Connor Wood

I haven’t written a post here for more than a week. This is because I have been spending all my free time, and much of my non-free time, furiously writing two articles for an encyclopedia on spirit possession. Yes – you heard that right. Possession. By spirits. The two articles (which were technically due back on, um, January 1st) are about the zar possession cult in northeast Africa and shamanism in Korea, respectively. I wrote my master’s thesis on Korean shamanism, and have had an academic and personal interest in such things ever since. But where does something as wild and spooky as spirit possession fit into religion?

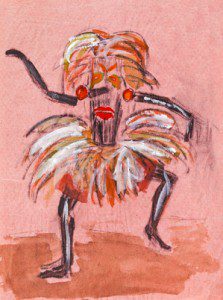

First, let’s be clear about what we mean when we say “spirit possession.” In the zar cults of northeast Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, many people (nearly always women) take part in ecstatic, music-intensive ceremonies that last all night and give a number of spirits, or djinn, the chance to intentionally take possession of their very bodies. It works like this: the women go into a trance while dancing to the clamorous drums, and while they’re checked out, the spirits check in. The spirits cause the women’s bodies to move and talk in strange, foreign ways, dance in wild rhythms, and express sadnesses and pains or cravings. At the end of the night, an animal is usually sacrificed, and the next day everyone goes back to their regular lives – no longer possessed.

Similar sights can be seen all over the world. The Brazilian religion Candomblé, Haitian Vodou, and Siberian Tungus shamanism – from where we get the English word “shaman” – all feature expert practitioners intentionally opening up their bodies to inhabitation by non-human spirits. So does Korean shamanism, which is also female-dominated. Meanwhile, the historical Christian, Muslim, and Buddhist literatures are rife with accounts of demons, spirits, and djinns taking hold of people’s bodies or minds and controlling or influencing them. This is clearly a major feature of world cultures, regardless of how bizarre or crazy we Western observers might think it is.

Because spirit possession turns up so regularly in human societies across the globe, I think we have a responsibility to take it seriously and study it. Why on earth would something like this happen so frequently? What is it about human cognitive or physiological architecture that allows us, even encourages us, to feel as though we’re being taken hold of by outside forces that are different from us, that are somehow completely alien – yet capable of inhabiting us so intimately? This is a very, very interesting question.

You wouldn’t necessarily get this impression reading through the literature in religious studies or the scientific study of religion, though. As far as many scholars of religion are concerned, spirit possession and ecstatic spiritual practices like the zar cult are peripheral sideshows to the real main course of formal religious practice and sacred texts. For the most part, the only folks who really take spirit possession seriously are anthropologists – because, having actually spent large chunks of their lives hanging out with people who are not middle-class Westerners, they understand that possession and related phenomena are basic features of human existence.

The scientific study of religion also neglects spirit possession. Today, the scientific study of religion is dominated by a few basic research strands. The first of these strands, and the largest, uses the tools of social science – such as surveys, demographic analysis, and so forth – to study things like waxing and waning of American congregations or the health effects of being a faithful churchgoer. Another strand is the study of how religions grew and evolved in human history, and what roles they play in human groups. This is the line of research I spend the most time on, and the one I think has the best connection with evolutionary literature. A third strand, smaller but more focused than the others, is the cognitive science of religion, which asks how human brains give rise to abstract concepts like “gods” or “heaven.”

The astounding prevalence of spirit possession cults around the world, however, makes me think that this is not necessarily the most important question we could be asking. Cognitive scientists of religion want to know how it is that human brains give rise to the sorts of processing errors that make us believe there are such things as invisible gods or incorporeal spirits. Their approach is highly focused on information and cognition and abstract concepts.

For example, one of the most well-accepted theories in the cognitive science of religion is one I’ve written about here recently: namely, the suggestion that religion arises from the overuse of anthropomorphic cognitive programs. Our brains are hardwired to be good at dealing with other humans; a couple hundred millennia of evolution has soldered those connections deeply into our neural circuitry. A lot of evidence suggests that, because our minds are so shaped by our hyper-social evolutionary history, we’re primed to see human-like agency and intentionality in all sorts of supposedly random natural phenomena, like faces in the clouds or the shapes of leaves in the wind. Our minds, then, are preprogrammed to intuit invisible human-like agents everywhere, and to believe in gods.

But here’s the thing: the gods and spirits people encounter in spirit possession cults aren’t abstract or invisible. They take hold of people’s bodies and make them do incredible, fantastic, or dangerous things. They make themselves apparent and act in ways that are recognizable regardless of which individuals they take possession of. This, then, is not people erroneously seeing patterns in randomness, or squinting to see faces in the sky. This is flesh-and-blood people being confronted with living, alien others who intrude into humans’ bodies and bring with them spirit wisdom, difficulties, or healing.

I’m not arguing that you should believe in the objective reality of these spirits, although you certainly can if you want. What I am arguing is that these possession experiences are not easily explained by citing mere cognitive processes. The idea that religion arises from a cognitive error – our tendency to over-intuit agency in our environment – doesn’t do justice to the strangeness that is spiritual possession. And this strangeness is so ubiquitous across human cultures that, clearly, there’s something here to understand. The explanations for it are going to have to be more rigorous and multifaceted than most of the theories that currently dominate the scientific study of religion. And they’re going to have to rely on more than just cognitive misfirings.

It’s also important to realize that spirit possession isn’t even so alien in our own, Western world. The bedrock writings of Christianity, including the church fathers and the writings of the desert monks of the early centuries C.E., are chock-full of stories of spiritual possession. What we think of as the Seven Deadly Sins, for example, were originally demons – that is, distinct, spiritual beings that intruded into meditating monks’ minds from the outside and tempted them. These demons were also known, interestingly, as logismoi, or “thoughts.” But what’s fascinating is that these “thoughts” were seen as coming from the outside – they were beings who could take over a person’s mind and body if that person wasn’t careful.

Today, spirit possession doesn’t have much cachet among the educated ranks of Western societies, or among, say, mainline Protestants. But the demons haven’t gone away. Demonic possession, especially of a low-grade, non-dramatic style, is a common trope among charismatic American Christians, who often describe sins and bad habits as the work of outside beings. Meanwhile, Pentecostals and Charismatics alike experience the Holy Spirit coming into their bodies from the outside. These are experienced,bodily realities – not abstract propositional ones.

Anti-religion writers and cognitive scientists of religion alike tend to consider religion as if it were mostly sets of abstract, linguistically representable propositions, like “God exists” or “Jesus saves” or “the Flying Spaghetti Monster is real.” But spirit possession shows us that propositions don’t even come close to covering all the territory of religion. People in zar cults or leaders of Korean shamanic rituals don’t believe in spirits. They experience and embody them. If we really want to tackle the question of what religion is and why we humans have it, we have to look squarely at practices that don’t fit into our own, Western cultural schemas – because they do fit into almost everyone else’s.

______

Note – I’ve edited this post to correct the spelling of the word “Vodou” to match preferred standards.