Connor Wood

Religious experiences get described in a lot of ways. People gushingly talk about a profound sense of oneness, about incredible bliss, joy, and ineffable meaning. One thing you almost never hear, however, is that a religious experience made someone more greedy and selfish. No one ever says, “Hey, you know what? I just experienced ultimate spiritual bliss, and boy, did it ever make me focus neurotically on my own struggles, financial problems, and dating insecurities!” Why this incompatibility between spirituality and self-absorption? A team of researchers from the University of Missouri thinks that the reason might be found in the brain, where reduced function in the region associated with self-awareness is correlated with greater spirituality.

The team, led by Brick Johnstone and Angela Bodling of the University of Missouri’s Department of Health Psychology, was familiar with previous research showing that suppression of the right parietal cortex appeared to inspire religious experiences. The right parietal cortex (or right parietal lobe) is a part of the brain found near the rear and top of your skull. It’s responsible for orienting the body in space and time, largely by keeping tabs on spatial and temporal relationships with nearby reference points. Neuroscientists such as Andrew Newberg of the University of Pennsylvania have previously found that long-term meditators and religious experts have reduced function in the parietal lobe during meditation or other religious exercise, leading many scholars to suspect that meditation dampens one’s sense of a separate self by reducing the ability of the brain to locate the body in relation to the surrounding world.

But much of this previous research was exploratory rather than hypothesis-driven in nature. What’s more, nearly all previous studies suffered from unsophisticated, one-dimensional measurements of spirituality or religiousness. Johnstone, Bodling, and their colleagues aimed to correct these shortcomings by articulating concrete, theory-driven hypotheses at the outset of their study, and by utilizing several different measures of spirituality. These measures assumed that spirituality is a multidimensional construct – that is, just as a person might be fiscally conservative but socially liberal, someone could measure as high in one form of spirituality, such as a sense of meaning in life, but low in another, such as frequency of private prayer. This more responsive and multifaceted way of thinking about spirituality promised to deliver a more intricate picture of the relationship between brain functioning and spiritual experience.

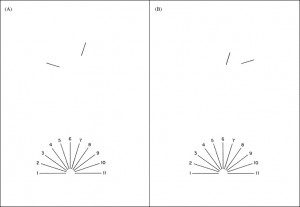

The researchers asked 20 different traumatic brain injury patients to perform a series of cognitive functioning tests that tell clinicians which regions of the brain are not functioning properly. For instance, a test of right parietal functioning asks subjects to match the relative angles of a series of lines (see the figure at right). Patients with high-functioning right parietal cortices can accurately indicate which angles match with the lines, but those with damaged parietal lobes have difficulties assessing spatial relationships and perform poorly on the task.

The researchers asked 20 different traumatic brain injury patients to perform a series of cognitive functioning tests that tell clinicians which regions of the brain are not functioning properly. For instance, a test of right parietal functioning asks subjects to match the relative angles of a series of lines (see the figure at right). Patients with high-functioning right parietal cortices can accurately indicate which angles match with the lines, but those with damaged parietal lobes have difficulties assessing spatial relationships and perform poorly on the task.

Unlike many neuroscientists who study religious experience, then, the University of Missouri researchers relied on clinical and behavioral data rather than direct brain imaging. This was intentional – while MRIs and CAT scans can tell you which parts of the brain are active at which times, tests that measure cognitive abilities can give a more reliable picture of the brain’s actual functioning. This behavioral data reduces uncertainty when it comes to pinning specific spiritual phenomena to underlying neural processes.

The researchers hypothesized that brain-injury patients who performed poorly on the tests of right parietal functioning would also report higher levels of different types of spirituality. They also predicted that strong performance on tests of frontal lobe functioning, which require subjects to trace a series of numbers and letters in a maze-like patterns, would be positively associated with spirituality. Tasks that tested functioning in other areas of the brain, such as the right and left temporal lobes, were not expected to be associated with spirituality one way or the other.

While the subject pool was small, the results more than supported the researchers’ hypotheses. Poor performance on right-parietal tasks was positively and significantly associated with spirituality as defined by the 5-dimensional “Inspirit” measure of spirituality, while strong frontal cortex functioning positively predicted private religious practice, such as personal prayer or meditation. Tests of brain function in other lobes didn’t predict spirituality at all.

However, while attenuated right parietal function did predict increased spirituality, it only achieved statistical significance for one of the Inspirit measure’s five dimensions of spirituality: forgiveness. The statistically significant negative correlation between the Inspirit as a whole and right parietal function depended largely on this single dimension of spirituality. In other words, people whose right parietal lobes didn’t work very well – most likely due to serious injury or illness – seemed to have a much easier time forgiving others than average people did.

Of course, one might question whether “forgiveness” really qualifies as a dimension of spirituality. After all, plenty of people who do not consider themselves “spiritual” or religious in any way forgive others around them on a daily basis. (Think about it: if this weren’t true, no atheists would ever be able to maintain marriages or have kids!) So does this research merely show that reduced right parietal functioning makes it easier to forgive others, without telling us anything about spirituality? Maybe not. Three other dimensions of spirituality – daily spiritual experiences, spiritual values and beliefs, and spiritual coping – were also negatively correlated with right parietal function. These relationships didn’t quite attain statistical significance, but together they contributed to the strong negative correlation between parietal function and spirituality. It’s likely that, in a larger sample, each of these dimensions of spirituality would attain significance.

Meanwhile, people who performed strongly on the test of frontal cortex functioning were much more likely than average to report regularly partaking in private religious practices. The frontal cortex is associated with what’s called executive cognitive function – the ability to direct attention, focus one’s awareness, and filter out distractor stimuli in order to concentrate. Thus, participants who prayed often in private – but not necessarily in public settings such as churches – appeared to have greater ability to focus on tasks and ignore distractions. This relationship makes it difficult to argue, as some might be tempted to do, that spirituality is simply the product of an atrophied brain. Counterintuitively, spirituality seems to be associated with enhanced function in some parts of the brain and reduced function in others.

This study is noteworthy because its authors made and corroborated specific hypotheses linking brain function to spirituality. The implications are clear: a reduced ability to orient one’s body in spatial and temporal relationships appears to be associated with greater spirituality – particularly, in this study, the ability to forgive others. The fact that all the measures of spirituality in this study were self-reports notwithstanding, these results are compelling because they’re theory-driven. If you have a data-based idea of how something works, and you come up with a concrete hypothesis based on that idea, even tenuous test results that match your hypothesis tend to support your underlying idea. The body is where our selves, our egos, are located. A brain that can’t tell where the body is in space and time apparently can’t produce a very robust sense of self – opening the gates to a kind of transcendence.