Cinema Divina: Spiritual Development through Contemporary Film

One of the most spiritually powerful essays I have ever read is “To Fall in Love with the World: Individualism and Self-Transcendence in American Life” by John M. Staudenmeier, S.J. (Institute of Jesuit Studies, May 1994). The author asks: “How can we respond to the call of faith and live committed to something other than our individual selves without an impossibly violent rejection of our culture?” In his cultural analysis Staudenmeier addresses the ambiguity of being in the world and not of it, and the need for an inner discipline that “honors our urgent hunger for self-understanding and respects the anxieties that burden us while instilling the confidence and courage it takes to love the world.”

Fourteen years later, his thesis still seems spot-on for us 21st-century capitalists and consumers. Staudenmeier concludes that we can be active participants in the world today without becoming isolated, self-absorbed outsiders. I think his faithfully critical and incarnational approach to the world reminds us not to hide our light under a bushel but to shine it for the global village in which we live.

Lectio Divina

How can we live out Staudenmeier’s thesis? He uses the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius to respond to his theme. My thoughts, however, move to the phenomenon of a renewed interest in the ancient spiritual practice of lectio divina. This spiritual practice is a firm portal by which we can engage our noisy, over-stimulating, and technologically mediated world. Lectio divina, and by extension, cinema divina, can lead us to spiritual growth and sharing our light with the world.

The basic principle of lectio divina is that it is an authentic encounter with God through the Scriptures. Lectio divina means spiritual reading, but is more than meditation.

Many people of all traditions throughout the Christian community practice lectio daily; religious who live in community may practice lectio as shared prayer on a regular basis. When communities share lectio, the Holy Spirit opens minds and hearts allowing genuine spiritual growth to happen.

Practitioners general recognize the following steps of lectio divina:

• Lectio means reading. It involves a basic literary analysis; that is, one looks at the context, words and images, characters, form, genre, and structure of the Scriptures for the day or the coming Sunday.

• Meditatio takes account of both the content of the passage and the present dispositions of the reader; instead of the reader choosing the verse he or she likes best, the reader is grasped by the themes that emerge.

• Oratio, spontaneous prayer, flows from reading and meditating on the text.

• Contemplatio means relishing the spiritual experience and praising God for it.

• Actio is discerning a course of action beyond oneself into the world. The central aspect of lectio divina is that it puts us in a different relationship to the Scriptures.

We are used to choosing the verses that we like; in lectio divina, the Scripture chooses us.

Cinema Divina

Whereas lectio divina is rooted in medieval monasticism and continues to be one of the most valid and universal of spiritual exercises, the concept of cinema divina emerged from contemporary monasticism. In 1977 Matthias Neuman, OSB, expanded the meaning of lectio from the printed text of God’s word in the Scriptures to finding God in modern media stories. He wrote, “Beyond the written word, the giant visual image of the modern movie screen may provide the impetus for an authentic lectio.” (“The Contemporary Spirituality of the Monastic Lectio,” Review for Religious, Volume 36, 1977). Benedict Auer, OSB, takes this a step further in his 1991 article, “Video Divina: A Benedictine Approach to Spiritual Viewing” (Review for Religious, Mar/April 1991): “Video [cinema] divina requires a set disposition which says ‘This evening, I wish to get closer to God so I think I’m going to watch this film which might give me better insights into myself or why my neighbor acts as she or he does….’”

A Theoretical Matrix for Cinema Divina

The National Directory for Catechesis (USCCB, 2005) addresses the influence and role of media and popular culture comprehensively for us: Especially in the U.S., ‘the very evangelization of modern culture depends to a great extent on the influence of the media.’ In fact, the mass media are so influential that they have a culture all their own, which has its own language, customs, and values. Heralds of the Gospel must enter the world of the mass media, learn as much as possible about that culture, evangelize that culture, and determine how best to employ the media to serve the Christian message…

Thus, we are called to engage critically with the media using our faith lenses and discern the media—the movies—we consume. This means that once we choose to see a film we seek to make meaning in that “space” created by the filmmaker between his or her intentions and the education, faith formation, life experience, and expectations that we bring to the cinema story. To engage is the operative word here because this is how we will grow and develop spiritually. To engage with movies does not mean to accommodate them. It means to make informed choices; to watch what we choose mindfully; and to reflect and enter into dialogue, prayer, and action about the cinematic experience.

Cinema divina, then, requires a positive yet critical attitude toward media—in this case movies—a willingness to emerge from our cultural comfort zone to love the world today, and the disposition to embrace cinema as a spiritual experience according to the model of lectio divina. Creation is the first medium of God’s self-communication to us. The person of Jesus Christ, God’s inspired Word in the Scriptures, and the teachings of the Church continue this communication. Through stories old and new, and through cinema in a particular way, God speaks to us. As famed Jesuit Anthony De Mello used to say, “The shortest distance between the truth and the human person is a story.”

Some films that are ideally suited to cinema divina, though they may deal with difficult themes, are Into the Wild; The Shawshank Redemption; Babette’s Feast; Millions; Chocolat; Big Fish; About Schmidt; Life as a House; Bowling for Columbine; Pay It Forward; Field of Dreams; Cry, the Beloved Country; Remember the Titans; Finding Forrester; Steel Magnolias; Enchanted April; Volver. Mostly Martha, The Impossible, Les Miserables (2012), Life of Pi, Where Do We Go Now? The Odd Life of Timothy Green, The Station Agent, Chasing Mavericks, Rise of the Guardians, The Help, The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel, The Tree of Life, How to Train Your Dragon, Henry Poole was Here, Avatar, Julie & Julia, Big Night, Crazy Heart, The Soloist, Knowing, Where the Wild Things Are, Beasts of the Southern Wild, The Blind Side, Up, Nine

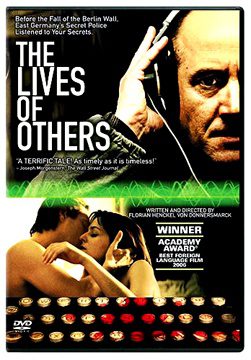

Cinema Divina: The Lives of Others

The German movie The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen) won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 2007. Now available on DVD with English subtitles, The Lives of Others is the best film I have seen in ten years. Like the Biblical books of Esther and The Song of Songs, the name of God is not in the film, yet the reality of God is present in the artistry of the film itself and the narrative about the selfless actions of people who are willing to risk their lives for others.

A Cinema Divina Guide

The Lives of Others is an ideal film for cinema divina for adults and older teens. As with lectio divina, the steps of cinema divina can flow from one to the other and back again; Scripture texts may come spontaneously to mind. If you can, see the film before finishing this article. If this is not possible, I hope the following cinema divina guide will be a practical introduction for individuals and groups into new ways of encountering God through the motion pictures you choose to see.

Lectio: Reading the film

What is the story? What words and images, characters, form, genre, and structure does the filmmaker use to tell the story? If a group is gathered, watch the film and then talk about these elements. A plot summary of The Lives of Others appears below. If you have not seen the film but plan to, you may want to skip reading the summary.

Meditatio: Reflection and resolution

Meditation is a form of mental or unspoken prayer in which a person lets a scene or sequence from the film chose him or her; after quiet reflection, the person resolves to become more God-like. For a group, after some reflection time, each person shares the part of the film that chose him or her and why.

Leaving the preoccupations and anxieties of the day aside, I reflect that The Lives of Others is a history of oppression and inhumanity told through the lives of artists; at the same time it is about the power of art to transcend inhumanity and transform people to move beyond what is safe and sure to risk their lives for others. The part of the film that “chose” me was Weisler’s reaction when Dreyman played “Sonata for a Good Man” and asked Christa-Maria, “Can anyone who has heard this music, I mean really heard it, be a bad person?” I resolve to slow down and listen, really listen, to what God may be saying to me through the people with whom I live and share faith; through music, film, paintings, photography and literature, both fiction and non-fiction, and through the news.

Oratio: spontaneous prayer

The spontaneous prayer flows from reading and meditating on the film. For a group, allow some more quiet time and allow each one to share a prayer from the heart. Here’s my prayer:

Dear God, you see that I am in tears and that I have goose bumps from watching the transformation of this Stasi agent from an unfeeling man following orders to a man who is aware of art and humanity as if encountering his own soul for the first time. When he learns to feel by listening and seeing art and creativity in the lives of others it is like an invitation to me to do the same, and for once, to become meaningful in other’s lives. I feel that all is grace when the characters speak of hope, the soul, faith, love, and even though it was just an archaic cliché for them, a guardian angel, because this is who Weisler became for them. Though they did not mention you, Lord, beauty and art are powerful because their source is in your creation and your self-communicating love. A psalm comes to mind and I bless you Lord for this story and the people who made it: “Praise the Lord, O my soul; all my inmost being, praise his holy name. Praise the Lord, O my soul, and forget not all his benefits, who forgives all your sins and heals all your diseases, who redeems your life from the pit and crowns you with love and compassion, who satisfies your desires with good things, so that your youth is renewed like the eagle’s.” (Ps 103: 1-5).

Contemplatio: Unspoken prayer To contemplate is an unspoken form of prayer in which a person rests with God and converses with God as the Spirit moves within. For a group, allow more quiet time to savor the moments. This is my favorite part of the practice of cinema divina. To contemplate means to rest with the film; to relish it; to savor the memory of the film as a spiritual experience, especially the part that “chose” me as it played back in my imagination, and to praise God for it.

Actio: Action

To discern some course of action beyond oneself into the world is the fruit of the practice of cinema divina as prayer. For a group, after contemplatio the leader invites the group to consider action; after a few moments, invite them to share one way they will carry the fruit of cinema divina into the world.

By moving beyond individual, personal prayer through action, we can grow spiritually and meaningfully and love the world as it is, even as we seek to transform it in and through Christ. As state and federal budgets for the arts for elementary, middle, junior, and high schools continue to be cut, I will write a letter, make a phone call or donation to lobby and support for the arts in education because the arts promote peace; I will acknowledge the validity of the arts by thinking of creative ways to integrate film clips or music into the curriculum and my teaching; I will research more on what the Church teaches about art, artists, communication, and media; I will talk about this film experience with my family and colleagues.

Conclusion

We have been holding Cinema Divina nights for folks 18 and up once a month at our Pauline Center for Media Studies for almost ten years, though we used to call them “Movie Bible Nights”. If this is something you would like to do, check out the four books by Peter Malone and I, the Lights, Camera, Faith series, that places major motion pictures in dialogue with scripture. For the last two years we have had “Meeting Jesus at the Movies” on Saturday afternoon for kids 10-14 and their parents. To screen movies legally be sure to obtain the proper license from Christian Video Licensing International: www.cvli.com.

Rose Pacatte, FSP, is a Daughter of St. Paul and the Director of the Pauline Center for Media Studies in Culver City, CA.

Plot Summary: The Lives of Others It is 1984 and Hauptmann Gerd Wiesler, codename HGW XX/7, a 20-year veteran of the East German secret police, trains recruits at the Stasi academy in East Berlin. He plays a recording to demonstrate interrogation methods. Anton Grubitz, Weisler’s old friend and superior, invites him to the theater and talks about how subversive writers and artists can be. While Wiesler observes the playwright, Georg Dreyman, and comments that he may require surveillance, Grubitz speaks with the Culture Department Minister Hempf. Hempf tells Grubitz to bug Dreyman’s apartment, ostensibly to see if he is loyal to the party, but really to arrest him so that he can then have Dreyman’s girlfriend, Christa-Maria Seiland, who is the star of the play. Grubitz assigns the case to Wiesler, telling him that if he is successful, there is a promotion in it for both of them.

For Dreyman’s birthday he receives a novel by Brecht and sheet music for the piano from his blacklisted friend and mentor, Albert Jerska. The piece is entitled “Sonata for a Good Man.” Jerska is depressed and soon kills himself. Weisler, who has been listening to everything going on in the apartment (and even broke in and stole the novel by Brecht to read) calls Dreyman anonymously and tells him of the death of his friend. Deeply saddened, Dreyman goes to the piano and begins to play “Sonata for a Good Man.” He then looks at Christa- Maria and says, “Can anyone who has heard this music, I mean really heard it, be a bad person?” It is a pivotal moment for Weisler. Dreyman begins to research suicide in East Germany and discovers that the government stopped recording data in 1977 because of the high rate of suicides, especially among artists. He and other friends decide he should write about this and sneak the article out of the country. Instead of typing reports about what he is really hearing, Weisler makes up a play and files it as his report.

When the article is published, Grubitz begins to suspect that things are not as they seem and pressures Weisler. Hempf, who has taken Christa-Maria for himself, tires of her and has her arrested for taking unprescribed medication. Grubitz makes Weisler interrogate her and she breaks by telling them where Dreyman has hidden the typewriter he used to write the article. Before the Stasi can get there, Weisler breaks in and takes it. Christa-Maria despairs and walks in front of a truck. Before she dies, Weisler, shocked at what she has done, tries to tell her that Dreyman will be all right.

Weisler is demoted and censors mail for several years before the Berlin Wall falls. He then becomes a letter carrier. Dreyman puts on a revision of his play “Faces of Love,” but memories of Christa-Maria haunt him. He meets Hempf outside the theater and asks why he, of all artists, was never put under surveillance. Hempf tells him he was continually monitored. Dreyman searches his file in the Stasi archives and discovers volumes of surveillance reports that are complete fictions. Even the final report about the Stasi search for the typewriter is a fiction and, like the others, it is signed by HGW XX/7 with a mark of blood.

(This article is derived from Cinema Divina for Teachers: Spiritual Development through Contemporary Film. It appeared originally in Today’s Catholic Teacher January/February 2008)