Nicolae: The Rise of Antichrist, pp. 66

When we last left Buck Williams, he was standing in the parking lot of his newsmagazine’s office, watching the bombs fall on Chicago.

I’m not clear exactly where this office is, but it seems to be in the suburbs somewhere — near enough to Chicago that their power goes out when the bombing begins, but far enough away that Buck and his co-workers feel comfortable “climbing atop their own cars to watch a huge aerial attack on the city.”

So the GCW staff don’t seem to think they’re in immediate danger, but they still have great seats to take in the spectacle of World War III.

Witnessing that aerial attack, Buck says exactly what you’d expect him to:

“Who’s got a cell phone I can borrow?” Buck shouted over the din in the parking lot. …

A woman next to him thrust one into his hands, and he was shocked to realize she was Verna Zee. “I need to make some long-distance calls,” he said quickly. “Can I skip all the codes and just pay you back?”

“Don’t worry about it, Cameron. Our little feud just got insignificant.”

Verna is right. Personal conflicts mean nothing now. Her lawsuit regarding Buck’s workplace intimidation and violence can wait. Chicago is under attack. The newsroom has been cut off without electricity. Only one thing matters now for journalists like Buck Williams and Verna Zee: How can we file this story?

Journalists, you have to understand, are first responders. And like all first responders, they have a duty and an instinct to run toward calamity. Police rush to restore order. Firefighters rush to rescue those in danger. EMTs rush to attend to the injured. And journalists rush to bear witness so that the public can know what is happening.

As it turns out, Buck and Verna are not really journalists. It never occurs to either of them that they need to be reporting any of this.

Nor does such a thought flicker for even a second across the minds of any of the other GCW staff there in the parking lot. None of them looks to Buck or to Verna — their bosses — for marching orders or assignments. None of the photographers even bothers to snap pictures of the view from there in the parking lot. After pausing for a moment to take in the sight of the third-biggest story any of them has ever witnessed, they all just wander off to their cars and head home.

The power’s out, after all, so the work-day must be over.

Buck never says a word to suggest that they might do otherwise. He doesn’t ask for volunteers to head into the city. He doesn’t set anyone to work to find an Internet connection or a backup power supply to let them begin reporting or broadcasting or printing. He never gives another thought to this job, just as he never gave another thought to any of his former colleagues in New York when that city was destroyed.*

“I need to borrow a car!” Buck shouted. But it quickly became clear that everyone was heading to their own places to check on loved ones and assess the damage. “How about a ride to Mt. Prospect?”

That paragraph is something of a break-through for Buck and for the authors, so let’s take a moment to celebrate this landmark moment in the series.

Something just happened that hasn’t happened before in these books. Buck doesn’t quite seem to realize it himself, but he’s just had an epiphany.

Once again, calamity has struck and once again Buck Williams is desperate to get home, to check on his loved ones and to assess the damage. But here, for the first time, Buck looks around and sees the other people around him. He suddenly realizes what he had never realized before — that calamity has struck them too and that, just like him, they also are desperate to get home, to check on their loved ones, and to assess the damage to their lives.

That didn’t occur to Buck early in the first book when the Event turned the world upside down. He raced across the rubble-strewn tarmac of O’Hare, viewing all the dazed and injured people around him as nothing more than obstacles in his path. Nor did it occur to him earlier in this book when O’Hare was destroyed and all the other cars rattled by the blast and fleeing along with him seemed to him as nothing more than traffic — more obstacles and not people just like him, trying just as he was to escape the destruction.

Yes, it’s a bit disappointing that this epiphany strikes Buck here only because he realizes that his urgent needs are not their priorities. He only sees their corresponding needs due to the inconvenience it entails for him.

But still, it’s progress.

“I’ll take you,” Verna muttered. “I don’t even want to see what’s happening in the other direction.”

“You live in the city, don’t you?” Buck said.

“I did until about five minutes ago,” Verna said.

“Maybe you got lucky.”

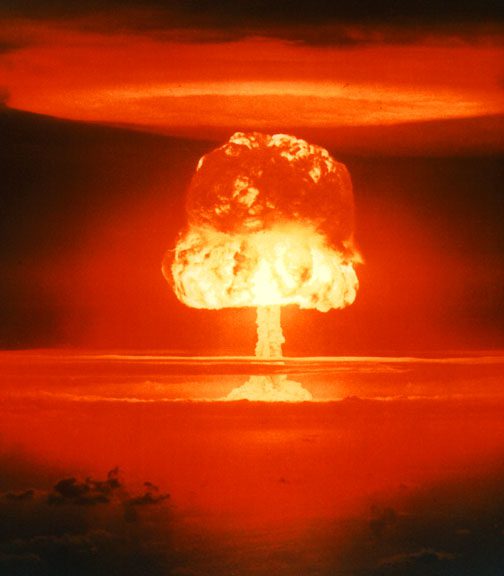

“Cameron, if that big blast was nuclear, none of us will last the week.”

Just like earlier, with the bombing of New York City and the airport, it seems the attack on downtown Chicago is employing perhaps-nuclear technology. At least with nuclear war you know where you stand, but the uncertainty that follows a perhaps-nuclear assault can be agonizing.

“I might know a place you can stay in Mt. Prospect,” Buck said.

“I’d be grateful,” she said.

Yep, Verna Zee is joining the gang, sort of. Her sudden transformation from cartoon workplace villain to sidekick might seem to strain plausibility, but then nothing about Jerry Jenkins’ portrayal of Verna so far has been at all plausible, so that’s not really a concern.

The important thing, though, is that readers don’t miss the lesson from this scene: Cities are dangerous places full of violence and lesbians. Stay in the suburbs and stay safe.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Three months from now, salvage workers in the ruins of Manhattan will find the body of Stanton Bailey. The former publisher of Global Weekly was fired when Nicolae Carpathia took over the magazine, renaming it Global Community Weekly and putting Buck Williams in charge of it as his puppet.

Bailey had certainly been rich enough to retire, but he was a newsman at heart and he couldn’t just sit by while the new global leader made every news outlet an official mouthpiece for the new global government. He’d funneled his retirement savings into an underground alternative newspaper. That is where he’d been, at the offices of that little outlaw rag, when the attack on New York City had begun.

His body was found near that of a photography intern, an off-duty firefighter, and the old woman the firefighter had rescued from a crumbling building after the first wave of bombing. All four were killed when the bombers returned and destroyed the entire block. On the dead intern’s camera, the salvage crew found pictures of the firefighter carrying the woman to the street.

The firefighter’s name was Richard Czerwinski. The woman’s name was Sondra Jefferson. Neither of them had any ID on them when their bodies were found, but their names had been written — with proper spelling carefully recorded — in a notebook found in Stanton Bailey’s left hand.

Buck Williams had been warned about the coming attacks on New York City, and he could have warned his old boss to get out of there before the bombing started. The authors don’t tell us why Buck never warned his friend, but I think I know. Stanton Bailey wasn’t Buck’s kind of journalist. He couldn’t be trusted with secrets the way Buck could be. If Buck had told Bailey what President Fitzhugh had told him, then you just know Bailey would have leaked that to the public.