Connor Wood

In today’s culture wars, religion plays a major role. And in the United States, it often seems to fall on the conservative side of the spectrum. For example, you hardly ever see rowdy hordes of secularists protesting against immigrants or gays, do you? Decades of research has confirmed that religion is correlated with mistrust of outsiders, sexual minorities, and other common targets of prejudice. But why? A new research paper has a fascinating, if unsettling, answer: conservative religiosity is partly an expression of our bodies’ need to protect against disease and germs – and throughout history, nothing has been a bigger source of new diseases than outsiders.

For their study, the paper’s authors, psychologists John Terrizi, Natalie Shook, and Larry Ventis, drew from a growing body of research on what’s called the “behavioral immune system.” The behavioral immune system isn’t part of the traditional physiological immune system – it doesn’t use white blood cells or attack pathogens directly. Instead, the behavioral immune system is a set of habits and behavioral responses that work to prevent nasty germs from entering our bodies in the first place.

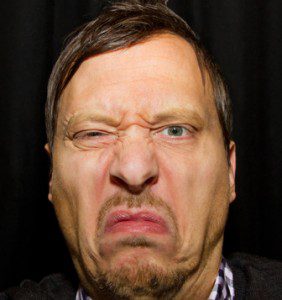

The disgust response is a perfect example of this effect. Shared by people of all cultures, the disgust response is an automatic reaction to really gross things – say, the sight of fuzzy green mold on food you’re just about to bite into. When we see, smell, or touch something gross like this, we make a characteristic face, which features a curled-up mouth and a wrinkled nose (see the photo accompanying this article). Interestingly, we also usually accompany this expression with an exhalation of air – including a disgusted “eech” noise (or something similar; your personal disgust noise may vary). Part of the cumulative result of this multi-layered disgust response is to effectively seal off our airways and our mouth, preventing any icky germs from getting in via the two most common pathways into the human body. (This function is hinted at in the Latin roots of the word: dis- means “bad” or “difficult,” while gust– refers to acts of eating. So, literally, “disgusting” means “something you really don’t want to eat.”)

Researchers have postulated that other elements of the behavioral immune system may include cultural behaviors. These could include preferring to hang out with members of one’s own group compared with people from other tribes or groups, since historically members of unfamiliar tribes would have carried new germs. It takes generations to build up immunities to specific pathogens, and so contact with a new tribe that carries bugs from a different region could often be deadly. The behavioral immune system helps to stave off this kind of threat by encouraging people to stick to their own kind.

Interestingly, a corroboration of this theory was found in 2009 by a group of researchers who discovered that, worldwide, the levels of infectious disease in any given country predicts the dominance of social conservatism in that country. Since one of the most important characteristics of social conservatism in any culture is a preference for ingroup members over outgroup members, conservatism may actually be an adaptive strategy in any part of the world where there are lots of germs, parasites, and pathogens that can be easily transmitted from person to person. After all, if you’re not hanging out with strangers, you’re probably not going to catch their bugs.

A final component of the behavioral immune system is conservative attitudes toward sex. Of course, sex is partly a perfectly natural way for people to relate, express affection, and produce children. But sex also involves bodies, and it involves them in a particularly intimate way that provides almost perfect opportunities for pathogens to cross over from person to person. Abiding by a culture’s or a religion’s strict rules about whom to have sex with and when is one way to mitigate the chances of exposing oneself, and by extension one’s group, to diseases through sex. This may (partly) explain why many social conservatives express outright disgust for homosexual activity or other forms of nontraditional sex – in one sense, their bodies are actually responding protectively to a situation they associate unconsciously with impurity and, in a deep-rooted way, disease and danger.

Inspired by this growing body of research, Terrizi, Shook, and Ventis hypothesized that religious conservatism would be associated with disgust sensitivity, fear of contamination, and prejudice against sexual minorities. In one study, they surveyed a fairly homogenous group of undergraduates at the College of William and Mary in Virginia, and found that religious conservatism was associated with both sexual and pathogen disgust, as well as with prejudice against gay people. In statistical analyses, the researchers found that religious conservatism mediated the relationship between disgust sensitivity and anti-gay prejudice. In other words, disgust sensitivity predicted religious conservatism, which in turn predicted negative attitudes toward gay people. This set of relationships bolstered the their hypothesis that the disgust response encourages conservative social structures and institutions, which in turn prompt people to mistrust outsiders and people who don’t fit cultural norms.

In the second study, a more diverse group of students from West Virginia University demonstrated a strong correlation between disgust sensitivity, fear of contamination, and prejudice against bisexual people. And again, high disgust responses predicted religious conservatism, which in turn predicted anti-bisexual sentiment – not the other way around. That is, religious conservatism didn’t predict disgust, which then predicted prejudice. The chain of relationships seemed to begin with sensitive disgust responses. Terrizi, Shook, and Ventis took their results to imply that conservative religious commitment may be just as much, or more, about literal, physical cleanliness and purity as about symbolic cleanliness. In their words, “religion may be in part an evolutionarily evoked disease-avoidance strategy that reduces potential contamination from out-group members.”

Now, that’s a fascinating but a loaded statement. It’s very important to point out that, as always, there’s a lot more to religion than just one single facet. Whatever religion is, it’s not just a disease-avoidance strategy. It’s also about ritual, group bonding, connecting with spiritual forces, and finding existential comfort in the face of life’s challenges and hardships. But even as religious commitment helps fulfill all those functions, the evidence is increasingly suggesting that it also has historically served as a kind of protective membrane around small-group cultures, keeping bad influences out. This strategy may seem backward and even morally wrong to modern members of liberal, Western cultures, which encourage openness to difference. But life hasn’t always been like it is today in Europe and North America; for much of history, and in many parts of the world today, contact with people different from one’s own group could be the beginning of a plague, a war, or even a genocide.

What this research encourages us to do is be humble about our own nature as soft, vulnerable animals in a world that often isn’t friendly. It’s not surprising that human traditions would have developed to keep us safe from danger – and thus, in many cases, prejudiced against outsiders. Yes, this legacy creates friction in today’s world, where sexual norms are changing and openness to people from other cultures is often an important asset. But it seems that the best way to negotiate that tension is to learn where it comes from and how we can work with what we’ve got. This requires being willing to not judge anyone – gay people, religious conservatives, or anyone else. If we’re creative and humble, we might be able to make religion’s difficult legacy work for us, rather than the other way around.