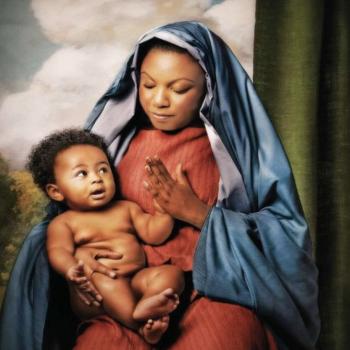

A deep spiritual friend and mentor is the founder of an Orthodox monastery on the Isle of Mull, which among other things seeks to recover Egyptian iconographic style within a Celtic context. When he sent me the image of a Theotokos icon that he had commissioned, I could not look away from her eyes. Thus began a relationship with the icon that has led to its original now having pride of place in my home.

I am a Protestant captivated by Mary, Theotokos. Is this an odd thing? Does it require explanation?

The history of the shifting fate of Mary within Protestantism is a long, complex story that would have to include so many fraught moments:

- How Martin Luther saw Mary in her humanity – her obedience to God’s call as an unwed, scared teenage woman chosen by God precisely as another instance of God bringing salvation out of that which is unimpressive – as a crucial protagonist of the story of humanity’s redemption. He regularly defended her title Theotokos against Nestorian tendencies and he personally believed in her perpetual virginity, although belief in the latter is not mandated by the Lutheran Confessions.

- How subsequent Lutheranism and other Protestant movements, in a frenzy to distinguish their piety from Roman Catholicism, gradually identified Marian devotion with idolatry and went overboard in denigrating her standing (see Beth Kreitzer’s sobering study, Reforming Mary (Oxford University Press, 2004)). This split was of course exacerbated by the fact that Marian devotion became tied up with controversies over papal infallibility, with both undisputed ex cathedra pronouncements by Popes in history related to Marian dogma.

- How the fall of Mary within Protestantism coincided with the rise of the domestic ideal of family within European and North American Protestantism especially – instead of Marian feasts, we have Mother’s Day as the new liturgical ground zero of pious vocation.

- The sense that many Protestants who ordain women to the ministry have that Marian devotion often functions as a way of “promoting women sideways” – honoring a specific woman in her vocation so as to undercut the possibility that women might move into other vocations, such as the priesthood.

Both post-Vatican II ecumenism and plain old postmodernity have colluded, though, to make the lines around Marian appreciation that have hardened over the last 500 years more porous. Christians among different streams of the tradition are better able to receive each other’s gifts; and perhaps even more importantly, in an increasingly secular age defined by multiple and shifting identities and loyalties even among those who consider themselves “the faithful,” raw human connection sometimes supersedes rote confessionalism to allow for new modes of devotion.

That has been the case for me. When Marian devotion is presented to me laden with what I take to be distracting superadditions to her humanity – and here I have to include the formalization of the Immaculate Conception as well as insistence upon perpetual virginity – then she seems quite far away from even the most tradition-friendly Protestant piety. But when it is precisely as a broken, fragile human who took the incredible risk of saying “yes” to a God whom she surely could not have understood at that moment, or in so many moments along the way: it is then that I can cast eyes on her – and feel her eyes on me – as the Mother of the faith that so often seems crazy and dangerous to me as well.

As a professor at a relatively progressive seminary, I have been formed in enough feminist theology to where I do not suffer from an overly masculinized God image; thus, I do not need Mary to somehow feminize the face of God. But Protestants have a different problem. We have – along with much of Western Christianity in general – often succumbed to understandings of sin and atonement that turn God into the problem to be solved – God’s wrath, God’s justice, rather than the forces of sin and death that hold humanity captive, become the problems to which atonement is addressed. Marian devotion can, of course, exacerbate this theological trend if her mediation between God and the believer is understood to be that of a “soft” advocate who can somehow wrangle mercy out of an otherwise implacable Triune judge. But the figure of Mary also stands at the center of an arguably more ancient understanding of atonement – one in which Christ recapitulates the broken actions of the collective “adam” (humanity) in such a way that Christ fulfills the potential of humanity as God intended us to be. This is, after all, the real point of the doctrine of Christ’s sinlessness – that sin is not constitutive of humanity but in fact diminishes it, such that Christ in fulfilling God’s purposes for humanity is in fact more human than we are.

Mary is not Christ. But her recapitulating actions, her courageous faithfulness, over and against the brokenness of human disobedience to the call of life in God (often captured iconographically in Eve/Mary comparisons, although these should be deployed with an awareness of some difficult gender moments in the tradition) allows her to shine as our advocate precisely as one who makes the brave choice for God’s “yes” in the midst of deep danger and uncertainty. She fulfills life precisely as one who knows its brokenness like a sword that pierces hearts.

Mary’s Magnificat is the hymn of praise to precisely this reality: God’s faithfulness as a restoration of human possibility over and against the principalities and powers that bind us. She is the obedient one who shows a more abundant life in obedience than can be found in the fetters of unlimited license within the arenas of exploitation and death with which she and all her people would have been intimately familiar in occupied Roman territory. She says yes to bearing the life that she will see those forces kill on the cross. Her song announces resurrection as insurrection.

It is from within the depth of brokenness and death – the real problems to be solved – that she chooses God’s future. She is the risky “yes” that God intends for our lives to be. And I believe she remains so, with her eyes upon us as the call of that risk continues.

*****

Robert Saler is a new regular contributor to Sick Pilgrim. He is associate dean and research professor of Lutheran studies at Christian Theological Seminary in Indianapolis, IN.