’s overall point in this section, but I would push a little further than he does with respect to the value of cautious harmonization of biblical teachings and stories. They can’t all be harmonized and we shouldn’t even try—especially when we’re talking about non-essentials of the faith. But I have a friend who teaches New Testament at a Christian college who occasionally picks on me for going overboard with harmonization. He even goes so far as to argue that the Bible teaches BOTH absolute, unconditional predestination AND free will (as power of contrary choice) and the necessity of free cooperation with grace. That is, he believes the Bible teaches BOTH monergism and synergism. And he disdains every effort by theologians to systematize these into a coherent soteriology. For him, just to give one example, Philippians 2:12-13 is a contradiction and we simply have to embrace it and not try to harmonize these two verses. I disagree because I see no problem; it takes no “forced harmonization” to harmonize them into a coherent soteriology of prevenient grace and free human cooperation with grace. I just don’t see the problem there whereas he thinks I am forcing harmony where none exists.

Also, New Testament scholar friend thinks I’m simply crazy to think there is real consistency and harmony between the various accounts of the giving of the Holy Spirit in the gospels and Acts. One gospel has Jesus breathing on his disciples BEFORE his ascension and giving them the Holy Spirit. Acts has the Holy Spirit descending on them on the Day of Pentecost. My friend insists these are disparate accounts of the same event. I disagree. To me that’s not much different from Pannenberg’s (with whom I studied and I heard him say this) claim that the story of Jesus’ transfiguration is a “misplaced resurrection story.” I haven’t discussed this one with my friend, so I don’t know what he would say. We kind of agreed to disagree and leave the matter alone (at least for a while).

I think it’s fairly obvious (though I wouldn’t call someone a heretic who disagrees) that Jesus gave his disciples the Holy Spirit to indwell them and be with them before Pentecost but on the Day of Pentecost the Holy Spirit filled them (“enduement with power” as Pentecostals call it). This fits with some of the stories of Spirit infilling (e.g., of people already believers) in later parts of Acts. I don’t see any forced harmonization there. But I do think Lindsell’s explanation of Peter’s denial of Jesus represents forced and completely unnecessary harmonization. I’m not sure what Smith would think of my rather modest and moderate approach to harmonizing Scripture. He very well might not like it. But I think we should harmonize when we can (e.g., the Arminian take on Philippians 2:12-13) and leave diversity within Scripture alone when we can’t harmonize without distortion.

The next section of the chapter is entitled (subheaded) “Distinguishing dogma, doctrine, and opinion.” Of course, I agree whole heartedly with Smith in this section! J Especially when he criticizes those biblicists who set up scripture readers “to assume that once they have decided what the Bible appears to teach, they will then have come into possession of absolutely definite, divinely authorized, universally valid, indubitable truth. And that truth will be equally valid and certain for every subject about which scripture appears to speak, whether it be the divinity of Jesus or how to engage in ‘biblical dating’.” (137) Smith rightly calls on evangelicals (and all Christians) to exercise a greater degree of humility about their secondary beliefs, their denominational distinctive (or distinctive of a certain tradition) and put beliefs in their right categories according to the clarity of Scripture about them and the certainty possible with regard to them. He cautions that “The point is not that every particular Christian group and tradition needs to strip itself of all its distinctive.” (138) The point is a changed attitude toward levels of importance of biblical teachings and those who disagree about secondary matters not necessary for salvation or even for authentic Christian living.

In my opinion, this recommendation could go a long way toward overcoming many of the controversies among evangelicals. We (the evangelical community in the U.S.) are being torn apart over secondary doctrines and teachings such as predestination, the inerrancy of the Bible, the possible salvation of the unevangelized, etc., etc. Of course, fundamentalists and neo-fundamentalists are not likely to give up insisting that their views are the only possible ones in light of a valid interpretation of Scripture, but my point (in addition to Smith’s) is that evangelical LEADERS need to speak out openly against this internecine war going on among evangelicals which is almost exclusively being fomented by conservatives.

I well remember when Jay Kessler, then head of Youth for Christ and president of Taylor University came to the college where I taught and decried this growing tendency among evangelicals to shoot at each other (figurately speaking, of course) over relatively minor points of doctrine and practice. Too bad he didn’t write an article and have it published in Christianity Today or something! He was a powerful voice for moderation among evangelicals for many years, but either people weren’t listening or he just didn’t raise his voice loudly enough. But I know he was passionately opposed to this tendency to major in the minors as he saw what I call neo-fundamentalists taking over the evangelical community by creating fear of heresy among the untutored laity and pastors.

The last two sections of this chapter are headed “Not everything must be replicated” and “Living on a need-to-know basis.” Smith’s theses are that not everything practiced or even promoted by biblical writers, even apostles, must be practiced today. In other words, there is cultural conditioning in the Bible. And that “In his wisdom, God has chosen to reveal some of his will, plan and work, but clearly not all of it. To the extent that the Bible tells us about matters of Christian faith and life, it clearly does not tell us everything. It certainly does not tell us everything we often want to know.” (141) “Christians would do well to simply accept and live contentedly with the fact that they are being informed about the big picture on a ‘need to know’ basis. … if God has not made something completely clear in scripture, then it is probably best not to try to speculate it into something too significant. Let the ambiguous remain ambiguous.” (142) Again, amen to that! There’s a place for reverent speculation in theology, but it MUST be labeled that—speculation—and not touted as dogma or even doctrine. And I can be firmly convinced that I am right about some matter I think Scripture “clearly teaches” that is not central to salvation and Christian faith WITHOUT implying that those who disagree are subchristian or even subevangelical.

So let’s be specific about this chapter. What’s a case study in what Smith is opposed to here that violates his recommendations for being realistic about biblical ambiguities and secondary matters of doctrine. Well, I already mentioned The Battle for the Bible. But I would add (this is my own opinion, of course) D. A. Carson’s book The Gagging of God (1996). I saw in it a full frontal assault on fellow evangelicals who, in my opinion, Carson did not really even understand. A case in point is his treatment of Stan Grenz. I won’t go into details here as I have already done that in Reformed and Always Reforming which I wrote largely in response to Carson’s book.

In my opinion, this chapter of Smith’s book is crucial to a better, healthier, more reasonable approach to Scripture and doctrine than the one all too common among especially conservative evangelicals. It won’t fix the problem of PIP, but it could help evangelicals (and others) achieve a more balanced and sane approach to Scripture and doctrine.