The Ms. Blog offers a collection of reader-submitted photos of products marketed to people and also to women.

Not to men and to women, but to people — normal, legitimate, regular people, and to women — abnormal, subordinate, irregular not-quite people.

Not to men and to women, but to people — normal, legitimate, regular people, and to women — abnormal, subordinate, irregular not-quite people.

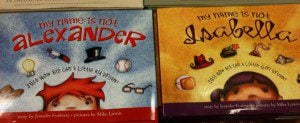

I’ve borrowed one example here, two children’s books presented as unequal companions. One book is for “kids” and the other is for “girls.”

This sends a message, sometimes blatant and sometimes subtle, that half of the world is somehow abnormal.

I’ll confess that I don’t always notice when marketers do this. That’s one of the privileges of privilege. Not only do you get to be told constantly that you’re normal and normative, but you learn to be oblivious to being told this. It’s much harder not to notice when you’re constantly hearing the opposite — that you’re ab-normal or sub-normal and less or other than what normal people ought to be.

Consider, for example, the generic avatar/icon that Disqus provides for commenters who don’t upload their own.

I’d been scrolling past that for months, not noticing anything other than the generic placeholder it was intended to be by the guys who set this up at Disqus.

I didn’t really see what I was looking at — didn’t notice that it’s not so generic at all — until Jam pointed it out to me in an email:

Disqus’ … little default avatar thingy is pretty distinctly male there. [It’s] another little example of “men are human, women are women” kind of thinking … that men are default humans, so especially on the Internet you’re male until proven female.

That phrase “pointed it out” is illustrative of the looking-without-seeing that occurs when our blinders keep us, first of all, from seeing our blinders. That underscores the Doctor’s good advice from the other day (“Because it will change your life“) about the necessity of making it a habit to look again “Exactly where you don’t want to look, where you never want to look.” That’s not a habit most of us can manage on our own, which points again to the necessity of talking to one another and especially to others who bring different perspectives. We all need someone else who can tell us, “Look behind you.”

Jam also linked to Lisa Wade’s collection of default avatars at Sociological Images, which is really interesting and shows that the default-white-dude iconography isn’t just a Disqus phenomenon. For much more on the subject, scroll down to the bottom of Wade’s post for links to other articles on “how certain kinds of people get imagined as just people, while others get imagined as certain kinds of people.” See, for example, Wade’s “The Neutral and the Marked: A Primer for Your Kids.”

That terminology again helps to illustrate the un-seen un-seens of privilege and epistemic closure.* It’s easy not to notice when you’re being told you’re neutral. It’s harder not to notice when you’re being told you’re marked — marked as different, other, abnormal.

The Punning Pundit recently discussed another graphic digital example of this neutral/marked problem in video game design:

One of the great features of Science Fiction (and fantasy) is that it enlarges contemporary mores, memories, and memes to the point where they are more easily viewable. When Bioware, for instance, set out to create non-human species they certainly didn’t think about the fact that they’d be creating a perfect example of women being the “second sex”. The fact that this was done both explicitly – and unintentionally – says volumes about the way contemporary society has failed to understand what feminism means.

The link there goes to this Border House post by rho on “Designing non-human females.” Rho quotes from one video game designer:

They’re all males in the game. We usually try to avoid the females because what do you do with a female Turian? Do you give her breasts? What do you do? Do you put lipstick on her?

And responds:

What I personally take from this is the message that these artists pretty much think of women as being nothing but breasts and lipstick with no other identifying features, that they have very little idea how nature works (hint: birds don’t have breasts), and that they decided that making female characters was hard, so they’d give up.

It’s a fascinating discussion, but I’m not much of a gamer, so let me bring this back closer to home here.

Getting Disqus to evolve may prove hard, but let’s not give up trying. Lisa Wade’s collection of default avatars includes numerous examples that don’t try to be anthropomorphic at all. I’m thinking that’s a smarter, fairer and more inclusive approach than the white-guy silhouette Disqus now uses as its “neutral” icon. Is that the best idea, or should we recommend another approach?

I’m asking because I think the first step is to clarify specifically just what it is we want to ask Disqus to do to fix this. The second step, of course, is to deluge them with firm-but-polite emails urging them to make that fix.

Will that work? I don’t know. But as I read somewhere, “Just how big can a little blog dream?”

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Re-reading that paragraph, it seems too dry and abstract to get at what I’m trying to say there. Think again of that phrase “Look behind you.” Now think of all the times you’ve shouted that at the screen while watching a horror movie. That is what the problem of “privilege and epistemic closure” is like. To be blindered by privilege and thus blindered to privilege is to be in unwitting peril — like Jamie Lee Curtis not knowing that Michael Myers is standing right behind her. It’s not that kind of physical peril, but the moral and cognitive danger is just as real.

Or, in simpler terms, to live blindered by privilege is to be more evil and more stupid than one could otherwise be.

The moral and cognitive damage that privilege can do to the privileged is, of course, a second-tier problem. The priority concern should be the multi-layered, multi-pronged damage that privilege does to everyone else. But both concerns are interconnected.