There's an old joke about racist jokes that asks "How does every joke in [insert name of homogenous, xenophobic white neighborhood] begin?" The answer — it's a visual gag — is pantomiming looking over both shoulders suspiciously then leaning forward to whisper.

The point of that joke is that some people talk differently around one set of neighbors than they do around another set of neighbors — and the differences can be revealing.

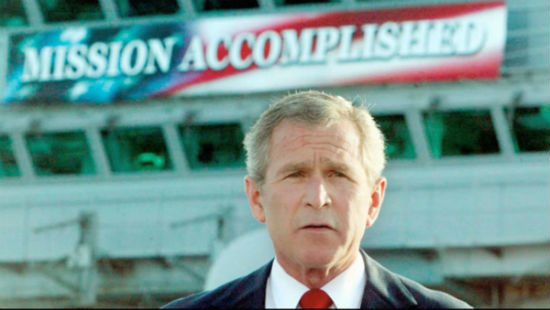

President Bush met with nine writers and editors from prominent conservative religious publications last Wednesday at the White House. Two of the members of the press present — Marvin Olasky of World magazine and Richard John Neuhaus of First Things — were there in the role of "journalists" despite also working as advisers to the president. So the president was on his home turf, speaking to a very supportive audience.

How supportive? The questions the president was asked ranged from the softball — "What do you think about being criticized for open expressions of faith?" "What are you doing to defend traditional marriage?" "Which presidents do you most admire?" — to the oddball — "How can compassionate conservatism be advanced internationally in places like Cuba?"

Some highlights follow, taken from the edited transcript provided by Christianity Today.

On Iraq and/or the GWOT:

We are in the process of transferring full sovereignty and eventual freedom — full sovereignty and freedom — to the Iraqi people as they head towards free elections. …

It's not going to be easy, by the way. People who lived in tyranny, they haven't developed the habits of free people yet. They haven't been free yet. And anyway, I made it clear that the relationship between an occupier and the people of the country will shift to one of free people with the help of a coalition of nations.

In the short run we will use every asset to prevent an enemy from attacking us again. Which I believe they want to do. I believe they want to do it because I know they want to sow discord, distrust, and fear at home so that we begin to withdraw from parts of the world where they would like to have enormous influence to spread their Taliban-like vision — the corruption of religion — to suit their purposes. …

The long-run solution to terror is freedom. That's what we believe in America. We believe that everybody yearns to be free. We believe everybody can be free. Now I'm getting people to research all the statements of doubt about whether or not Japan could be free after World War II. And I suspect we'll find there was quite a bit of cynicism, and people were just flat dubious that people in the Far East — who had a religion that was foreign to most Americans — could conceivably self-govern in a democratic style. Thank goodness the optimists ruled the day …

That last bit about Japan is remarkably revealing. This is the president's response to those who argue that he seems adrift, clueless and planless regarding post-Saddam Iraq. He has the White House dig up examples of cynics from the past — people who criticized a very different nation-building exercise in a very different context — so that he can cast the debate in terms of "optimism" versus pessimism.

Hope is not a plan, but President Bush doesn't even have hope. He has "optimism" — hope's shallow, flaccid, disingenuous cousin.

On Abu Ghraib:

I said I am sorry for those people who were humiliated. That's all I said. I also said, "The great thing about our country is that people will now see that we'll deal with this in a transparent way based upon rule of law. And it will serve as a great contrast." But I never apologized to the Arab world.

President Bush wants to make it very clear: "I never apologized to the Arab world."

Got that?

On Faith-based initiatives:

At home, the job of a president is to help cultures change. The culture needs to be changed. …

Part of government's role is to foster responsibility and hope by standing with those who have heard a call to love a neighbor, which is the second point of the faith-based initiative that I think is one of the most important domestic initiatives that I have pushed, if not the most. It recognizes the rightful relationship between hearts and souls and government. Again, my job is to try to distill things down so that average people can understand it. Here's the way I put it, "Government can hand out money, but it cannot put love in people's hearts or a sense of purpose in people's lives."

Or I like to tell people, "If you're a drunk, sometimes a psychologist can talk you out of it, but generally it requires a higher power. If you change your heart, you change your behavior." And government must recognize that those heart changers are an important part of changing society one soul at a time.

So the faith-based initiative recognizes that there is an army of compassion that needs to be nurtured, rallied, called forth, and funded, without causing the army to have to lose the reason it's an army in the first place.

I mean, one of the real challenges we've had, of course, is to say to the faith community, "Come in, the social service money is available for you and oh, by the way, you can keep the cross on the wall or the Star of David in your temple without fear of government retribution." I think we're getting there. I mean, this is a cultural change in government too, by the way. It's been a mighty struggle to convince people of the wisdom of the policy.

In Texas again, my line was, "Look, don't focus on the process, focus on the results." That's how we were able to get the prison ministry into that Sugarland Prison. "See if these people go back into jail or not, that's all I ask. And if they don't, if it works, let's keep it intact." …

The "focus on the results" approach is the strongest argument for allowing "faith-based" agencies to compete for federal contracts. I'm pretty open to such an argument — but the sincerity of this results-oriented approach is undermined when it's premised on the idea that "culture needs to be changed."

Changed how? Changed from what into what? Bush doesn't say — apparently because, for this particular audience, he doesn't have to say. They know what he means. He means that the faith-based initiative is a way to make America look more like the kind of place that Marvin Olasky and Richard John Neuhaus want it to be. (Note to Bush campaign: "I want to make all of America look just like a Texas prison" may not be a winning argument.)

That argument has nothing to do with the equal consideration of faith-based and secular social service agencies. It has everything to do with using taxpayers' money to advance a particular sectarian notion of morality.

With most journalists, and in front of most audiences, Bush argues for his faith-based initiatives entirely on the basis of the results-oriented argument. The change-the-culture stuff is the sort of thing he only seems to say when he feels safe and certain that most people aren't paying attention.

As for the "army of compassion," allow me to express a Shinsekian skepticism that it has enough troops for the job. Thousands of hard-working, heroic people of faith are doing wonderful things to empower the poor and assist the needy and America is a better place because of their work. But even if you put all these disorganized irregulars together you still wouldn't have an "army of compassion" — only a single, overwhelmed battalion in need of better equipment and training.

This is the simple, empirical fact that stops short all the grand dreams about transforming America through faith-based initiatives. The army of compassion just doesn't have the troops.

On the long-term, growing federal deficit:

Bush didn't say anything about the deficit and the religious writers didn't ask. They were too obsessed with their consuming fear that gay people might enjoy the benefits of married life to consider the ramifications of screwing our children and grandchildren by making them foot the bill for everything from tax cuts to war-profiteering.

Stealing from your grandchildren by leaving them a legacy of odious debt is not, for these religion writers or their president, a "moral" issue.

On the disproportionate effect of tax-cuts for the super-rich and their ultimate effect of eviscerating Social Security and transferring payroll taxes from working families into the wallets of the wealthy:

See above.

On the environment:

Why would religious people care about creation?

On gay marriage:

Government has got a responsibility to support and nurture institutions … foster institutions that provide hope and stability. That's why I took the position I took on the sanctity of marriage. I believe it's a very important issue for America. I think it — marriage — has worked. It's the commitment between a man and a woman. That shared responsibility is the cornerstone — has been the cornerstone — will be the cornerstone for civilization and I think any erosion of that definition by itself will weaken civilization as we have known it, and as we hope to know it.

And I call for a constitutional amendment for two reasons: One, I understand how the process works and why there is some protection against the decisions by a few court judges in one state protecting the definition of marriage in other states. The legal scholars tell me it is not on a very firm foundation because of the Full Faith and Credit Clause of the Constitution. And therefore there needs to be an alternative available. …

Secondly, I want the American people participating in the process. I don't want this decided by judges. It's too big an issue. And the constitutional process is a sure enough way to get people involved through the amendment process, how we amend the Constitution.

I took a strong stand publicly, laid out a constitutional amendment, which in itself becomes a benchmark for people to rally around — in itself was a statement from the presidency that says the country has an alternative to that which they're seeing on their TV screens. And I will continue to explain why I did what I did. … But in order for a constitutional amendment to go forward people have to speak. Now, I'll be glad to lend my voice, but it's going to require more than one voice. It's going to require people from around the country to insist to members of Congress for starters, that a constitutional amendment process is necessary for the country. …

A rough translation here would seem to be: You want an amendment, pass it yourself.

Miscellany:

Text-book example of projection No. 1:

The culture needs to be changed. I call it, so people can understand what I'm talking about, changing the culture from one that says, "If it feels good, do it, and if you've got a problem, blame somebody else," to a culture in which each of us understands we're responsible for the decisions we make in life. I call it the responsibility era.

Text-book example of projection No. 2:

I think what we're dealing with are people — extreme, radical people — who've got a deep desire to spread an ideology that is anti-women, anti-free thought, anti- art and science, you know, that couch their language in religious terms. But that doesn't make them religious people.

Too true:

I'm the kind of person who doesn't change.