A few days ago I asked the question, “Why do Christians tell crappy stories?”

I think part of the answer is that we’re afraid of living in the middle. So we avoid talking about the tension, the unresolved narratives, the days or months or years of it takes for faith to become sight.

I think another part of the answer is that we’re afraid of living in the mess. We’ve developed an aversion to gritty stories and messy situations and unpleasant scenarios — especially in art. Music is supposed to have “clean” lyrics, portrait subjects are to be fully clothed and movies must be rated G.

Why?

Certainly, there’s a level of age-appropriateness that’s valid no matter what your religious beliefs are. Christian or not, most parents try to introduce realities of the world to their children gradually, waiting until the child is developmentally able to handle the new information.

But beyond that, why have conservative Christians come to believe that everything they see and read and sing has to be sterilized of reality?

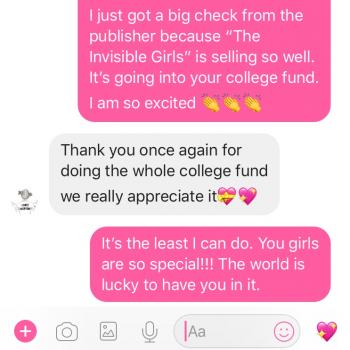

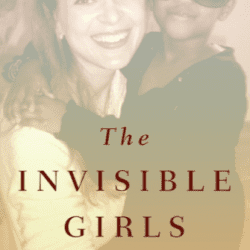

A few years ago, when The Invisible Girls published, I was scheduled to have a radio interview with a major Christian station. A few minutes before we were to go on air, the producer called me and said the host had decided to cancel the interview because they read the book the night before and discovered that there were three swear words in it — three four-letter words in 282 pages. (And they were quotes from other people who said them — like my atheist friend Libby who was dying of metastatic cancer at age 39. I think something would’ve been wrong if she didn’t swear.)

Because of three words in 282 pages, they cancelled the opportunity for me to tell tens of thousands of people the story of five irrepressible Somali refugee girls whose love brought me back to life after I’d almost died of breast cancer.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” I said when I’d hung up the phone. And then I opened my laptop and pounded my frustration out in this blog, In Defense of Profanity.

Because here’s the thing. If the Bible, the teachings by which Christians claim to have arrived at these decency standards, was made into a movie, what would the Motion Picture Association of America rate that movie? It would be too graphic for even an R rating. Maybe it could try for NC-17.

Christians will even relay these Bible stories to three-year-olds in Sunday School classrooms. David’s affair with Bathsheba and subsequent plot to murder her husband Uriah. Cain murdering Abel. The beheading of John the Baptist. The brutal torture and killing of Jesus.

When they’re a little older, maybe five or six, they get to hear of Noah passing out naked because he was so drunk. And Onan, killed for “spilling his seed” (aka pulling out instead of impregnating his sister-in-law). And Tamar, who was raped by her half-brother.

The Bible is a collection of messy, gritty and sometimes obscene stories.

And the God who shows up to redeem it all is that much more amazing — because God is not a fairytale godparent who shows up to redeem a G-rated Disney story. God is a fierce, relentless hero who redeems NC-17 hearts, transforms murderers into people who generously love their neighbors, compels cheating spouses to become faithful, and brings crucified love back to life.

The same is true for the world we live in now.

When we only read and write G-rated stories, we miss out on the depth at which the world is suffering, and the lengths to which God goes to redeem it. We become irrelevant to our non-Christian neighbors because we’re clearly living in denial.

When we only make or watch G-rated movies, we refuse to acknowledge reality as it is. When we decline to experience great grit, we miss out on the vicarious experience of even greater grace.

When we only listen to sappy, subpar songs that get wrapped up neatly in a bow three minutes later, we deny the common human realities of longing and disappointment and fear.

Of course, we don’t need to live on the dark side of the moon all the time. We don’t need incessant stories of illicit passion and crime. We do need the redemption, the long-awaited reunions, the repentance, the restorations that are just as true.

But unless and until we acknowledge the darkness, we can’t fully appreciate the light. After all, every shadow is a reminder that somewhere, sunlight exists.

And it seems like it goes without saying (but I’ll say it anyway) that the stories of darkness are descriptive, not prescriptive. Just because David murders Uriah doesn’t mean you should, too.

But we can’t appreciate David’s wonder of the God who kept all his tears in bottle unless we know the depth of his guilt and shame for what he’d done. We can’t appreciate David’s longing for God like a deer panting for water unless we know how far away God felt to his murderous heart. We can’t appreciate David’s cry for God to create in him a clean heart until we know how deceptive and dark his heart really was.

If God doesn’t tell G-rated stories, why should we?

And if we do continue to demand sterilized art and literature and music, what does that say about us?

What does that say about God?