A curious thing has happened over the past few decades in American higher education. The humanities and social sciences – disciplines such as history, cultural anthropology, and sociology – have gone from having a slight liberal tilt to being almost uniformly left-of-center, with the vast majority of professors and researchers in those fields self-identifying as very liberal or even radical. This ideological uniformity has strained relations between the academic world and conservatives, and some thinkers – such as the members of Heterodox Academy, an organization that advocates “viewpoint diversity” at universities and colleges – fear that it degrades the quality of scholarly research. But why are academics so often more liberal than average to begin with? And, more topically, why is this tendency reaching new heights in the early 21st century?

[Caveat and warning: I strongly value liberal beliefs and the moral concerns (e.g., challenging unjust social norms) that they come with. This post shouldn’t be taken as an argument that liberal ideologies are illegitimate or purely self-serving. I do, however, think there is something fishy going on with the ideological purification that we’re seeing in many fields, beyond just an understandable reaction against the ugliness of the Trump administration and other populist characters. This belief comes partly from the fact that the increasing liberalism among academics and many other educated professionals was already well underway long before 2016. This post is my best, hurried attempt to explore what I think that fishiness probably is. And it’s a long post. Get comfortable.]

Academic liberalism isn’t a new phenomenon, after all. The arch-conservative magazine editor William F. Buckley first made his name as the author of God and Man at Yale, a book criticizing what he saw as the liberal, irreligious convictions of his Ivy League professors in the 1950s. The anthropologist Mary Douglas – like Buckley, a conservative Catholic as well as a public intellectual – pointed out as early as the 1970s that academics and researchers need to move often to pursue their training and jobs, and that this enforced cosmopolitanism is part of the reason why academics are usually more liberal than working-class people.

But it isn’t only academics who are getting more liberal. This increased leftward tilt is actually happening across the entire educated, professional sector of society – that is, people who hold four-year college degrees. And people with graduate degrees have swung even further to the left. NPR reports that

In 1994, 7 percent of post-grads were ‘consistently liberal,’ and 1 percent of people with high school educations or less were – not much of a difference. Today, the gap is 25 points wide – 31 percent of people with post-grad educations are consistently liberal, compared with 5 percent of those with high school educations or less.

At the level of partisan commitments, college graduates in general have become much more closely aligned with the Democratic party over that same time period. So the whole professional class has, seemingly, gotten a lot more liberal while the rest of society has mostly stayed where it was.

As educated Americans have become more liberal and have identified more closely with the Democratic party, it’s no surprise that Democrats in general have shifted leftward on some key issues. Conservatives have gotten a more conservative, too, of course – especially in the economic sphere. But the most striking shifts on social policy have mostly been on the left side of the spectrum. For example, people who lean Democratic have gotten much, much more supportive of immigration – both legal and illegal – since the second Bush administration. If you look at the Pew chart below, you see that Democrats and Republicans mostly had similar levels of support for immigration each year since the mid-1990s, but starting in the mid-2000s, Democrats started diverging massively from Republicans. Now, nearly 40 percentage points separate the two parties. That’s a lot. And almost all the change has come from Democrats – the linear trend for Republicans between 1994 and 2018 is virtually horizontal. (That is, there’s no statistically significant change in overall Republican support for immigration between those years.)

Somehow, it doesn’t seem likely changes this extreme over the timeframe of only a single generation reflects a sudden moral quantum leap among the college-educated. It seems more likely that there are some unconscious identity processes going on. What are those processes?

Moral Foundations and Liberalism

I’ve written about Jonathan Haidt’s and Jesse Graham’s Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) here a lot. According to MFT, people vary in how much emphasis they lay on a set of five different, basic moral intuitions. Two of these intuitions – harm prevention and fairness – are what Haidt, Graham, and other researchers call the “individualizing” foundations. They have to do with protecting individuals from abuses and injustice. The other three foundations (respect for authority, in-group loyalty, and purity or sanctity) are the “binding” foundations. The binding foundations yoke individuals into symbolic collectives, limiting personal autonomy in favor of group identity.

Unsurprisingly, liberals tend to care much more about the individualizing foundations. They’re concerned with protecting individuals from harm, but not as much about upholding authority figures or being loyal to the in-group. Conservatives, meanwhile, tend to care about all five foundations equally.

This means that liberals are, in effect, much more concerned about personal autonomy and freedom than conservatives are. We can see this in the changing attitudes toward immigration in Democrats and Republicans. As professionals and Democrats have become more liberal, they’ve become less sympathetic to a core conservative value – protecting the literal boundaries of the in-group by restricting entrance to it – and much more concerned about the plight of individual persons who are trying to enter the U.S. (often because they’re fleeing from economic collapse or violence in their home countries). Thus, more liberal morals are more individualistic morals.

Working-Class Morals and Professional Morals Aren’t the Same

It’s been clear for a long time – at least since the 1940s – that working-class people tend to be more socially conservative than professionals. Some psychologists argue – not always in so many words – that this is because working-class people are less intelligent and less educated than professionals, and dumber and less educated people tend to be conservative. And indeed, there is a positive correlation between political liberalism and IQ.

But this explanation doesn’t take into account the fact that, besides being the product of innate personality and rational reflection, people’s moral and political outlooks are also partially – even substantially – a function of the social and economic environment they live in. Research in the “rice theory” of culture, which I recently discussed on this blog, is an example. People who live in communities where there’s a strong need to cooperate and coordinate tend to be more collectivistic and less individualistic. Collectivists, in turn, tend to be more accepting of and respectful toward authority and social hierarchy. Why? Because, for all its flaws, hierarchy is useful for coordinating people. You might have fifty talented construction workers on your job site, but without a foreman and a construction manager to coordinate them, they’re going to get diddly-squat done.

This fact explains why professionals – people with college and graduate degrees – tend to be much less deferential to authority and much more independent-minded than their working-class counterparts. Professional labor is often creative, brain-based, and relatively autonomous. One scholar of social class in Britain locates the basic difference between high- and low-status work in personal workday autonomy – that is, whether you get to decide which projects you work on, and in what order. Sure, professionals have to coordinate with each other, and they have bosses. There are layers of hierarchy in any big bureaucracy. It’s just that professional labor tends to involve a lot more individualized decision-making and independent problem-solving than, say, factory assembly or mining.

As a result, professionals and highly educated people not only tend to be more individualistic, but they need to be more individualistic. You really can’t be a good research biologist or marketing executive if you’re always looking for someone to tell you what to do. But that need for structure and clear authority in’t a problem for most working-class jobs. Working-class labor requires a lot of rules, deference to authority, and mastery of physical skills. The type of person who needs clarity about social rules and norms (or who needs “cognitive closure,” in the parlance of psychology) will often fit right in at an auto shop or in a primary production field like mining or logging. By contrast, professional labor requires (and rewards) relatively more autonomy, initiative, and flexibility. And this gap is only growing wider as the tech sector gobbles up a greater and greater percentage of the economy, incentivizing rule-breaking, “disruption,” and innovation.

Social Signaling and Elite Overproduction

Okay. So professionals – including academics, but also lawyers, journalists, tech workers, designers, and more – tend to be a bit more individualistic than their working-class counterparts, thanks to the practical pressures of their economic location. Working-class people tend to be more collectivistic thanks to their economic location. And moral worldviews – that is, whether you tend to emphasize all five moral foundations or only the individualizing ones – are a direct proxy for individualism/collectivism. My argument is that these relationships explain a big chunk of the difference in political values between the educated and the less-educated: liberalism is essentially the political outlook that goes along with, and legitimates, social individualism and autonomy.

Why, then, are the highly educated becoming more liberal, relative to the rest of the population? Why has the gap between working-class and educated moral outlooks grown into a chasm over the past generation?

The best candidate for an answer to this question, I think, is “elite overproduction,” in the terminology of historian and systems scientist Peter Turchin. Elite overproduction is what happens when there are too many well-qualified (read: university-educated, intelligent, well-traveled, etc.) young aspirants to high-status professions, but too few openings for membership in those professions. A prime example is the law school crunch that’s pinched young lawyers over the past decade. Until recently, a law degree and bar licensure was a virtual guarantee that you’d enjoy an excellent income and professional status. But now, there aren’t enough jobs to go around. Too many bright young professionals with law degrees, and too few openings in prestigious firms.

So competition increases. So does exclusivity. A job that once would have gone to a reasonably bright person with a law degree from a flagship state university now goes only to Harvard or Yale grads. The clerkship that previously was available to anyone with good law school grades now is out of reach for all except the most elite applicants (probably also from Harvard and Yale). The list of requirements to enter the elite grows longer and longer. The list of potential disqualifying traits grows longer too. So well-educated people feel desperate to secure their place on the fast-disappearing island of prosperity.

Elite overproduction is one of the major symptoms of a general rise in economic inequality. As society becomes more unequal and more pyramidal, the top levels of the pyramid get narrower and narrower. More people fall out of the middle class into the ranks below. Fewer people can make it into the comfortable top quintile, even if they have the right credentials and qualifications.

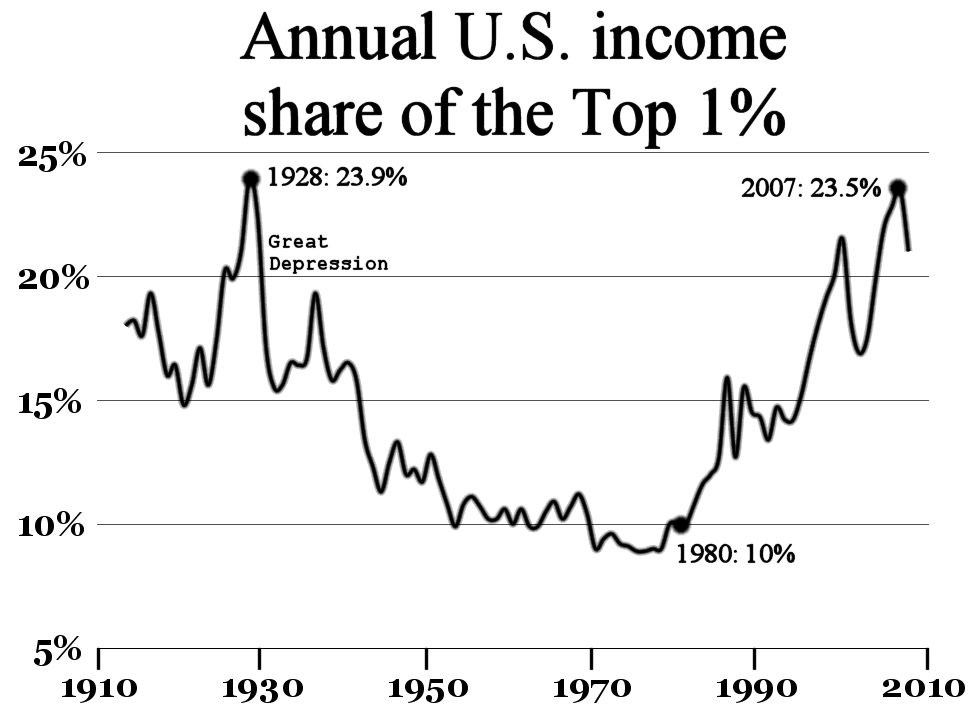

Now, we’re in an age of extraordinary economic inequality. This is a truism, but not many people know just how extreme the situation really is. A New York Times article last year presented a dynamic graph that showed the change in income growth by wealth percentile between 1980 and 2014. It’s shocking. The superrich are commanding extraordinary levels of income growth, while the less-fortunate are seeing their incomes grow much more slowly, or even – in the lowest decile – start to shrink. Another chart from economist Thomas Piketty’s data (below) shows that, since 1980, the percentage share of income taken home by the top 1% in the U.S. has reached levels only previously seen just before the Great Depression.

So in essence, members of the professional class have faced an increased pressure to signal that they belong to that class, thanks to elite overproduction. There are just too many qualified people with degrees from name-brand universities trying to compete for too few slots in the elite, so the elite has to find ways to screen out larger and larger numbers of aspiring members. This heightened screening leads to something like what sociologist Thorstein Veblen called “conspicuous consumption” – ways of advertising your belonging to the leisured, educated classes, so you’ll be accepted by the people who guard access to good jobs, mentorships, and connections.

What does this have to do with the increasingly strong liberalism that’s swept over the professional class? Well, one of the best ways to determine whether someone really belongs in the elite is to determine how much freedom he has – how liberated he is from autonomy-reducing, socially binding networks of family, religious, and community obligation. In short, when someone has a highly individualistic moral outlook, what that person is signaling is a certain level of independence from social relationships. She’s signaling that she can afford to flout norms, to not care what other people think, to emphasize the individualizing moral foundations over the binding ones. My point is that these things are luxuries. They’re something only a person with a fair amount of resources – finances, education, and status – can realistically hope to do.

From the perspective of the elite, people who think like working-class people – collectivistic, authoritarian, rule-oriented – don’t belong. People who are liberated to think independently, to explore the world adventurously from a secure footing, do.

This isn’t even as amoral as it might sound. For logistical and cultural reasons, people who are too bound up in localistic social ecologies really don’t always fit easily in a lot of elite professions. Say you’re the hiring manager for a multinational law firm. You’ve got two applicants between whom to choose, each with outstanding résumés and stellar recommendations. But one applicant is an active member of her local Catholic parish, lives near her grandmother and visits her several times a week, and grew up as a fourth-generation resident of the nearby countryside. Her life is filled with family and religion.

The other applicant – who has the exact same educational credentials, remember – is one of those types who couldn’t wait to leave her podunk hometown. She sees her family maybe twice a year. She’s got no religious convictions or community commitments to speak of. She lives by herself in a flat in the city.

The position you’re hiring for will involve extensive travel. It also comes with the strong likelihood of relocation with future promotions.

So, no matter how strong the first applicant’s credentials, the choice is a no-brainer: you pick the second applicant.

That is, you give the (prestigious, well-paid, career-launching) job to the highly qualified applicant with loose social ties and high levels of personal autonomy, not to the highly qualified applicant with dense social ties and lots of interpersonal obligations. All those extra obligations come with costs, after all. A junior partner who attends choir practice each Tuesday and babysits her niece every Thursday is one who can’t drop everything and fly off to Tokyo at short notice. But being able to drop everything and fly off to Tokyo at short notice is part of the job.

So, over the course of decades, people with strong community ties tend to get weeded out of the most prestigious professional occupations, because those occupations demand a level of flexibility and independence that just isn’t compatible with densely entwined community life. As this bifurcation proceeds, the semantic connection between social independence and socioeconomic status gets more and more solidified. The two come to be linked more tightly together in people’s minds. So, when you encounter someone who’s highly socially independent, you’re predisposed to unconsciously assign a higher likelihood to the proposition that this person is high-status.

What’s the best way to credibly signal this social independence? Well, it isn’t to go around telling people “I don’t have many binding social obligations weighing me down.” That would be far too explicit, and therefore vulnerable to manipulation. As the anthropologist Roy Rappaport pointed out, verbal language is easy to tell lies with, because there’s no intrinsic connection between the symbols used in language (that is, words) and the concepts they refer to. So if you want to believably communicate something about yourself, you need to look for non-verbal, difficult-to-fake ways to do so.

Example: you don’t convince anybody that you’re rich by telling everyone that your bank account is seven figures. Anybody could claim they have millions in the bank, even the homeless guy who’s always asking for cigarettes outside the Dunkin Donuts. No, you convince people you’re rich by owning a 4,000-square-foot mansion in West Cambridge and a pair of Lexuses. Because not everyone can do that.

In the same way, if you want people to know that you’re a genuine upper-middle-class denizen – free of excessive social ties and available for professional mobility – you have to demonstrate these things. You can’t just claim them. And the best way to demonstrate them is to show that you have traits that (a) are characteristic of the educated, professional class and (b) aren’t fully under conscious control.

Gut intuitions about morality are a perfect example.

Intuitionist psychologists point out that the cognitive operations that lead to moral and political preferences aren’t under anything like the amount of rational control that we like to think they are. They’re much more similar to – even based on – emotional responses, which are automatic and out of the control of the conscious mind. Because of this automaticity, emotions are thought to be relatively difficult to accurately mimic – think of the Duchenne smile versus a fake smile. We wrinkle our eyes when we’re genuinely happy. But when we’re just trying to mimic happiness, we only turn up the corners of our mouths and bare our teeth like apes trying to scare mating rivals.

And so the pressure is on: we need to signal that we have the all-important traits of high-status people, but we have to use signals that are several steps removed from practical life.

This, I think, is why the rhetoric around personal autonomy has gotten so virulent and non-negotiable among university students, and why it’s become so much more socially risky in educated circles to express opinions that emerge from the binding moral foundations. The pie is getting smaller. Only people who really have the resources – whether financial, social, educational, or otherwise – to live a life largely free from binding allegiance to authority, in-groups, or traditional purity rules can express the right moral commitments. And only people who fit this bill can get a slice of the pie. So savvy people start expressing more and more of the sentiments and moral convictions that get them the social rewards.

My contention is that this happens largely outside of explicit rational calculation; instead, it happens at a gut level. Without being fully aware that they’re pursuing a social strategy, people slightly exaggerate the beliefs and expressions of moral emotion that fit in with the morally individualizing, autonomy-valuing ethos of professional, educated groups. And they’re not really being disingenuous – they really do value personal autonomy and the individualizing moral foundations. They’re just playing them up for social advantage, unconsciously. (This is an example of the biologist Robert Trivers’s claim that individuals can best send manipulative signals if they fully believe the content of those signals themselves.)

But because the social dynamics within the professional world are extremely competitive and only getting more so, this social identity signaling – which we all do, all the time, and often to good effect – is turning into an arms race, as people try to elbow past one another to show who is really liberated from worrying about the well-being of the in-group: You think immigration is an unmitigated good, always and everywhere? Well, I think that national borders are fundamentally illegitimate, and anyone who defends national identity is a racist!

As a result, liberal and progressive beliefs – which, under normal circumstances, are vitally important to any nation or community, because they help shine the spotlight on injustice, elevate the concerns of outsiders, and push back against cultural stagnation – are becoming weaponized in certain small (but influential) sectors of society. This “purity spiral” is, in turn, creating a massive blowback effect. The majority of the population has some justifiably conservative instincts about, say, the need for some basic level of shared group identity. When they find that cultural leaders think that their worries about maintaining group identity not only unimportant, but actually morally repugnant, this creates a massive opening for populists to come striding in and whip up dangerous anti-intellectual and anti-elite sentiments. Which is happening all over the world.

The thing to remember is that the ultimate culprit for (at least most of) this purification and polarization among the highly educated is economic and social inequality, not liberal hypocrisy. Excessive inequality royally messes things up. In our day, it’s messing things up by distorting people’s moral and ideological beliefs to become signals of group identity – or, rather, the group identity we aspire to.