An election year always brings a fresh crop of books earnestly warning against the perils of partisanship. The solution to this “problem,” these books usually suggest, is a kind of bland nonpartisan attitude — the Golden Meh.

This is a popular pose among pundits and op-ed columnists, one that seems to arise from an intense desire not to be disliked. The prescription of such pundits always seems to be that we mustn’t take our politics too seriously. If we take politics seriously, then we’ll want to try to get it right — thereby implying that others might be wrong, which might lead to all sorts of unpleasant disagreement. Such disagreement should be avoided, they advise, by floating above it all and never taking a clear stand one way or another. Ignore diversity of opinion and maybe it will just go away.

The high priests of nonpartisanship thus present a vision of the public square that resembles the excruciating awkwardness of Thanksgiving Dinner with relatives. Lots of small talk, evasion and denial, but no substance or conviction lest people start raising their voices in disagreement and spoiling the meal.

I don’t care for this proposed solution because I think it misrepresents and misunderstands the problem.

Partisanship is not the problem. Here in America, partisanship is necessary — the inevitably result of a democracy structured so as to produce a two-party system. There are other ways to structure democracy, and it can be fun to dream of how things like proportional representation or fusion could be incorporated to allow for something other than what Duverger’s Law produces here in the U.S. But right now, and for now, we’ve got a two-party system and participating in our democracy means taking sides.

No, of course that doesn’t mean taking sides mindlessly, uncritically or unquestioningly. But it means making a choice and taking responsibility for making that choice. That’s what self-government means — accepting responsibility for making the difficult, imperfect choices that government entails.

An “overcrowded genre” or sub-category of these election-year books is, as Tony Jones describes it, books “on how Christians of different political persuasions can nevertheless maintain faithful and congregational unity.”

Such books tend to earnestly remind us that Jesus is neither a Republican or a Democrat. Amen! And, also, No duh! Because Jesus doesn’t have to vote in the next election. I do. And my choice will be between a Republican and a Democrat. Jesus won’t be on the ballot.

Many of these books offer a Christian variation of the anti-partisan Golden Meh argument. Christians can “maintain faithful and congregational unity,” they suggest, by downplaying or denying political diversity. “The best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity,” they say, echoing Yeats without seeming to realize he wasn’t offering that as advice.

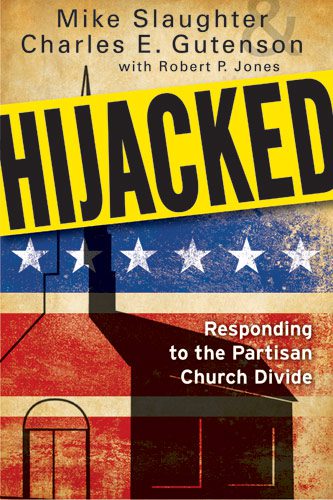

Happily, Mike Slaughter and Charles E. Gutenson have attempted something more ambitious and more constructive with their election-year book, Hijacked: Responding to the Partisan Church Divide.

Happily, Mike Slaughter and Charles E. Gutenson have attempted something more ambitious and more constructive with their election-year book, Hijacked: Responding to the Partisan Church Divide.

That subtitle conveys what sets this book apart from much of the genre. The real problem, the authors say, is not the partisanship, but the division.

In the strongest parts of this book, that focus is clear, and the authors offer many constructive suggestions for how to prevent political diversity and political distinctions from producing division in the faith community. In other places, that focus is shakier, with the authors occasionally following the partisans of nonpartisanship into treating partisan politics as the heart of the problem. That makes for an uneven argument, undermining and distracting from their firmer, central concern about not allowing political diversity to create a “church divide.”

Slaughter and Guterson write from a Methodist perspective, and at the center of their argument is a good, solid Methodist ideal: “In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, liberty; and in all things, charity.”

They work hard — and at times make the reader work hard — to locate political partisanship and political diversity in the realm of “non-essentials.” Such political convictions, they say, should not be made into a threat to or a condition for church unity. I think this is correct — but not absolute — and the authors’ discussion of why political stances should be regarded as distinct from the core essentials of doctrine is often insightful and helpful.

Most helpful, I think, is the fourth chapter, on “The Logic of Disagreement.” This is a thoughtful exploration of how Christians often fall into “conflating theology and ideology”:

Quite often, the first step involved with a partisan ideological position becoming intertwined with a theological or faith commitment is the belief by one political party or the other that such a combination can be exploited for partisan political gain. In other words, generally speaking, the engagement of the issue is not for the sake of the issue itself, but rather the perception that the issue can be aligned with faith in a way that encourages Christians to support that party because of the perceived conflation of the partisan issue with a particular faith commitment. We all are familiar with the term “wedge issue” — an issue that can be given enough priority that it will create a “wedge” to divide the voting patterns of a particular group in order to gain political support for our own group. …

For the strategy to work, however, the issue has to cease to be just an ideological issue and must, rather, come to be seen as a matter of faith — that is, religious faith and ideological commitment must become conflated. Ideally, this has to happen so thoroughly in the minds of the Christian group being targeted that they no longer take time to reflect on the matter. It simply is taken for granted that Christians must necessarily believe in this particular way on this particular issue. … Christian believers “must” believe in this way.

This chapter is very strong at tracing how this process unfolds on the side of “the Christian group being targeted.” Unfortunately, it doesn’t go as far in exploring who it is that is targeting the Christian group.

The passive-voice construction of “the Christian group being targeted” masks 30 years of American evangelical history. If evangelicals have been the object of that targeting, who was the subject? And why should those subjects have been allowed to “hijack” evangelical identity, reshaping a faith community into a voting bloc and even rewriting how those Christians go about reading their own Bibles?

Slaughter and Gutenson’s discussion of “The Logic of Disagreement” also clarifies what comes up short in their broader emphasis on “in essentials, unity.” In opposition to the well-funded political operatives manufacturing wedge issues, the authors argue that contingent political opinions ought not to be regarded as of equal importance with essential credal doctrines.

But for most American evangelical Christians, there’s no such thing as essential credal doctrines, because evangelicals don’t pay much attention to the creeds. Instead, evangelicals employ “statements of faith,” which tend to be much, much longer and more detailed than anything dreamed of at Nicea. And where the creeds focus on what we believe about God and about the church, these statements of faith are primarily focused on what we are required to believe about the Bible.

Specific partisan political stances are regarded as equal in importance to core doctrinal beliefs because those specific political stances are expressions of those core doctrinal beliefs. They function as a short-hand for the exhaustive claims about the Bible contained in those dense, multi-page statements of faith. Thus, in 2012 among American evangelicals, a statement of opposition to same-sex marriage or to legal abortion is meant to be synonymous with an affirmation that the Bible is the “inerrant, infallible Word of God.”

The conflation that Slaughter and Gutenson warn against is already a done deal. For many American evangelicals, it is already simply “taken for granted that Christians must necessarily believe in this particular way on this particular issue.”

What is taken for granted there is that this is what their inerrant, infallible Bibles obviously and unambiguously and unquestionably teach as central, pre-eminent doctrines. The Bible forbids legal abortion and civil rights for GLBT people. They simply know this to be true because everyone they know knows it to be true. This, for them, is what the Bible has come to be about.

“Hijacked” is a good word to describe what happened there. And I can’t help but hear it spoken in Denzel Washington’s voice: “You’ve been hijacked. You’ve been had. You’ve been took. You’ve been hoodwinked, bamboozled, led astray, run amok.”

Your Christian group has been targeted.