When I read the Christmas stories in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, I’m often struck by the paradoxes. That is to say, two things that seem like they shouldn’t be joined come together around the birth of Jesus. Advent and Christmas are seasons full of both/and, of now and not yet. The liturgy of the season challenges us to both remember the events surrounding Christ’s birth in the past and anticipate Christ’s coming again in the future. The past and the future come together in the present. I’m sure there’s a whole list of both/ands we could come up with as we read the Christmas stories. Here’s my top three:

When I read the Christmas stories in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, I’m often struck by the paradoxes. That is to say, two things that seem like they shouldn’t be joined come together around the birth of Jesus. Advent and Christmas are seasons full of both/and, of now and not yet. The liturgy of the season challenges us to both remember the events surrounding Christ’s birth in the past and anticipate Christ’s coming again in the future. The past and the future come together in the present. I’m sure there’s a whole list of both/ands we could come up with as we read the Christmas stories. Here’s my top three:

1. Christmas is a season of both light and dark.

The Scriptures proclaim that God’s Light shines in the darkness of our lives, and that it is a Light that no darkness overcome (John 1:1-5). But that doesn’t negate the reality of darkness in our world. The world Jesus enters isn’t the world depicted on a Hallmark card. He was born during the Pax Romana, when Caesar Augustus was viewed as Lord and Savior of the World by citizens of Rome because of his military conquests. But to average residents of territories Rome occupied, like Mary and Joseph, it must have felt anything but peaceful. Rome’s peace was built on the backs of lower-class people. They were taxed heavily and exploited by the Empire. They knew resistance to Rome was futile; it would be crushed violently. Yes, there was a form of peace, but it was fear that kept the citizens in line.

Likewise, we hear today how “great” our country is—and to be clear it has much that is good and worth celebrating. But there is also a darker side that isn’t as comfortable to talk about. You get branded ungrateful—or even unpatriotic—if you dare to bring it up. As it was during the Pax Romana of Jesus’s day, it seems like the average citizen often doesn’t share in the prosperity and good feelings. (The stock market is booming. Great… I guess. But there’s too much month at the end of my money. How will I make ends meet?)

The fact is, even when on the surface of things, it seems like “all is calm and all is bright,” sometimes our interior world can seem pretty dark. There’s a variety of reasons that cause people to feel that way, but what’s always true is it’s not easy to talk about with others. Sometimes it’s just downright hard to put into words. The malaise is just part of who we are.

There can be feelings of shame associated with feeling blue at a time when we’re supposed to be happy. That’s especially true in a season when we tend to focus so much on upbeat emotions like hope, joy, peace, and love, and get caught up in the made-for-television images of what the season is supposed to look like. The reality is that, in the sanctuary of our soul, the light is flickering and joy can seem like an elusive dream. While it doesn’t stop us from celebrating the season, no matter how many lights we hang up in our house, still the darkness inside us lingers.

When we find ourselves in places where despair threatens to envelop us, when we struggle to find any light, we might remember words from an old Jewish prayer that was found, among other places, inscribed of the walls of one of the hellish places human minds have ever conceived, the concentration camp at Auschwitz

I believe in the Sun, even when it’s not shining.

I believe in Love, even when I don’t feel it.

I believe in God, even when God is silent.

2. Christmas is a season of both goodness and evil.

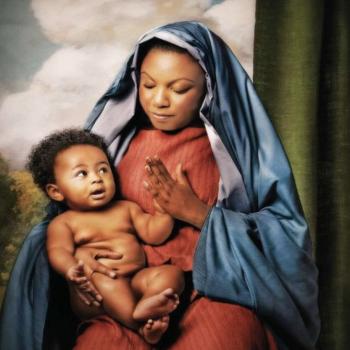

We usually end the Christmas story at the manger—a scene that amalgamates Luke 2:1-20 with Matthew 1:18–2:11. We have the classic image of Joseph and Mary, new parents, young and unmarried, and yet somehow they smile. Shepherds and wise men crowd in to see the newborn baby—and yet he sleeps! Barn animals, normally skittish, are seemingly at ease in the presence of the Holy Family and all those interlopers at the manger, drawn by the proclamations of angels and the star above the stable. While we might debate how “realistic” the picture is, it’s certainly a beautiful image for Christmas—and a great yearly photo-op for parents to get their kids in bathrobes and fabric angel wings., and holding shepherd crooks and fake gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. And it’s not without precedent theologically; it matches Isaiah’s vision of the peaceable kingdom—Isaiah 11. It gives a glimpse how things will be “on that day” when God’s Kingdom comes in its fullness. But we recognize it is not this day. The world is not as it will one day be.

This day often seems more in line with what comes in Luke 2:13-18, what we know as the Massacre of the Infants or the “Holy Innocents.” For obvious reasons, this is not typically included as part of the kids Christmas Eve pageant, and honestly you don’t even hear the passage read all that often (outside of the feast day in the Catholic Church, December 26). (which also tends to be one of the lightest attendance days of the year for most churches.) In the span of a few verses of Scripture, the rating suddenly turns from G to R. The serene peace of the manger is shattered by the realities that a peasant couple like Mary and Joseph could face in that time at the whim of a paranoid despot like Herod. (As if Augustus had not caused enough headaches with his census proclamation.)

Suddenly the Holy Family become refugees forced to flee to another country to escape an impossible situation in their homeland. Does this have any parallels to the today’s world? Did Egypt welcome them with open arms? Scripture is silent on that subject, but history shows we aren’t always the most welcoming toward immigrants, especially when they come from the lower socioeconomic strata. What is clear—when you read the whole story in Luke 1–2—is that Christmas was a time when God’s great goodness met the realities of human evil and sin, when idealized images of peace contrasted sharply with the hardscrabble existence of oppressed minorities on the run.

3. Christmas is a season of both presence and absence.

Maybe the best way to say this in the context of the Christmas story was that acute absence was filled by God’s Presence. The Jewish people had waited for centuries for the Messiah to come. When John the Baptist came on the scene, telling the people to prepare the way for Jesus (Luke 3, after the birth narrative), it had been 400 years since the last Prophet had spoken. In fact, it seems the people waited so long that they may have forgotten exactly for whom they had been waited. When Jesus presented himself as the one that had been promised for centuries, those on the fringes welcomed him happily and recognized him as Savior, but those in power (both religious and political) wanted no part of him; in fact, they wanted him dead. But, of course, that’s the story of another liturgical season.

I had a moment at the Blue Christmas service we held at our church this year when this paradox of Christmas reality hit me personally. We were reading a liturgy where we recognized the reality that while this is the season that we celebrate God’s Presence coming to be with us, for a variety of reasons, some feel absence or loss. We came to the moment when the liturgy said:

We pause now for you to tell the God who longs to take you by the hand and says to you, do not fear, I will help you, about some areas where you need help in finding courage. (Pause)

Right around the time we were reading about the God who longs to take us by the hand, I felt a presence. It was my daughter Rebecca—age 10. She had come into the sanctuary and scrambled over top of me to sit on the pew next to me and put her arm around me like she will still do at times. (I’m sure I’ll miss it when she stops.)

It struck me that as I felt her presence on one side of me I could feel absence on the other—not the first time I’ve experienced the sensation with Becca. And in that moment, I remembered that as I prepare to celebrate another Christmas with my daughter, there is a daughter who is acutely absent—Becca’s twin Hope (aptly named, don’t you think?) who lived only two days before she passed from life support to life eternal. I never got to spend a Christmas with Hope and although I can go for stretches without thinking of her, there are moments that grab me and remind me of the absence of her presence in my life.

Finding Peace in the Midst of Paradox

Being the father of identical twins, only one of whom is now a healthy ten-year-old, means that I live a sort of daily paradox. The name Rebecca means “to bind”, and it seems fitting because there is a sense that Rebecca forever binds me to Hope. If ever I don’t think of Hope for a day, seeing Rebecca—her identical twin—brings me straight back to Hope. Through her, I get a daily reminder what Hope would have looked like (though her personality surely would have been different, and I would give anything to know that part of her). But it’s also bittersweet, because, as it did during the Blue Christmas Service, Becca’s intimate presence can also remind me of the acute absence of Hope.

The good news is, although I never can spend Christmas with Hope, because Christ lives in me (Galatians 2:19-20), I always have HOPE at Christmas.

In Christ, God came to be with us in all of life’s paradoxes: birth and death, joy and sorrow, celebrations and suffering, times of thriving and times of barely surviving. I know all too well that all of these can exist side-by-side.

Alan Ward is a NASA Science Writer married to a United Methodist pastor. His marriage is living proof

science and faith can and do exist in harmony. He and his wife Laurie live in Waldorf. Maryland, where they

are raising their two children this side of eternity: Brady (almost 13) and Becca (10). Alan loves telling

stories of all sorts and believes that One Story weaves together all the other stories we tell. His blog,

“Threads of Glory,” explores these connections—http://bigalscorner.blogspot.com.