If you haven't yet read James Fallows' Atlantic Monthly article, "Bush's Lost Year," then by all means go read it now. (An online version for nonsubscribers was available here, but the link is not working at the time I'm posting this.)

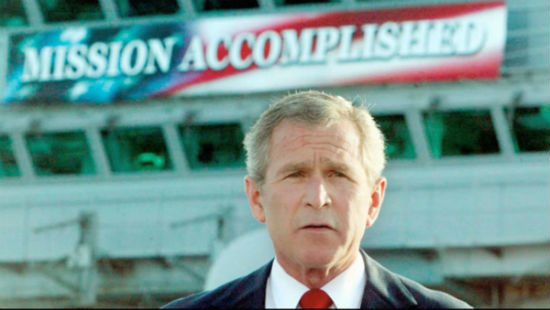

Fallows provides a dismaying summary of the cost and the opportunity costs of President Bush's invasion and occupation of Iraq. Two reactions:

1. James Fallows would make a better president and a better commander in chief than George W. Bush. I say this not because of Fallows' conclusions, but because of the process by which he arrives at those conclusions.

Fallows sought out, spoke with and listened to people with real expertise who know what they are talking about. I do not have the phone numbers of these people in my personal rolodex, but they are not really that difficult to identify and approach. They are busy people with important jobs, but most are willing to carve out some time to meet with a journalist of Fallows' stature. Without a doubt, they also would have been willing to meet with and speak to the president of the United States, had he shown the slightest interest or curiosity in listening to what they had to say. He didn't. That's why he has dragged America into this mess and left our military and our nation without a viable "exit strategy" from quagmire and disaster.

I do not expect our president to be the world's foremost expert on every topic about which the president will have to make important decisions. I do, however, expect our president to consult with and to listen to such experts. Particularly when, as Fallows discovered, they speak with one, united voice.

A buddy of mine in college was taking ROTC classes. When he graduated, he would become a lieutenant in the Army. I asked him one day what he'd learned in class that week. "We learned how to cross a minefield," he told me. I had no idea how one might go about this, so I asked him how you do it.

"You turn to your sergeant," he said, "and you say, 'Sergeant! Get these men across that minefield.'"

It's probably a good thing my friend wasn't training to be a sergeant, or his men might've been in trouble. But there is a kind of wisdom in what he said.

Like me, George W. Bush has no idea how to get across a minefield. But he refuses to ask/order his sergeants to help him.

And any sergeant with the temerity to try to offer counsel is punished for it. The names of Richard Clarke, Joseph Wilson, Gen. Eric Shinseki and Gen. Anthony Zinni arise repeatedly in Fallows article as examples — warnings — of what will happen to anyone who dares to offer President Bush the kind of advice he doesn't want to hear. Fallows does not bring these names up himself — the people he interviews do. The people who might be our best hope for plotting some course to salvage the situation in Iraq and in the global struggle against terrorism have been shunted to the sidelines. They use "Shinseki" as a verb, and they do not wish to get Shinsekied.

2. The most difficult cases for a president arise when the various experts — the people who have most carefully studied, most deeply experienced an issue — do not all agree. In such cases, the president must rely on his own judgment to decide which of his advisers to heed.

The invasion of Iraq was not one of these difficult cases. There is no variation among the experts. Their advice and opinions have a remarkable unanimity.

Here's Fallows:

Over the past two years, I have been talking with a group of people at the working level of America's anti-terrorism efforts. Most are in the military, the intelligence agencies and the diplomatic service; some are in think tanks and nongovernmental agencies. I have come to trust them, because most of them have no partisan ax to grind with the administration (in the nature of things, soldiers and spies are mainly Republicans), and because they have so far been proved right. In the year before combat started in Iraq, they warned that occupying that country would be far harder than conquering it. As the occupation began, they pointed out the existence of plans and warnings the administration seemed determined to ignore.

As a political matter, whether the United States is now safer or more vulnerable is of course ferociously controversial. … But among national-security professionals there is surprisingly little controversy. Except for those in government and in the opinion industries whose job it is to defend the administration's record, they tend to see America's response to 9/11 as a catastrophe.

I have sat through arguments among soldiers and scholars about whether the invasion of Iraq should be considered the worst strategic error in American history — or only the worst since Vietnam. … But about the conduct and effect of the war in Iraq one view prevails: it has increased the threats America faces, and has reduced the military, financial and diplomatic tools with which we can respond.

Fallows discusses President Bush's statement — which summarizes and shapes his overall approach in the war on terror — that, "They hate us for who we are. … They hate us because we are free."

There may be people who have studied, fought against or tried to infiltrate al-Qaida and who agree with Bush's statement. But I have never met any. The soldiers, spies, academics and diplomats I have interviewed are unanimous in saying that "They hate us for who we are" is dangerous claptrap. Dangerous because it is so lazily self-justifying and self-deluding: the only thing we could possibly be doing wrong is being so excellent. Claptrap because it reflects so little knowledge of how Islamic extremism has evolved. …

So the "soldiers, spies, academics and diplomats" are unanimous. But what about the pollsters?

The occupation of Iraq and "They hate us for who we are" is dangerous claptrap to the people whose primary concern is combating terrorism. But to those experts who have a different set of priorities — namely, winning elections at all costs — this claptrap is the key to four more years.