In recent years, there’s been a growing awareness of the human body as a microbiome. Bacteria not only perform vital functions in systems like digestion; they vastly outnumber our own cells, influence the way we think and feel, and raise questions about what it even means to be human.

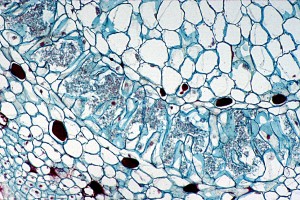

When I think of this discovery, I think of the Buddhist concept of Anatta, or “no-self”–the idea that there is no stable, identifiable self in the human mind. We experience our minds as unified and persistent phenomena, but in fact, they’re a complicated mosaic of parts “talking” to each other to create the illusion of a whole. This schema is mirrored in the human body: from a distance, it appears to be one thing, but once you get under the skin, you discover many interlocking parts coordinated in a system of almost unimaginable complexity.

For awhile now, I’ve been thinking about these ideas in relation to my understanding of deity. I’m not interested in joining the debate over whether gods are “real” or not, or how we’re “supposed” to work with them, or what they “want” from us. (In individual or intimate group practice these are profound questions; when we get upset and start fighting about them, though, they’re profoundly silly.) Instead, I’m interested in how diversity of practice actively creates the gods–or, at least, their presences within human civilization.

If you haven’t read Rhyd Wildermuth’s post on worlding the gods, do take a look. “It’s we who actually world [the gods] into the earth,” he writes, “and how we world them is dependent upon what we do, who we are, and the sort of world we create around us.” Furthermore:

The altar is a mirror. You’ve been the altar all along. The offerings which mattered most were not the pouring out of libations you could barely afford, but the actual act of offering at all. The candles lit upon the shrine to a goddess are lighting flames inside of you. You’re the wax, you’re the wick, you’re the flame for that goddess.

Yes, yes, yes.

Let’s imagine a god with only one devotee. That devotee might compose beautiful myths and hymns for that god. That devotee might create lavish altars and write a thousand pages of theology. But there’s only so much one mind can do.

Now imagine that another devotee joins the first. She takes the myths and hymns and, in her own expressions of love, changes some of the details based on what she hears when the god speaks. (Human eyes all perceive color a little differently; it should come as no surprise that our reception to divinity is variable, too.) She composes new myths and hymns. She disagrees with some of the first devotee’s theology. She places different objects on her altars. The god stretches, grows, evolves.

Now imagine a hundred devotees, or a thousand, or ten thousand, each with a slightly different conception of the god. Think of the progression of gods throughout human history, the way they shift and change, take on new names and meanings and shed old ones, simultaneously guiding and adapting to human history. Think of how the jealous and violent god of the Israelites became the compassionate, loving god of the majority of today’s Jews: over generations, we gradually worlded hir that way. Just as the human body has countless parts that work together to form a whole, the god’s body functions, here among us humans, through our acts.

This is why diversity of practice is so crucial for a god’s survival. I’ve never in my life encountered a healthy monoculture. A field of nothing but corn quickly succumbs to pests; a body made up of nothing but left feet isn’t going to live very long. In order to world our gods, we need disagreement. We need conflicting versions of the same stories. We need truths that might appear to us, with our limited human perception, as paradox. We need to be made uncomfortable from time to time.

Note, though, that embracing diverse practices doesn’t imply embracing an infinite variety of practices. Take violence, for example (as some of you were no doubt revving up to do in the comments section). If you belong to a pacifist sect for a god, and another sect is thoughtfully exploring that god’s warlike aspects–through martial arts, text study, or what have you–that’s healthy diversity, even if you don’t like it. Together, the two sects are putting together a composite image of a complex deity. But if the other sect takes up weapons and commits acts of violence in service to the god, then that part of the god’s body is unwell and must be healed.

Why do we need to world the gods at all? Well, arguably we don’t; the happiest nations in the world happen to be the least religious, and I’ve written before about walking away from gods. But those of us who do world them–who love them intimately or venerate them with awe or channel their power into service for our communities or all of the above–need to be aware that we can’t know them in their entirety. We only have one brain apiece, and one brain will never be enough to comprehend the divine.

So the next time you encounter someone with a different idea of a god than your own, take a breath and relax. It doesn’t necessarily mean you’re wrong. It likely means that you’re both cells in a colossal, thriving, numinous body, and you’re both doing your job.

Click here to follow Asa West on Facebook, and click here to book a tarot reading!