At Pandagon, Jesse Taylor takes a cynical look the ritualized dismissal-by-praise that has come to accompany this week’s national holiday:

Martin Luther King Day is problematic. It’s problematic because it’s the leading edge of a bifurcation of King’s legacy into what can charitably be called the Disney King and the Real King. The Disney King is the one whose predominant message was a race-ignorant society where recognizing “the content of one’s character” was a command to ignore the entirety of America’s history with race. That King’s message was that a class of people, discriminated against on the basis of race, simply wanted the country to stop thinking about their race. Once that happened, discrimination would end, and the vicious psychological scars of slavery and Jim Crow and racial inequality would be healed. … And scene.

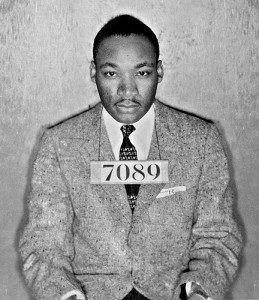

The Real King was a tremendously complex political figure despised by many, who fought for racial justice, and against Vietnam, and who accepted the Margaret Sanger Award from Planned Parenthood. He wasn’t a moderate pragmatist who just really wanted to be able to sit in the front of the bus – the man was, both by the standards of his day and of the present day, a leftist.

That notion of the safe, Disneyfied King is my main reason for answering “probably not” in response to Carl Gregg’s question: “Should MLK’s ‘Letter From a Birmingham Jail’ Be Added to the New Testament?”

I think “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is far too important and inspired to subject it to all the indignities and abuses routinely inflicted on the 27 books of the New Testament canon in the name of reverence. I have too high a view of King’s epistle to the Alabamians to see it subjected to kind of treatment that “a high view of scripture” seems to entail.

I think “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” is far too important and inspired to subject it to all the indignities and abuses routinely inflicted on the 27 books of the New Testament canon in the name of reverence. I have too high a view of King’s epistle to the Alabamians to see it subjected to kind of treatment that “a high view of scripture” seems to entail.

Every January brings us a new set of columns purporting to tell us “What King would say about ________ if he were still alive today.” I’m leery of such arguments unless they’re grounded in what King already said about ________ when he still was alive. The Rev. Irene Monroe offers that grounding in “MLK Day Reflection for LGBTQ Justice in the Black Church.” Monroe’s argument is congruent with the trajectory and the long, bending arc of King’s thought.

Her argument echoes that made by Rep. John Lewis — someone who knew King better than most and who has earned the right to speak on his behalf. Lewis said:

Dr. King used to say when people talked about blacks and whites falling in love and getting married — you know one time in the state of Virginia, in my native state of Alabama, in Georgia and other parts of the South, blacks and whites could not fall in love and get married. And Dr. King took a simple argument and said races don’t fall in love and get married. Individuals fall in love and get married. It’s not the business of the federal government, it’s not the business of the state government to tell two individuals that they cannot fall in love and get married. And so I go back to what I said and wrote those lines a few years ago, that I fought too long and too hard against discrimination based on race and color not to stand up and fight and speak out against discrimination based on sexual orientation.

And you hear people “defending marriage.” Gay marriage is not a threat to heterosexual marriage. It is time for us to put that argument behind us.

You cannot separate the issue of civil rights. It is one of those absolute, immutable principles. You’ve got to have not just civil rights for some, but civil rights for all of us.

Some other highlights from the blogosphere celebrating King below the jump:

Charlie Pierce reminds us of what a president can do when citizens like those rallied by Martin Luther King Jr. force that president to do so, and thereby allow that president to do so.

“On Our National Holiday, America’s Everlasting War“:

Lyndon Johnson, of all people, called the last bluff. In March of 1965, he appeared before Congress to urge the passage of the Voting Rights Act, and he delivered the greatest speech an American president has delivered in my lifetime. He was an operator, far more than half-corrupt, and a Texan besides, but the one thing he wasn’t was mystified. He knew power and he knew that power had no inherent mystery to it. It was raw. It was elemental. And it was power in this country that was changing. He looked the angry South and the comfortable North right in the eye and said it plain:

But rarely in any time does an issue lay bare the secret heart of America itself. Rarely are we met with a challenge, not to our growth or abundance, or our welfare or our security, but rather to the values and the purposes and the meaning of our beloved nation. The issue of equal rights for American Negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, and should we double our wealth and conquer the stars, and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation. For, with a country as with a person, “what is a man profited if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” There is no Negro problem. There is no Southern problem. There is no Northern problem. There is only an American problem.

And then:

But even if we pass this bill the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life. Their cause must be our cause too. Because it’s not just Negroes, but really it’s all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice.

And we shall overcome.

Tom Levenson says “Amen” and quotes more from Johnson’s astonishing, world-changing speech — a speech that, again, Johnson was only able to give because he’d been compelled to do so.

This is from a few years ago, but it’s still timely — Kai Wright: “Dr. King, Forgotten Radical”

We’ve all got reason to avoid the uncomfortable truths King shoved in the nation’s face. It’s a lot easier for African Americans to pine for his leadership than it is to accept our own responsibility for creating the radicalized community he urged upon us. And it’s more comfortable for white America to reduce King’s goals to an idyllic meeting of little black boys and little white girls than it is to consider his analysis of how white supremacy keeps that from becoming reality.

Take, for instance, his point that segregation’s purpose wasn’t just to keep blacks out in the streets but to keep poor whites from taking to them and demanding economic justice. … “The Southern aristocracy took the world and gave the poor white man Jim Crow,” King lectured from the Alabama Capitol steps, following the 1965 march on Selma. “And when his wrinkled stomach cried out for the food that his empty pockets could not provide, he ate Jim Crow, a psychological bird that told him that no matter how bad off he was, at least he was a white man, better than a black man.”

… Black America first anointed King its savior after he stormed onto the national scene in Montgomery, holding together the prolonged 1954 bus boycott with nightly speeches in which he exhorted everyone to stay the course. Jet magazine called him “Alabama’s Modern Moses.” We’ve been waiting for another prophet since he was gunned down on April 4, 1968. I just wish our last one would come back and remind us that our power lies not in leadership but in a collective refusal to be oppressed.

And more:

- R.J. Eskow at Crooks & Liars: “An Illustrated Guide to Dr. King’s 21st Century Insights“

- Brad DeLong: “National Review Celebrates Martin Luther King Day“

- DeLong links to Rick Perlstein: “Conservatives and Martin Luther King“

- Letters of Note: “the FBI anonymously sent Martin Luther King the following threatening letter …“