When my friend Amy converted to Catholicism ten years ago, she wrote me a letter confessing that she wasn’t yet sure of her belief, but that she wanted to “enter the story.” She recognized in the mass and the rhythm of the liturgical year that the Catholic church had established an imaginative framework big enough to hold the entire Christian story, which she encapsulated as “the story of how something unimaginably large and all encompassing is contained and revealed by a single life.”

We tell that story again and again, she wrote, in every single mass, and every year, and through every liturgical season. Catholics walk in a circle, not a line, and yet with each turn through the birth, growth, death, and resurrection of Christ, something more is revealed–about us, about God, about our relationships, about the human experience. Catholic liturgical tradition is a scaffold strong enough to hold eternity.

I’m a cradle Catholic and not the intellectual that Amy is, so while I found all this beautiful and poetic I didn’t really feel it. I’d never had any proper catechism–in religion class at my Catholic school in the 80s I remember mostly talking about the Marian apparitions in Medjugorje–but the mass, the liturgical feasts and fasts, the eucharist, all this was as natural to me as breath. I loved the Church as I loved my childhood home. It was a place of magic and mystery but also of comfort and familiarity. The mass appealed to me in an aesthetic way, because it smelled good, looked good, and sometimes, if you hit the right parish, it even sounded good (though that’s become increasingly rare).

But mostly, it was boring.

And yet, occasionally, maybe through stubborn repetition, I’d find myself transported, lifted out of the mundane, if just for a moment.

I think it was O’Connor who said that as a writer, you have to show up to work every day, even though usually nothing happens, because at least if you’re there you won’t miss it when it does. I’ve slaughtered that quote, whoever said it, but it’s a very Catholic thing to say. Something is always happening in the mass, a great miracle, every time, whether we apprehend it or not.

O’Connor also said–and this quote I verified–that “the meaning of a story should go on expanding for the reader the more he thinks about it, but meaning cannot be captured in an interpretation…Too much interpretation is certainly worse than too little, and where feeling for a story is absent, theory will not supply it.”

What I lacked in theory and interpretation I made up for with feeling. I loved the church. I had an emotional faith, not an intellectual faith, while Amy was the other way around. We needed each other. When we started writing each other the letters that became Love and Salt, it was out of fondness but also out of hunger. I wanted to know what she knew–apologetics, history, philosophy, theology. And she wanted to know what I knew, what the believer knows.

But it wasn’t any of the philosophy or theology she shared with me that really converted me to a love of the mass. It was Lord of the Rings.

I remember being surprised when Amy told me it was her favorite book. I associated Tolkien with teenaged nerds playing dungeons and dragons in their basements. The Peter Jackson adaptations had just come out, but with no background and no childhood attachment to the story, I sat there in the theater with my then-boyfriend, uncomprehending and distracted by the violence.

I was so far outside the Christian intellectual world I had no idea that Tolkien was as much its patron saint as O’Connor, or that his masterpiece was not only the pinnacle of fantasy but a major work of imaginative theology. When I finally read The Lord of the Rings, at Amy’s insistence, it prepared me to receive the symbols and parables of my faith as if they were new, and it opened my imagination to their depth and grandeur. I felt I’d finally begun to understand my faith life in its proper scale–small as a hobbit’s and yet no less significant. When I’m bored in mass now I imagine it as that great hall where the elves told their tales and sang their songs while some dozed. As ridiculous as that sounds, it’s not that far off. It is right that we should feel we’ve entered the hall of a king when we go to Mass, and that such humble creatures as we are, dirt under the nails and all, have been invited to a feast.

But I think even The Lord of the Rings wouldn’t have affected me so profoundly if I hadn’t been training as a catechist simultaneously. I’d enrolled in a program to lead the 3-6 year olds in our parish in the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, which teaches not with coloring sheets and crafting but as Jesus taught, in parables. It’s a program that believes in the power of entering the story. I spent two years praying with the parables and breaking them down to simple terms a toddler could grasp–literally touch: seeds, yeast, wine, oil, light (candles), dark (candle snuffer). When I finished, I was convinced that this kind of catechesis is what most parishes are missing–not for children, but for adults. Jesus knew what he was doing, and so did Tolkien. Most of us don’t need theology to aid our belief. We need fairy tales. We need to hear stories with the same elements in infinite arrangements until we know them by heart.

“Liturgies work affectively and aesthetically,” writes James K. A. Smith in his new book, You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit. “They grab hold of our guts through the power of image, story, and metaphor. That’s why the most powerful liturgies are attuned to our embodiment; they speak to our senses; they get under our skin.” Smith, a philosophy professor at Calvin College, isn’t Catholic, but he argues persuasively for the value of traditional liturgical worship. Liturgy, he writes, bends “the needle of our hearts,” and when liturgies are disordered (his term), our hearts bend the wrong way. He argues that traditional Christian worship re-orients our hearts toward eternity, while so much contemporary evangelical protestant worship simply apes popular culture, with churches designed to feel like secular spaces, arenas, malls and coffee shops. Such spaces do nothing to move our hearts toward eternity; they simply reinforce the habits we’ve trained in frequenting those spaces–habits of consumption. They encourage us to “worship” as we shop, based on novelty, innovation, self-expression, with the ultimate goal of a satisfying or affirming experience.

“Liturgies work affectively and aesthetically,” writes James K. A. Smith in his new book, You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit. “They grab hold of our guts through the power of image, story, and metaphor. That’s why the most powerful liturgies are attuned to our embodiment; they speak to our senses; they get under our skin.” Smith, a philosophy professor at Calvin College, isn’t Catholic, but he argues persuasively for the value of traditional liturgical worship. Liturgy, he writes, bends “the needle of our hearts,” and when liturgies are disordered (his term), our hearts bend the wrong way. He argues that traditional Christian worship re-orients our hearts toward eternity, while so much contemporary evangelical protestant worship simply apes popular culture, with churches designed to feel like secular spaces, arenas, malls and coffee shops. Such spaces do nothing to move our hearts toward eternity; they simply reinforce the habits we’ve trained in frequenting those spaces–habits of consumption. They encourage us to “worship” as we shop, based on novelty, innovation, self-expression, with the ultimate goal of a satisfying or affirming experience.

But this isn’t worship at all. It’s recreation.

Smith’s book is a fascinating exploration of what is drawing more Christians back to liturgical worship, and it deserves to be read by Catholics like me. I wouldn’t have realized, without Tolkien and a preschool catechism program, the way that the mass: “inscribes the [Biblical] story into our hearts as our erotic calibration, bending the needle of our loves toward Christ, our magnetic north. The Scriptures seep into us in a unique way in the intentional, communal rituals of worship…the Word is caught more than taught. The drama of redemption told in the Scriptures is enacted in worship in a way that makes it ‘sticky.’ Study and memorization are important, but there is a unique, imagination-forming power in the communal, repeated, and poetic cadences of historic Christian worship.”

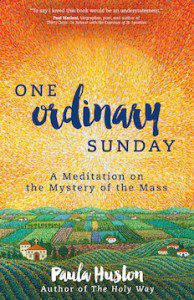

Like Smith, writer Paula Huston focuses on the significance of historical worship designed to reorient us toward the divine in her new book, One Ordinary Sunday. Huston’s book is a personal essay, structured as her experience of a single Mass on a real Sunday in a real parish. She unpacks the historical, theological, and emotional significance of each part of the mass, beginning with her ride to the church.

When she and her husband enter the sanctuary for mass, “we will step back nearly two thousand years to once again experience what cannot possibly be experienced without the bridge through time we call the Mass. Yet this is not the half of it. For the Mass is a living liturgy, pulsing with the present, pregnant with the future. Each time we participate, we enter a different dimension…kairos time…a suspended moment in which the chronological march of minutes suddenly seems to halt, allowing everything to happen at once. In this kairos moment of the Mass, we are healed and restored and spiritually fed. We are handed strong armor against evil. We are unified and made whole as people and a Church. And we are ushered into a new kind of life–one that participates in the divine.”

Huston also mentions Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, that program designed for preschoolers that taught me so much about the mass. Observing her own grandchildren in church, she notices their restlessness, distraction, and curiosity, “their eyes being caught by the light through the stained glass windows, by the flicker of the candles on the altar, by the golden gleam along the edges of the Book of the Gospels.” Huston sees in them “the phenomenology of the flesh. They are thoroughly experiencing their experience. There is no intellectual screen between them and what is unfolding before their eyes.” She wonders if this is what Christ meant when he said we must become like children–not demanding a satisfying experience or our own self expression, but observing, trusting, even resigning ourselves to sitting still for an hour in what might be complete boredom. Consenting to be, for that hour, an essential part of something much bigger than we are. Entering a story that is not yet over.