“It’s a cage. It’s a cage. No, it’s a real cage.’”

–Ta-Nehisi Coates

At age two or three, after dark, I stood on my home’s stoop, the limits of where I was allowed outside the house, and because of the steps up to this vantage point, I could see the man sitting in a cage, naked, or almost naked.

The cage, in the back of a police pick-up, had bright lights attached to the truck and pointed towards the cage. The man in the cage held a calm, steady gaze.

I still scan his face for clues. He stared straight ahead, but sometimes he stared at me. I stared back. In the background noise of this memory, missionaries chattered with police men.

My parents must have explained that he had to go in the police’s pick-up, that he was a man caught stealing from the missionaries, taking sweaters and other warm objects.

I know that I couldn’t understand. We had so much warm clothing. Why must he land in a cage, in the back of a truck, obviously cold, for needing a sweater? Why couldn’t we give him the sweaters? We gave away things all the time?

Dropping into the quiet of this memory over a lifetime, this man and I remain in a silent appraisal of one another.

For the longest time, I couldn’t imagine that people placed other people in cages like that one, and then in my twenties, I asked my father. Yes. And then I saw such a pick up truck, on a trip back to South Africa in 2004.

I never conjure the other men who were South Africans, who lived at this mission station, who took the time to talk to me, taught me their words for greetings. Instead, I talk to the man in the cage. He turns his head away, gazes off stage.

I confess again to him that I don’t want to be this kid, in this space, learning South Africa’s overt race rules, don’t want to be a missionary’s kid, living on a missionary station, eating in a dining hall with men who agreed to preach about Jesus if it also meant basic literacy education.

At eight, when we moved to the States, to Minnesota, we lived in a white working class suburb, and I expected we would soon start attending church in a township. We wouldn’t. Raced places remained, but I learned that we no longer marked the obvious apartheid frame.

Fifty years later, listening to Krista Tippett interviewing Ta-Nehisi Coates, I hear him reference cages, and drop fully into this memory. She is asking for advice on how to address the apartheid realities in the States. What can white people do, once they fully know the extent of continuing racism, and Coates says:

Yeah, no, and there’s no immediate action that I can do to get out of this. What the realization is is that me and you are here trapped together — that you’re as trapped as I am; that once you are aware, you’re in the cage too. It’s a different kind of cage; it’s a gilded cage, but it’s a cage.

[laughter]

It’s a cage. It’s a cage. No, it’s a real cage — and that there’s no real thing that will probably save you in this lifetime.

But why should it? How long did it take to build this? You’re just becoming aware of something that — of a process that was going on long before you were born. So I think it’s natural that the first thing you say is, “How can I get out?”

In the mornings before and after this childhood memory, South African men would wave to me on my stoop as they walked from dorms to classes, or to the dining hall. I would wave back. We would call out greetings to one another. I would recognize each man, would link his face with the words he liked to use.

My mother, telling the story of my early childhood would say, you were so friendly with these men, so insistent on greeting each man, so intent on learning the words each one patiently taught you.

I have no memory of these exchanges. Instead, I’m repeatedly drawn to this man, staring at me, silent, to the exact feeling of confusion that I experienced. He felt then, and also now as if he were so aware, so steadily aware.

Note: This is a set of memories, and I don’t know veracity. I do know that this is how I remember this past.

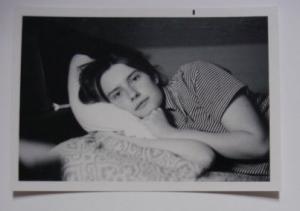

Another note: The attached image is one from my father, one that I’ve altered. I realize I don’t remember this home, but in this image, the front of this home includes stairs up to a porch, a place I called the stoop, spelled, perhaps, stoep, were I wanting to mark Dutch influence on colonial South Africa.

Angela Crow can be found near keyboards, mud, or bicycles. When she’s not creating functional pottery, she writes about embodied literacies, specifically focused on bicycling and walking, and the challenges at stake for us as we explore freedom of movement in a culture that caters to motorized vehicles. She teaches writing, specifically concentrating on contemporary digital literacies for professional and technical writers.

“Approaching Mystery” is a regular feature on Sick Pilgrim curated by Joanna Penn Cooper in which we post vignettes that dwell on the mystery of the everyday, that hang in an unresolved (and unresolvable) space of wonder and unknowability.