The first Sunday of Advent begins the Catholic Church’s New Year, and in his homily, our priest took the chance to reminded us that here, in the Church, time works differently.

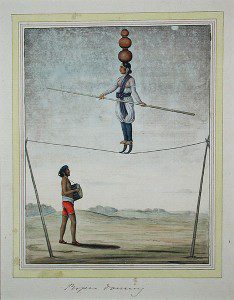

Secular time is a straight line, stretching out ahead indefinitely. I picture the diagram of “the flea and the acrobat” that the science teacher in Stranger Things draws on a paper plate to illustrate how one might exist in an alternate dimension. In fact, I draw it on my song sheet, a straight line and a stick figure, an acrobat walking a wire. She is fixed in the present, the past safely behind, and ahead of her, the unknowable future, which she can’t help but inch toward, however scary it might be.

But in church time, God’s time, it’s not that simple. Or maybe it is much simpler. In God’s time, I am not just the acrobat in the teacher’s diagram; I’m the flea–not limited by the boundaries of clock time, but existing, somehow, during the Mass at least, in some other dimension, one where I am not confined to forward motion. I can move side to side. I can travel around the wire and end up where I started, repeating moments indefinitely. Eternity. Here, I exist in a state of possibility: on the line, inside it, underneath it, or, terrifyingly, nowhere at all. Or perhaps God is the flea, moving at will wherever God likes.

Have I mangled quantum mechanics–not to mention the Catechism–yet? Let me try again.

Christ came. In the past, in the flesh, born in a manger, dressed in swaddling clothes. A human baby was born to a human mother, two thousand years or so ago, and that baby was God, who came to life in a poor man’s body and died among thieves. He was achingly, disturbingly human. Real. The priest mentions the gift of the Rosary, the way the Mysteries walk us through Christ’s life on earth, and I imagine each bead, each prayer, as another step backward on the line, the acrobat suspended above the crowd, gingerly lifting a foot and placing it behind her, the audience holding its breath.

Christ is here. Now, in this church, in this very building. The priest extends his arm to reveal the invisible presence. We come here to meet God, to adore God, to receive God, to taste God, to take God into our bodies. The Acrobat flips to the middle of the wire and lands with a flourish. The crowd gasps.

Christ will come again. In the future, at The End. But this End is not my end. It is only the end of clock time, the destruction of the destroyer: chronos, time, which is nothing less than death, which wears all things to dust. Adventus means coming, and what is coming is not just Christ but the last things: death, judgment, hell and heaven. The acrobat dashes for the safety of the platform. The wire snaps, disappears, poof. A cloud of smoke, a shower of sparks. Or nothing. End scene.

This is what we celebrate on the feast of Christmas. We celebrate the apocalypse, the end of the oppressive reign of chronos, the ushering of us all into kairos, that enduring, eternal moment when everything happens. “Advent is the time to focus on Christ out of time,” says the priest, but later I find that I wrote it down in my notes as “the time to focus on Christ out of mind,” conflating the priest’s words with Bob Dylan’s, which makes me think of Michael Delp writing about Bob Dylan singing to the Good Thief in Paradise, and how this is as good an Advent image as any, all good things gathered together in the enduring moment.

Because Advent, which, in secular America, is little more than an over-scheduled season of frantic rushing from one thing to the next, a grueling forward march from Thanksgiving to Christmas Eve, is, in the Church, a study in eternity.

Adventus. What is coming? Christ is coming. Everything is coming.

I receive the Host from the hands of a fellow parishioner, examine it briefly, imagine in that second that it contains every moment of every soul who ever lived, the births and deaths and everything in between of every body beloved or hated or forgotten, from the first tick of the clock to the last. The Good Thief and Bob Dylan, in my palm and on my tongue.

I balance on the wire.