Part One

I was first assigned to the beam-cutting station, but I asked to be reassigned. I wanted to weld. It seemed honorable and I wanted to be somebody. But I guess no ones asks to be a welder once they get to the cutting stations. I was given the materials: gloves, sleeves, apron, mask. I needed boots. No tennis shoes. I don’t recall the details or the exact time, but I passed an initial inspection of some kind. I was first assigned to be a go-fer, which sucked. I took naps and wasted a lot of time. I was then assigned to weld with a rowdy crew who only began to accept me when they heard I liked to drink lots of Keystone Light. We had a good time and they taught me a lot about politics. They were a tribe. Their best welder, the leader of the pack, knew the shop needed him bad, worse than he needed them, so he’d work until he decided he had enough overtime pay and wouldn’t show up again till the next pay cycle. Unless there was a rush order or things were backed up: then he’d make them pay him time and a half. He was shrewd, but not an asshole. He knew he could make more money elsewhere, but he had things under control here. He ruled his tribe as well as anyone I’d ever seen. There was a talented up-and-comer who had just bought a brand new Dodge pickup and had a knack for getting his girlfriends pregnant. There were inside jokes and initiation pranks. I didn’t fall for them and they respected me for that. But I saw this poor, stupid soul almost crack his skull doing the broom-kicking competition. They admired intelligence, no matter where it came from, books or whatever, and they hated an idiot. They asked me what philosophy was and I was in no position at the time to tell them, but I think I managed to do okay. I got a strong sense that they didn’t want to be patronized, these were intellectual men of a certain, alternative cut. They carried themselves with a fierce dignity. Not insecure like academics and writers and office workers. Scared me sometimes. They horsed around all the time, but they were also serious. Life and death kind of stuff. We were doing dangerous work: no place to joke around when a ton of steel could fall on someone’s leg. The shop floor was segregated between whites and mexicans, with younger mexicans, who only spoke English and hated the older Spanish-speaking mexicans for hating them, in-between. One of my roommates was one of the young ones: browner than me but only knew how to cuss in Spanish, and his accent was awful. I was different. Yes, I was a college boy, but I also liked to carry-on with the rednecks and could speak fluent Spanish with the wetbacks. I was improving at welding. I was a terrible in high school shop-class; I never tried hard enough. The big beams were great to weld because you didn’t have to worry about burning through the metal. Thick and hot. You could go slowly and deliberately and run a beautiful, glowing scar down those seams. After a few weeks, I was reassigned to learn how to weld aluminum, a more delicate medium. Next to me was the work station of an older mexican man, who sold tacos during break and functioned as something between a court jester and a sage. He was the fool of the shop, in Cervantes and Shakespeare’s literary sense. Chema. That was his name, or at least what everyone called him. I was sent to help him one day, because he was running behind on his quota. 25 frames per day. Not too strict, but more than less. Each frame had to be approved. The inspector was a nice, good-old-boy who’d been doing this forever, he probably started off as a welder; he’d measure the angles and lengths and check the welds, circling the bad ones with chalk to do over. We made stadium bleachers. Summer temperatures ran at about 100 F; inside the shop was hotter. When you started welding, you had to turn off the fan, to prevent the blowing air from ruining your weld. The bead was supposed to be a thousand degrees hot, and it felt like it. “Keep your chin down, son.” The first week I had a tender, burnt triangle on my neck, peaking down to my upper chest from raising my chin too much and exposing myself to the white-hot welding bead. So it got plenty hot, from all directions. Chema didn’t seem to sweat much, he was conditioned for this work, but he was terrible at measuring and reading the plans to create the frames. He wasn’t stupid: he was going blind. Everyone one knew it, even the foreman, but no one was going to put him out like that. They sent me there to read the charts and let Chema teach me how to tack down the L-joints to create a pattern on the work table for making support frames. The frames were small, so the station didn’t need a big lift, just a small overhead for picking the frames off the work table. You had to move quickly on these thin beams, otherwise you’d blow holes in them. The frames were all but fixed to the table, to ensure proper measurements, so you had to be able to weld in all directions, at all angles, without moving the materials. Right side up and up side down. Horizontal and vertical. Chema taught me all that stuff, somehow. He liked me because I was “un artista.” An artist, a musician. In the back of the station there were things Chema built with leftover steel. A chair he sat in a lot. Three towers of cassette tapes, filled with music that blared from his station all day long. He was the deejay for the mostly mexican cutting-stations of the front of the shop. He didn’t just play Norteño or conjunto music — trova, cumbia, all the variations of salsa and merengue. He played it all. A Latin music expert. He knew the names of all the rhythms and patterns. He liked corridos, because they were historical and sad. He was a cultured man. He danced around, foolishly, as I did almost all the work. He was my muse. I found the Latin clave in that hot welding station and it’s infected the way I hear everything. When a 4-4 soul groove is playing, I hear a 2-3 clave and it makes my phrasing stand-out and sound interesting. He loved to talk to me about music and food and women and how stupid everyone — white and mexican alike — in the shop was. How he woke up at 3:30 every morning to make his tacos and got in by 5 to ride the clock until 6 when he would start making coffee. (He had his coffee at 4, at home. Good coffee.) He said that selling tacos was all about not being lazy and profiting from the laziness of others. To him every taco he sold was an insult to the customer’s character. He therefore insisted that I get mine for free. I had a close call where I almost lost my finger tip. He was horrified. How could I risk my hands, my art, my guitar for this? My maternal Granfather — Grandpa Montaño — came to visit one day, I don’t recall the details of why he was there, but he saw me covered in soot and sweat and I could tell he was proud of me. I proved that I could work hard in a way he could understand. He treated me like a man and told me to get back to work. Never felt sorry for me. That made me feel like I was somebody. I got what I came for so I took Chema’s advice and left that dangerous, dancing workstation for an easy, stupid job tending kids at the YMCA for the last month and a half before I returned to school in Ohio.

Part Two

Bilingual Benefits Representative. That seemed pretty good. What was it? Target Corporation, corporate headquarters. Sounded important enough. Fourteen dollars an hour, plus ten percent off at Target stores and lots of perks to rent limousines and go watch WMBA games. (I did both.) I was teaching Spanish. 26k a year before deductions. With my commute and everything else I was beginning to feel like Tolstoy’s Ivan Ilych: underpaid and under-appreciated. Unlike Ilych, I actually was being underpaid — like everyone else at that small parochial school. I put on my suit and interviewed. A breeze. In training I quickly realized that everything was a joke, but fun. Teaching had come easy, but this was easier. I expected it to be more serious and harder. I gave a presentation during one of our innovative group learning projects about offering puma rides. Everyone laughed. It boosted morale. My reviews were sky high. One of the trainers pissed me off so I got him fired through my exit interview and evaluation. No one liked him anyway. We all started on the general call floor. English calls only, there was more training required for Spanish calls. The trainer was nervous because her Spanish wasn’t tip-top and asked for my help. I already felt like I was being groomed for a promotion. Great. Shirt and tie, everyday. Everyone was counting down till they could transfer out. Except the older people, they were there for life. Programmed. Not us. We were fresh out of college, looking for a shot at middle management. We’d dream during lunch hour, in the corporate cafeteria. Our in- and after-call times were to be short, but not too hasty. Sound natural saying the prescribed greetings and following all the steps, that’s the key. Everything was recorded. Surveillance somehow made things feel more official and dignified. This was Target: everyone is a team member. This means that everyone was treated like a chimpanzee. Training. Bananas. When I knew the answer, I was observed to make sure that I looked it up anyway, and recited it word for word from the manual. That way, everything we said could be held accountable to the same, standard language. “Even if it’s wrong, say it anyway and report it, then it will get fixed for everyone.” (Everyone, that is, except the person who got the wrong advice about her family’s health insurance.) The cubicles were pretty spacious, you could twirl around in your chair. When calls were slow I’d read and write and goof off. There was constant morale boosting — team building activities! — going on: I started playing all the stupid games and even invented a few. I brought a little rubber ball, the kind that bounces everywhere and forever, and my buddy and I played a game to see how many times it could bounce without breaking anything. If you could get it trapped under a desk, it would bounce at least twelve times. Win. It got out and flew into our floor supervisor’s cubicle one day. She was annoyed but didn’t really care. Even thought it was funny. I realized that her job was even dumber than mine was. Every week we’d have a short ceremony where our stat reports would come out and we’d find out who rated the best that week. If you got over 90% they gave you a little sheet of paper. People kept these pinned on their cubicles. Badges of honor. Corporate helmet stickers. I won a few. But soon I realized how hard it was to go below 80%. I’d leave my phone off the hook, explore the new building or sit on the toilet reading a book: it took a long time to drop my stats into the 70’s. Facebook wasn’t blocked, but it wasn’t really permitted. Me and another buddy who worked downtown would IM each other on Facebook, writing backwards — that way, no one could read what we were writing and it was another fun way to make the time pass. I started job searching. I couldn’t wait nine months for a promotion. Four months was long enough. I regretted leaving the school. I was applying too low and holding myself back (back from what?), all the managers were either infantilizing or acted like well behaved children. I needed more money. This pay was nothing here. I saw people’s salaries, even the ones of the store workers making seven dollars an hour, with no benefits. No one cared about anything. My calls were getting worse because I would hangup on assholes and people I didn’t care to talk to. One person reported me for telling them they were killing my stats when they were being idiots about the fact that I couldn’t send them a screen shot of their benefits page. It wasn’t in the manual!

Part Three

The opening details are mostly unimportant. The hiring process was convoluted and indirect. I quit my job at Target to work closer to where we lived, working on an IT project for Medtronic Corporation, as a consultant for another middle-man corporation. I had to get hired by both of them. Still an hourly employee, but making ten dollars more per hour. My official title, which I only learned after a week or two on the job, was something along the lines of a “coordinator.” Most of the employees were subcontracted from IBM, many of them from India. I was in charge of getting them on- and off-board. It was entirely different from Target. There was no job description or training; I was simply to figure out my job and do it as I saw fit and report to my supervisor and manager. Surveillance was very low, too. The person who had my job previously was hired as an official Medtronic employee, supporting the project manager. She was helpful and positive, but had left the position in shambles, largely because the person before her was incompetent. It was chaotic but liberating, at first. There was room to make some stuff up. Room to live a little. I never entirely understood what I was supposed to be doing and, honestly, I don’t think anyone else knew either. My manager was a wonderful man: a Spaniard from Asturias. A slender and tall widower, a cultured man with a thick Spanish accent and also a practicing Catholic. A rosary hung from his computer screen. He played bass at his parish. I was the only Spanish speaker in the building so we soon became friends. The only part of the job I understood was that I was to eat lunch with my manager and talk to him in Spanish about interesting things: books, feminism, music, guitars and songwriting, religion, and more. We would lunch for at least one hour almost daily and talk until we got back to his office. My cubicle was just outside his door. This relationship infuriated my supervisor, and she eventually tried to undermine me. My manager would hear nothing of it. He was convinced that my skills were being wasted and he didn’t seem to care what I was doing or not doing. He wanted me to be moved into a more serious, dignified position, where I could write and think about conceptual things the project was working on. I was not doing a lot and I was almost always faking it. All I did well was to correspond with our main contact from IBM — a French woman who never came on-site — and look important. I also liked to eat popcorn every day around three in the afternoon with the Indian IBM-ers. They all thought I was Indian, too, until one day I revealed that I wasn’t. They liked me enough anyhow to let me join them for popcorn whenever I pleased. The project itself was interesting: it was about trying to standardize corporate language and processes across three or four global headquarters. “Centerpoint” — that was the title. It was a centralizing operation, a Tower of Babel problem. I understood it quite well, actually, and think I could have helped, but not in my current position. The purpose behind the piles of money and workers was to increase communication through language and some procedures in carefully planned phases. As interesting as it was in theory, my day-to-day was becoming more and more tedious and my supervisor was out to get me. I was, of course, cutting lots of corners. There were whole assignments I was not doing. Like keeping a current map of everyone’s cubicle assignments and making sure that everyone who left the project didn’t have an active remote-access password. I built a huge spreadsheet and color-coded it. It was as absurd as Borges’ famous taxonomy in “The Analytic Language of John Wilkins.” As Ivan Illich would later put it (in Deschooling Society), my spreadsheet was irrationally consistent. I could explain it in meetings or in professional conversations because (a) no one listened or cared and (b) the color-codes and the Excel data gave it a sense of order and fake rigor. “Great work, Sam; keep it up.” By the end of my time there I was going on walks around the building, under the guise of checking-up on things (like my much neglected floor map). I think I first felt serious anxiety while working there. I don’t know why, but it made me feel like I was going to explode inside. Suffocating. Ohio State was recruiting me into their Ph.D. program at the time and I was also accepted at Syracuse, but, in my heart, I was still unsure whether I wanted to work here or not. I confided in my manager one day and he gave me his blessing. A classmate told me I should take the security and money and stay at Medtronic. “Take the money and run!” That was what he told me. But graduation and doctoral studies were still a few months away and I now hated my job. The doctor told me I was clinically depressed which depressed the shit out of me, clinically, I suppose. I couldn’t enjoy my lunch or popcorn anymore because my supervisor was oppressively vigilant and I was running out of fake jobs to pretend to do. Doing fake work is very taxing on the nerves. I began looking for other work that I could do as an independent consultant — some music, some translating, some other things here and there — to get us to the time when we’d move to Columbus. I never said goodbye, I just picked up my things and left. They could fire me on the spot any day, so I didn’t see why I should give them two weeks. I still don’t understand that. Plus, I wouldn’t need the references: I was making a clean break from corporate cubicles. I was going to the academy: back to the craftwork I so dearly missed. Not steel and dancing, this would be books and teaching.

Epilogue

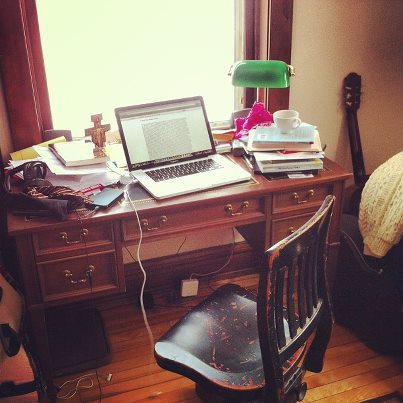

I was destined for the collar. Everyone seemed to see that, and believe it, too. Fr. O’Malley, the priest who converted my father and baptized me, would take me out for a steak dinner sometimes. He’d always say, “When you’re a priest, you can eat steak everyday.” That stuck. I love to eat. I felt obligated to say that I wanted to be a priest when I grew up. Not sure why, but I knew there was no firefighting in my future. I was a devout and precise altar server until I took over music ministry and liturgy planning from Jr. High into college. In high school there were vocation retreats and visits from the diocesan vocation director. I’d lived my entire life in rectories and church offices. I knew and loved and despised dozens of priests. I understood the vocation as well as any high school student could. Fr. Sam, a wonderful mentor to me, offered to pay for my college tuition—the implicit agreement was that I’d be ordained a member of the Society of the Precious Blood. I couldn’t do it. It wasn’t the fear of becoming a priest someday: that I could deal with, I’d been dealing with it my entire life. It had more to do with not wanting to let Fr. Sam down, a man I truly loved. As cocksure and bright as I seemed on the outside, I had no idea what I could do in college. No internal sense of competence or confidence. Always guessing. No one cared to tell me that I was over-preparing with my debate regimen and Georgetown didn’t mean anything to me then. After showing promise in competitive debate, a State scholarship and some philanthropic money sent me to Waco, Texas for two weeks. Baylor Debate Camp. Besides eating in the cafeteria of Hardin Simmons University before a playoff football game, I’d never seen a college campus before and I had no idea, really, what it would be like there. My roommate was Jewish. We were enrolled in the exclusive, “expert” tier. I was certainly no novice, but I probably belonged in the intermediate group. I figured I’d never get to do this again, so I’d better see what the best people were doing. It was the summer before my junior year. The year earlier I’d beaten the best debater in our district, a senior from Ballinger, Texas, for the final spot at regionals. She and I had debated in my very first tournament the year before that, when I was a freshman. She dusted me in the semi-finals. But I was in over my head at regionals. I needed better content and polish. Even my proud, paraplegic coach admitted that I needed outside help: debate was new at little Brady High School. This was a first for him, too. He had played and coached basketball before his accident and won state titles. Now he was my coach and we were going to win trophies and medals and go to state together. So I needed to get better. Lincoln Douglas debate is a one-on-one combat over value propositions. The foundation was always philosophy, or some legal derivative. I needed to learn about philosophy and get more training in the rhetorical techniques being used by the big-league, national circuit debaters. There were kids from all over the country. Baylor University. Walking the campus was something out a dream or a movie I’d never had the data to imagine or process. It felt free and frightening and I knew I would have to go to college someday to spend more time at such an enchanting place. This was better than church. I’d never heard of a coffee shop before, but I did have a taste for coffee: prayer meetings always served coffee and Dad always let me drink it, with milk and sugar. “Common Grounds” was dark and, on that night, packed with debate nerds. I had money, I got an envelope with $215 dollars in it, for spending. I had no idea what to do with that much money in such little time, but I felt obliged to spend it there, at Baylor, not to try and save it and take it home with me like I would usually do. Coffee was expensive. I learned the ritual of ordering and waiting and where the bar was with the napkins and stirring sticks and salt-shaker things to add flavors to the coffee. Cocoa. Then conversation. The dance. Sparring. I befriended a group of novice-level debaters who thought I was more important that I really was, and I acted like it. The first morning opened with a welcome, followed by a lecture from a professor in the communications department. He was wearing a blue Oxford shirt with huge, sweaty pit stains. He spoke passionately, with amazing and animated words and phrases and magic. His rhetoric was something I’d read of, but never heard before in person. I starting to wonder if I could do that. I also recalled the great preachers I’d heard and began to realize that my father was one of them. He had pathos. Then came the other lectures, from our tutors and guest philosophy and law professors. We learned the basics of ethical theories and political philosophy. The lectures were brilliant and exciting: I took notes in a way I’d never done before and wouldn’t repeat for a long time thereafter. I kept and treasured those notes for many years. Two blue legal pads. At first I didn’t dare to say a word when the lecturer would pose a question, but I always rehearsed an answer in my head. I was right! The big shots never answered the easy questions, they waited to ask questions of their own. I started thinking of questions to ask. Then objections. It just kept going. Soon I was tangling with the big shots at the coffee shop. We all received a small paperback library of primary philosophical texts, the classics from Plato to Rawls, each with an introduction and tips on how to convert the ideas into debate fuel. I read them every night till I had to start preparing my debate cases for practice rounds and the tournament. I did well. Before leaving I went to the college bookstore and bought four books: the Penguin Dictionary of Philosophy, the Oxford Companion to Mill, Rousseau’s Social Contract, and a compendium on political philosophy. My money was all spent and my mom picked me up. We listened to Cat Stevens on the way home. I felt like she understood that I left that place a different man, headed in, perhaps, a different direction. My doctoral advisor was shocked at my upbringing and my ignorance of academic pedigree and decorum and who’s who and where’s where and whatnot. My first year we rode the bus together—he hated to fly—to Chicago for a regional conference. On the second day we went to the University of Chicago, to see the campus, walk the halls, and witness the Lab School, founded by John Dewey, the misfortunate patron saint of Philosophy of Education. It was a damp, grey day. The gothic architecture stood with dignity and self-importance and the halls seemed electric with ideas and smarts. I wept, reverently. I’d at least heard of Georgetown, but Chicago was just a big city to me. I never knew such a place existed. My advisor didn’t help. “You could have gone here, Sam, I’m sure of it; maybe someday you’ll teach here. Wouldn’t that be something? Let’s go find a bookstore.” We made our way to a perfect used bookstore where I bought a rare early edition of William James’ Human Immortality for five dollars. I read it on the train ride back to our hotel. The book was engrossing and reading it afforded me the privacy to try and process some of what I’d just experienced. Now I was sure of it: I would become a professor. I would work retroactively to redeem myself and make-up for lost time and opportunity. I watched the last lecture of Fr. James Schall about a month ago. The Final Gladness. This time I understood exactly what Georgetown was, but I also had lost much of my former romance with the academy. I was becoming cynical and unhappy. Insecure, too. The light in my eyes was dying. I was losing my vocation, or something like that. Doubting it, like I’d always doubted , and ultimately rejected, the idea that I was born to wear a Roman collar. Schall’s somewhat boringly erudite, but rich and soothing, lecture showed me a man who spoke as a professor first and foremost. A person professing. Was that it? Was that the priest I was destined to be? Might I be graced with the chance to be a husband and a father and a “professor”—a secular priest of sorts? A man like my father? I don’t know what a vocation is. Even after all these years and diocesan posters and pressure I don’t understand it one bit. I understand its etymology, vocare: a calling, but that’s about it. This thing we call “vocation” is, for me, still a total mystery. The call is as absent to me as the One who calls. I still don’t know what I want to do or who I want to be when I grow up. Maybe a writer? A musician? I am a professor now, today, even though it is out of fashion for professors to profess these days. And when will I be “grown up”? When I’m dead? These are sentimental and silly questions, juvenile and flighty aspirations, but they are the roots and spirit of the stories I’ve recalled and shared nonetheless. A cubicle is a just a workplace. Like the one I sit in now. I have a very nice desk, a writing desk. Simple, but simply perfect for the time being.