I’m seeing a healer. The woman works out of an office where she officially does something else, something totally unrelated to healthcare or spirituality, I’m not even sure what. I’m not even sure how I got here, except that a friend who goes to my church saw something in me that needed healing, and I didn’t argue. There’s so much in me that needs healing, and at this point I’d seek out a witch in a hut made of chicken bones if I thought she might help. My witch is a Christian lady in an office building.

I sit in a plush chair facing the window. She plays soft music. She reads scriptures and invokes Jesus as the Great Physician, which I find strangely, unexpectedly comforting, imagining Robert Powell with a stethoscope. She prays for me, because I can’t.

But the best part is this: she puts a hand on my back, between my shoulder blades, and the warmth of her touch radiates through my upper body. I imagine the heat from her palm penetrating my skin and reaching deep inside to my heart, which I imagine as the vintage holy card I love: fleshy and pierced by swords. Her hand is the Hamsa, an eye in her open palm, protective, soothing and seeing, looking deep inside for that black spot on my heart. I remember my mother saying she felt that kind of penetrating warmth from the hands of Dodie Osteen when she tried to get her faith healing from lung cancer. It’s not a miracle, really–it’s just human touch. But maybe that is a miracle after all. There is power in a woman’s touch–gentle, protective, maternal, and yes, healing. There’s a reason you always think we’re witches. Babies who aren’t held fail to thrive. Grown people who aren’t held suffer too–not just loneliness, but real physical depletion.

I like going to this woman because I like her touch. I like her kind, soft voice and her maternal ferocity. I like that she talks about demons like they’re real and God like he’s real and my pain like it’s real—she sees a connection between all three and even if I’m skeptical it’s a relief to spend time with someone who has it all figured out. It may or may not be a demon, but I’m desperate to cast something out of me, sure there is something, or yeah, maybe someone, that needs to go.

She tries to get me to name it. She asks probing questions. She commands whatever is plaguing me to identify itself.

I want to be careful how I talk about this, because I know it sounds crazy. Maybe there is no way to make it sound less crazy. Maybe I’m becoming a religious nut. Maybe I’ve always been a religious nut.

When so much of your life has felt like horror and pain, the language of demons and spiritual battle makes sense. My body, my soul has been at war most of my life. It is shredded, and I feel like a ghost, a specter. There has been no tender parent with the loving, warm hand to call me back to the earth, to ground me here, in what is real.

I wish I could say I have some sort of mystical visions in this woman’s office, or that I hear voices, or even that I go into convulsions while she casts out demons. But it hasn’t been like that at all. Sometimes I cry because it feels so good to have another woman care for me. Because her hands are warm and her voice is stern and powerful as she commands everything that plagues me to just leave me alone.

Last time she demanded the demons name themselves. I just sat there with my eyes closed, not realizing I was supposed to do the naming. I didn’t hear any demons talking to me, even when she commanded them to speak to me in the name of Jesus. While she spoke I imagined her standing before a steaming cauldron in robes. I liked the image.

Meanwhile I waited for the demons to speak to me, and when they didn’t, my metaphor-making brain switched on and tried a different tack. What is at the root of my suffering? What has driven me to make terrible choices? To trust the wrong people? To put my hope in the wrong things? To tolerate abuse and manipulation? What has been with me my whole life, given me a death wish, kept me awake at night, kept me from eating and exercising and being healthy? What has driven me to drink and take Xanax?

Does it matter if we call this source of pain a demon, or an emotion, or pathology, or a diagnosis? Isn’t it just a question of terminology, when the treatment turns out to be the same—healing touch, meditation or prayer, communion with the living? Whatever we name it, aren’t we all really talking about the same thing?

I finally decide I will say the word grief. And when I say it, it’s as if I exhale without exhaling. I fold up and lose strength. This is not the name I think she was hoping to hear. And it’s not the name I was hoping to say. I wanted to shout a demon name like Beetlejuice and see something materialize before me.

But then, she starts to talk to Grief directly.

Grief, are you the most powerful force in Jessica?

Grief, what lies do you tell her?

Grief, what do you ask her to do to satisfy you?

Grief, what do you prevent her from doing?

Grief, I command you, tell us your secrets and how you’re keeping Jessica captive.

***

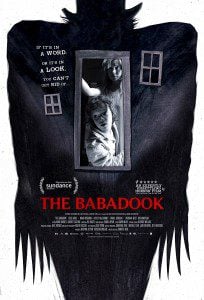

After the session my ears hurt and I’m dizzy and I go home to take a two-hour nap. “This is normal,” the healer tells me, as if some physical pain is to be expected when you battle with demons, but I think I’m just coming down with a sinus infection. When I wake up my friend Adam comes over to watch The Babadook. That’s all he wants for his birthday this year, he tells me, to watch The Babadook, and I feel like this is a gift I can give him.

The film begins with a nightmare: a pregnant woman and her husband are in a car crash on the way to the hospital to deliver their first child. Woman and son survive, father dies. It’s not a nightmare though, it’s a flashback. The mother wakes in her bed to hear her son calling for her, deep in his own nightmare.

The husband and father has died and Grief has moved in and made everyone crazy.

After seven years, Grief has grown so powerful he has taken on shape and form. He is a monster. He presents himself to the child first, who senses there is something in the house that will hurt him. This thing will take away his mother. Is taking her.

His mother’s grief is a threat, even more of a threat than his own bereavement. And he too is deeply grieving—grieving the father he never knew, and the family he never knew, and the mother he never knew because she was changed at the moment of his father’s death, which was also the day of his birth. Even his birthday is horrible for his mother. He knows that there is something in him she hates.

Oh, how I felt that in my guts–to know, as a child who needs, more than anything, protection and love, that you are a reminder of something too painful for your own parent to face. To know, or to think you know, that your own grief makes you scary and weird and unlovable, untouchable.

Most of the reviews of the film see Samuel, the child, as a test to the viewer’s compassion, because he is a scary, violent child who builds homemade weapons and says weird inappropriate things to strangers about his father’s death. They compare him to the scary children in The Omen and The Shining. He has violent seizures. He attacks another child when she comes too close to his pain: “You’re not good enough to have a father” she taunts, and he pushes her out of a treehouse, and while everyone else cringed I (silently) cheered. (Don’t worry, she only breaks her nose.)

But Grief isn’t always a horrible, demonic, ugly, and violent thing. Sometimes Grief is beautiful. In one scene Grief takes the form of the dead husband, flesh and blood, who can kiss and hold his mother and stroke her hair. He stands in the light of the basement, and the mother melts into him with relief and longing. That touch that she has longed for, protective and warm, comes back to her, and she can breathe again.

But then the husband asks for the boy, and she knows. This is Grief too, and this vision of a husband isn’t real. How she wishes he was real. But he’s not. She’s been seduced by a vision of what is lost and gone forever. She runs.

In other scenes, the mother tries to purge her pain. She literally pulls a tooth from her mouth that’s been worrying her throughout. In an appalling sequence, she tries to vomit it up, emitting a torrent of black bile that is the closest image I’ve ever seen to what long-term, complicated grief feels like—like hot, black poisonous tar gumming up the whole works. I have felt that urge to force it out. To cut myself from sternum to pelvis and let it pour.

That’s what The Babadook is really about, and why I found it not so much terrifying as honest and recognizable and even, at times, darkly beautiful. We see Grief as the demonic, nightmare presence that it is. We see that it can’t be completely evicted or exorcised or gotten over, but that it must somehow be confronted and … tamed.

“The film has a solid grasp on the mutable, but ever-present pain of loss. The Babadook is particularly special for allowing its monster to live, even if it’s locked in the basement, acknowledging that Sam and Amelia’s shared darkness isn’t a parasite to be eradicated,“ one reviewer wrote in The Atlantic.

Grief will always be with this mother and child. But the mother learns to soothe its horrible screams. In a scene of heroic maternal bravery, she even brings it something to eat. “Shhhhh,” she says, gently, when it roars at her. She is terrified but she doesn’t turn back. “Shhhhhhh,” she says. “It’s okay.”

When she rejoins her son in the backyard he asks, “How was it?”

“It was quiet today,” she answers.

That is the end. And it is no end at all, but it’s what they can manage.

I sit in the chair in the office of a healer, wanting only the touch of a mother on my back, willing to take any amount of crazy talk and worship music and intercessory prayer to get it.

It was quiet today.