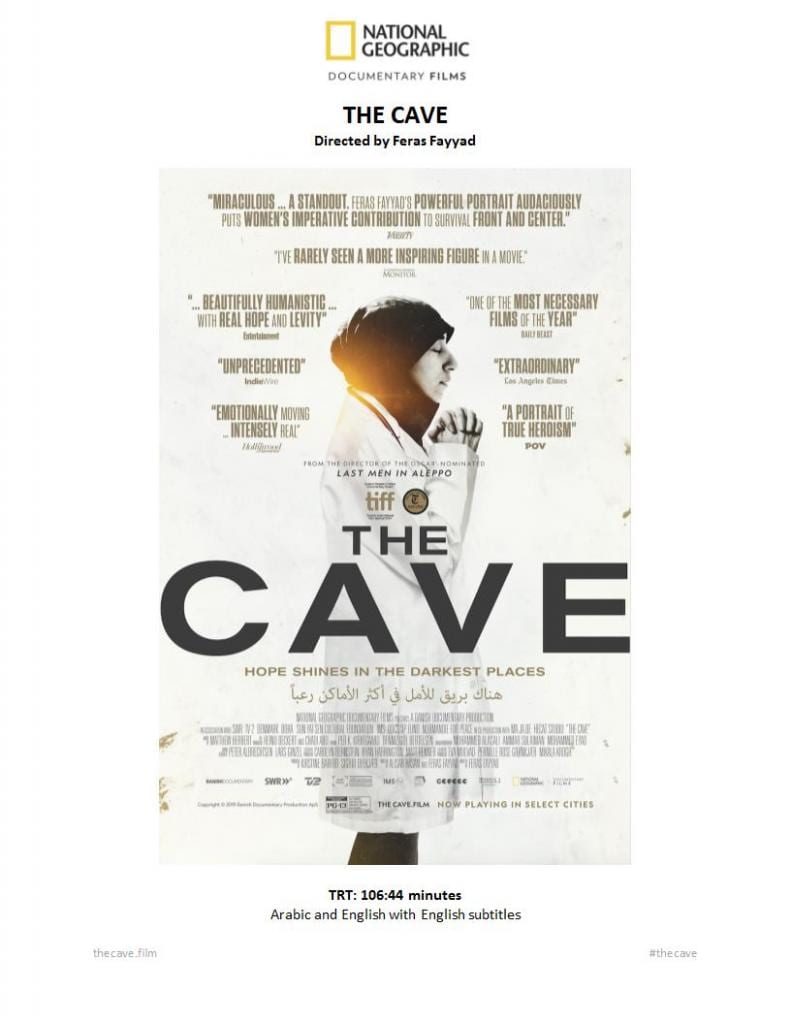

The tragic reality depicted in this year’s Oscar-nominated documentary “The Cave” from director Feras Fayyad (previously nominated for “Last Man in Aleppo”), though filmed in 2018, is real and it is current. Dr. Amani Ballour, a pediatrician and the featured hospital manager in the bombed-out city of Al Ghouta, Syria that is the subject of the film told me in an interview last week: “This movie is the truth, I want the audience to know this. This war on Syria’s people is not something from the past. It is happening right now.”

The tragic reality depicted in this year’s Oscar-nominated documentary “The Cave” from director Feras Fayyad (previously nominated for “Last Man in Aleppo”), though filmed in 2018, is real and it is current. Dr. Amani Ballour, a pediatrician and the featured hospital manager in the bombed-out city of Al Ghouta, Syria that is the subject of the film told me in an interview last week: “This movie is the truth, I want the audience to know this. This war on Syria’s people is not something from the past. It is happening right now.”

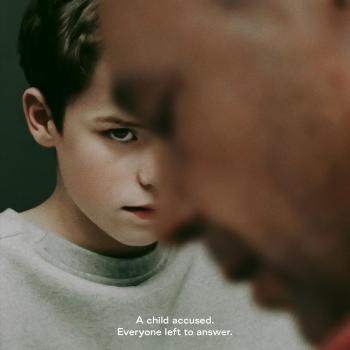

After eight years of war and destruction and the indiscriminate bombing of populated urban areas including hospitals by Syrian forces and its ally, Russia, has killed thousands and displaced millions of people. Dr. Ballour has been appointed manager of the hospital on the eastern side of the city, even though she is a woman. One of the most striking scenes in the film is when a young husband and father begs to have a prescription filled for his sick wife. When Dr. Ballour tells him there is no medicine for her, he turns hostile and insists that if she were a man, there would be medicine. A man would make it happen. He insists she belongs at home (whatever that means in this devastated war-torn country), taking care of her husband and family. Even when the older male surgeon affirms Dr. Ballour’s words, the man cannot and will not accept a female in a managerial role. “It is very frustrating and challening,” Dr. Ballour told me, “to try and change this idea.”

In “The Cave” women doctors and nurses work side by side with their male counterparts to patch together broken bodies of civilians, children and adults, caught in chemical and incendiary attacks ordered by President Assad. Caregivers are forced underground, below the hospital, into a system of caves carved out of what was the hospital basement before the revolution. “We opened up the basement and cleaned it in order to expand some rooms to make it an underground hospital. It took us three or four months to prepare” what looks like a system of tunnels.

The staff tries to maintain normalcy in between air raids and attacks. They prepare a surprise birthday celebration of popcorn and fresh lettuce, obviously a rarity, for Dr. Ballour. The deep green of the lettuce is the one natural bright spot in the film, a true gift in a land without fresh food for its people.

In the end, the end comes and the staff and patients must be evacuated from the hospital. I asked Dr. Ballour, who is 30 years old in the film, and unmarried, how she managed and manages now to keep body and soul together in such dire circumstances when children who had lost both hands in the bombings, were brought to her. “It is not easy to keep yourself together,” she said. “But people need you. I stayed because I wanted to. I was happy when I could help someone. I tried to focus on my work.”

“I was very sad and angry about everything after I left. We tried our best to help, we wanted to stay in our country, our hospital. We were very angry at what had happened, at what is still happening, the displacement of people. I was very hopeless at first but I believe I can help people, women and children today.”

The film is a gritty documentary, yes, but because it is told mostly through the experiences of Dr. Ballour and the female staff, the criminality of attacks on civilians, their cities and their homes, is laid bare for all to see. In fact, the doctors keep track of all the patients and their injuries against the day they can use this information when the perpetrators are brought up on crimes against humanity.

The valiant women and men who work together as a team effort for the sake of their people and under the constant threat of bombing, show a deep love for humanity – the exact opposite of those perpetrating the horror of war and destruction. One of the tag lines for the films says that “From the hell above, there is light below.”

In this National Geographic film, director Fayyad is on the ground in Syria once again, showing the world what is going on, letting us feel through sight and sound, the fear, the lack of security and shelter, what it means to not have enough medicine or anesthesia for surgery. It’s as if the human race has retreated centuries in terms of human, social, and ethical development. The waste of war has never been more clearly stated.

Director Fayyed found the female doctors and nurses working in underground hospitals to be an inspiration and telling their story a way to break the silence about the ongoing brutality so that justice can be achieved and restored (from the press notes.)

I asked Dr. Ballour what she hoped audiences would take away from the film. “I would like them to know that this movie is the truth. I want them to know this situation is not something from the past – it is till happening now. A few days ago, Russian air forces destroyed a hospital [in Ariha, Syria] and in two days 60,000 people displaced. Too many people are suffering in the camps with the cold, and others in prison. When audiences watch this film and know that it is still happening in Syria, I hope they will lend their help, their voices.”