Nicholas C. DiDonato

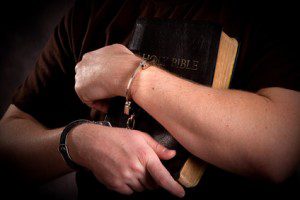

Redemption stories are the stuff of movie magic: a hardened criminal goes to jail, has a religious conversion, and then turns his life around and becomes a force for good. While this makes for compelling drama, it does not make for an accurate description of criminals’ actual appropriation of religion. Research by criminologists Volkan Topalli, Timothy Brezina, and Mindy Bernhardt (all Georgetown State University) suggests that “[t]hrough purposeful distortion or genuine ignorance” criminals take advantage of religious beliefs in order to justify their ongoing criminal behavior.

The researchers had noticed a rather odd finding in the field of criminology: on the one hand, criminals tend to have a problem with delayed gratification, but, on the other hand, most have strong religious beliefs. Religions often emphasize the afterlife and the consequences of evil deeds, and so the researchers puzzled over how the same group of people could accept the long-term consequences of their actions in the afterlife, and yet at the same time fail to take seriously the long-term consequences of their actions in this life.

To investigate this problem, the criminologists surveyed and interviewed 48 serious street offenders in the Atlanta area. Of the 48 criminals, 45 expressed religious conviction. Through interviews, the authors hoped to figure out how criminals reconciled their short-term thinking (crime) with their long-term beliefs (religion).

As it turns out, the criminals did so rather easily. As the researchers put it, “…the hardcore offenders we interviewed are able to exploit the absolvitory tenets of religious doctrine, neutralizing their fear of death to not only allow but encourage offending.” That is, the criminals relied on the fact that their religion (overwhelmingly Christianity) uplifts forgiveness and absolution, and so the criminals reasoned they would be forgiven too.

For instance, one thief, whose street name is “Young Stunna,” explained that Jesus would forgive him of his crimes: “See, if I go and rob a [censored], then I’m still going to Heaven because, umm, it’s like Jesus knows I ain’t have no choice, you know? He know [sic] I got a decent heart. He know [sic] I’m stuck in the ‘hood and just doing what I gotta do to survive.” Another criminal, “Detroit,” when confronted with the possibility of going to hell for his crimes, responded: “There is a Heaven and there is a Hell, but I believe that it is Hell on earth, and we [are] trying to fight to get [to Heaven]. … We [are] already in Hell, you know?” This notion of hell on earth resonated even with the murderer known as “Triggerman”: “No, no, no, I don’t think that [punishing murder with hell] is right. Anything can be forgiven. We live in Hell now and you can do anything in Hell. … God has to forgive everyone, even if they don’t believe in him.”

“Triggerman” not only denies that murder leads to hell, but even justifies his behavior because earth is hell and …you can do anything in Hell. Other criminals also justified their crimes with religion. The criminal called “Cool” makes sure to pray before committing a crime so that he can “stay cool with Jesus.” More than that, for some of his crimes, “Cool” sees himself as an agent of Jesus: “…if you [are] doing some wrong to another bad person, like if I go rob a dope dealer or a molester or something, then it don’t [sic] count against me because it’s like I’m giving punishment to them for Jesus. That’s God’s will. Oh you molested some kids? Well now I’m [God] sending Cool over your house to get your [censored].”

The authors are quick to note that religion does not necessarily justify crime, but that “[t]hrough purposeful distortion or genuine ignorance” criminals think of creative ways to “exploit” religion to their own ends. Of course, genuinely not knowing one’s own religion extends well beyond criminals, and the same goes for exploiting religion for personal ends. Even if the criminals purposely distort their religion’s teachings, the authors conclude that such religious rationalizations still may very well “…play a criminogenic role in their decision making.”

Obviously, this research does not negate the possibility that religion can be a force that helps to redeem or rehabilitate a criminal. That said, this research does suggest that how religion does this is far from simple. Clearly, merely having religious belief does not discourage criminal behavior for the criminals interviewed here — and as seen, for some, religious belief actually justifies their behavior. It seems that what religious conversion needs to do in order to rehabilitate criminals is to habituate them in the ways of religious practice — loving thy neighbor. Undoubtedly, some criminals would still manage to reconcile loving their neighbor with their violent crimes, but at least their treatment of religion would be less criminal.

For more, see “With God on my side: The paradoxical relationship between religious belief and criminality among hardcore street offenders” in the journal Theoretical Criminology, and also “New Study Suggests Religion May Help Criminals Justify Their Crimes.”