Lent is a season, yes, a time. But it is also a place. Lent is Wilderness, a ruin, a wasteland.

During these weeks, we learn of Jesus in the Wilderness. For 40 days, he’s stuck with himself and his thoughts and prayers amid the barren land and empty sky. When The Adversary arrives, at least Jesus has someone to talk to–even as he is tempted to eat, to commit suicide, to bow down and worship. It’s all very unsettling. Lent is supposed to be unsettling. For the rest of the Christian year, we are far too settled with God, the Church, and ourselves. Let us be unsettled.

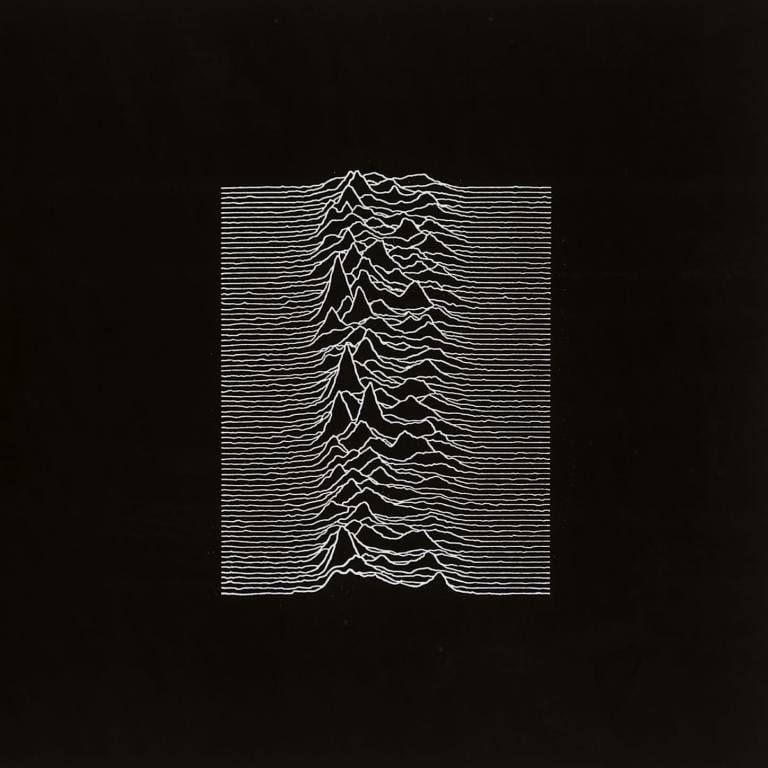

The post-punk band Joy Division growled a brief and gasping life during the latter half of the 1970s in Manchester, England. Lead singer Ian Curtis crafted mournful, panicking lyrics inspired by his personal agonies and the literature he read. Joy Division is the literary kind of band that does not seek to explain itself. It doesn’t have the time. Instead, it’s trying to exorcise its own demons as fast as it can, seeking a relief that shall not come. I resisted listening to Joy Division for many years, residing in the dance-club safety of its second incarnation, New Order. But I couldn’t escape the resonance. It kept calling me. There is something irresistible about ruins.

It’s not my intention to Christianize Joy Division, but I find it impossible to ignore lyrics so informed by a particular experience of Christianity. I can only glean from source material (and don’t we also claim such things about Scripture?). “Wilderness,” from the debut album Unknown Pleasures, casts a pale light upon uncomfortable truths. This is Curtis’s deep and idiosyncratic reading of The Book of Revelation, a vision of apocalypse and tears.

Striding in on a sweeping, macabre baseline, Curtis transforms himself into a dark John of Patmos. His is not a vision about the triumph of good over evil, the establishment of the New Jerusalem, and the ultimate reconciliation between God and humanity. No, this is real apocalypse, both revealing and desolating. The Wilderness is the stark landscape Christendom has established and rules. This song is about the atrocities committed by an oppressive Church.

The Wilderness is the stark landscape Christendom has established and rules.

Curtis reveals himself to be a traveler of distance and time, one who has seen the course of history. We beg this traveler for information and the song becomes antiphonal:

“What did you see there?!”

“I saw the saints and their toys.”

Feeding our hunger, he points out those luminaries of the Church, but they are like children. They are useless. What good are our saints when it comes down to it? Are not our candles and icons mere objects to clench in reassurance?

“What did you see there?!”

“I saw all knowledge destroyed.”

He has seen the dogmatic force of the institutional Church to suppress truth. We still don’t know the whole truth of the ecclesial atrocity: Pedophile Catholic priests. Southern Baptist sexual abuse. Centuries of theologically-justified slavery, oppression, and exploitation. Anti-LGBTQI conversion therapy, shame, and exile. Rampant machismo and sexism. Fundamentalist creationism and anti-intellectualism. We will never know everything.

“I traveled far and wide through many different times,” Curtis goes on, and with growling guitars and staccato snares, we follow him through the Wilderness, through the places where the Church has wreaked havoc.

“I traveled far and wide through the prisons of the Cross.” It never ends.

“What did you see there?!”

“The power and glory of sin.”

The hegemonic Church has sinned. Verily, verily I say to you, we cannot never begin to have a proper ecclesiology without an honest and penitent account and confession of–and atonement for–the horrors of the Christian Church. It must never be buried, forgotten, or ignored. If Ash Wednesday tells us anything, it tells us we are mortal and finite and fallible. We are going to die and in the course of this one life we have, if we are to take Christianity and our mortality seriously, we must recognize the injustice that is a part of mortality and humanness. Only then can forgiveness begin.

“What did you see there?!”

“The blood of Christ on their skins.”

The second half of Revelation 1:5 describes this macabre scene: “Unto him that loved us, and washed us from our sins in his own blood.” Curtis proclaims this bloodbath for what it is. He sees people marked with the salvific gore of the crucified god.

“I traveled far and wide through many different times.” The travel is relentless, repetitive. There is no end to the Wilderness. He keeps reminding us of this. He cannot rest. We cannot rest. Any information is better than no information. The devil you know is better than the alternative.

“I traveled far and wide and unknown martyrs died.” Here is the brutal paradox of the unknown martyrs: they died for their faith and by their nature stand as examples to be known, but what good for others is their act of defiance and faithfulness? Everything is meaningless.

“What did you see there?!”

“I saw the one-sided trials.”

Justice is absent as the powerful pass judgment in their own favor. Curtis’s words are akin to those of so many prophets, so many visionaries of the Bible. But there is nothing, no one to save the oppressed. The Church that preaches salvation is the very mechanism of cruelty and judgment. There can only be one thing left: mourning.

“What did you see there?!”

“I saw the tears as they cried.

They had tears in their eyes.

Tears in their eyes!

Tears in their eyes!

Tears in their eyes!”

Only lamentation can remain. He cannot affect change. He can only make us aware of the perpetual and wide-ranging horror and trauma wrought upon our fellow human beings. He is a visionary, this Ian of Manchester. Joy Division merely sets this revelation, this revealing, this apocalypse to something not quite danceable, but thoroughly entrancing.

“Wilderness” turns the traditional Christian imagery about wasteland and exile on its head. Instead of the Israelites wandering for forty years until reaching the promised land or Jesus being tempted by the devil for 40 days, Curtis sees only an endless wasteland, and it is the Church. Where is God? Did it take so long for me to ask this question? Is there something apophatic or absurd happening? Has God absconded or worse?

What is present in the Wilderness is us. We are here. Alone and together, we are here. And this is a purpose of Lent.

The acknowledgment of Lent requires one’s circumspection about finitude and failure. Yet as we prioritize our individual and personal failings and sin, we risk neglect and omission of the failings and sins committed by the very institutions and theologies of the Church. If we are the be truly circumspect in this our Lent, we must admit not only our own individual limits and failures, but the failures of that institution within which we are a part. In “Wilderness”, obliquely and otherwise, Joy Division indicts the Church for what it has seized and who it has abandoned.

It is Friday, the first Friday of Lent. We have washed off our ashes, but for the time being, we remain in our wilderness. Let us reflect upon our mortality, but let us not forget that we do this alone together. Lent is treated as a short time of self-denial, a time to “give up” the things and habits that impede our relationship with God. But Lent is so much worse, and so much more necessary. It is a time and a place of exploration. What we discover here, however, may horrify us and bring us, ourselves, to tears.

This essay was contributed by Burke Gerstenschlager, a writer and former academic book editor living in Brooklyn, New York. We discoverd Burke through his blog, Bleak Theology.