The scientist J.B.S. Haldane, when asked what his studies had taught him about God, famously replied, "I'm not sure, but he seems to be inordinately fond of beetles."

This is excellent theology. There are, after all, more than 350,000 distinct species of beetle, ad majorem Dei gloriam.

This is not to say that such a plethora of species suggests an "entomological argument" for the existence of God. The earth is a beetle-ful place. That much is certain. For those of us who believe in God, this fact, as Haldane observed, suggests something about God's character. But it indicates little for those trying either to prove or to disprove the existence of God.

Jacob Weisberg disagrees. He seems to think, somehow, that this abundance of Coleoptera is incompatible with belief in God. He asserts as much in a Slate article titled "Evolution vs. Religion: Quit pretending they're compatible." I would summarize Weisberg's argument, but he doesn't actually make one. He feels his point is self-evident.

"That evolution erodes religious belief seems almost too obvious to require argument," Weisberg writes. And, "You can believe in both — but not many people do."

And really, that's Weisberg's whole argument. Since "not many people" believe in both God and evolution, these beliefs must be incompatible. If "not many people" believe in something, then they must be wrong and we can pretend that they and their views are of no consequence. Weisberg is so confident in this assertion that he even links to Kenneth R. Miller's fine essay, "Finding Darwin's God," as a curiosity — a perspective to be chortled at, but not engaged.

Miller is, like me, one of those "not many people" who believes in both God and evolution. He's quite accustomed to dealing with Weisberg's assertion that these things are incompatible but, also like me, he's more accustomed to fielding such blanket assertions from the other side — from the "scientific creationists" and their repackaged heirs in the "Intelligent Design" movement.

Miller sees the Intelligent Design argument for what it is: Bad theology.

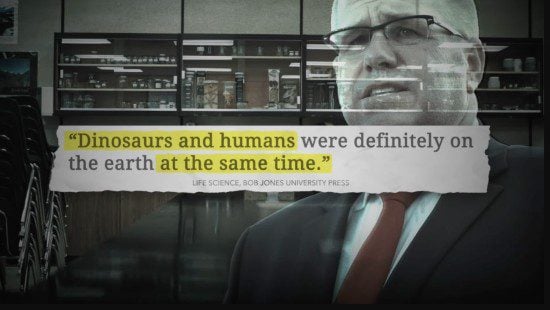

They claim that the existence of life, the appearance of new species, and, most especially, the origins of mankind have not and cannot be explained by evolution or any other natural process. By denying the self-sufficiency of nature, they look for God (or at least a "designer") in the deficiencies of science. The trouble is that science, given enough time, generally explains even the most baffling things. As a matter of strategy, creationists would be well-advised to avoid telling scientists what they will never be able to figure out. History is against them. In a general way, we really do understand how nature works.

And evolution forms a critical part of that understanding. Evolution really does explain the very things that its critics say it does not. Claims disputing the antiquity of the earth, the validity of the fossil record, and the sufficiency of evolutionary mechanisms vanish upon close inspection. Even to the most fervent anti-evolutionists, the pattern should be clear — their favorite "gaps" are filling up: the molecular mechanisms of evolution are now well-understood, and the historical record of evolution becomes more compelling with each passing season. This means that science can answer their challenges to evolution in an obvious way. Show the historical record, provide the data, reveal the mechanism, and highlight the convergence of theory and fact.

There is, however, a deeper problem caused by the opponents of evolution, a problem for religion. … They have based their search for God on the premise that nature is not self-sufficient. By such logic, only God can make a species, just as Father Murphy believed only God could make a flower. Both assertions support the existence of God only so long as these assertions are true, but serious problems for religion emerge when they are shown to be false.

If we accept a lack of scientific explanation as proof for God's existence, simple logic would dictate that we would have to regard a successful scientific explanation as an argument against God. That's why creationist reasoning, ultimately, is much more dangerous to religion than to science. Elliot Meyerowitz's fine work on floral induction suddenly becomes a threat to the divine, even though common sense tells us it should be nothing of the sort.

Bad theology is incompatible with science, but that's not the biggest problem facing it. The more immediate problem facing bad theology is that it is incompatible with good theology.