Rules are a lousy way to get people to follow rules.

Just at the most basic level, giving rules and expecting them to be followed doesn’t work unless those rules are explained, understood and owned by the people you expect to follow them. No one will, or can, respect a rule that hasn’t been explained and understood.

So if you’re big on rules, or if you’re trying to make a career or a hobby out of scolding people for not following your rules, then it might be good to step back and consider whether you might be the source of this problem. If you haven’t explained your rules, or if you’re not able to explain your rules, then it’s pretty silly to expect anyone else to treat them with respect.

This is why our Christian Rules for Sex and our Rules for Christian Sex are a dead end. It’s not so much that these rules are widely disobeyed, but that they are largely irrelevant. We don’t bother explaining most of them. We aren’t able to explain many of them. So it shouldn’t be surprising that others don’t understand them either.

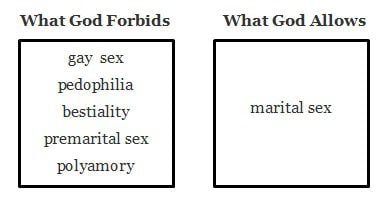

Part of the reason we don’t bother explaining these rules is that they seem so simple. The Christian Rules for Sex/Rules for Christian Sex seem to boil down to a single, binary question: Yes or no? Are we talking about sex between a married straight couple? If yes, the rules say, then everything is fine. If no, the rules say, then it is an abomination and a vile stench in the nostrils of God.

Part of the reason we don’t bother explaining these rules is that they seem so simple. The Christian Rules for Sex/Rules for Christian Sex seem to boil down to a single, binary question: Yes or no? Are we talking about sex between a married straight couple? If yes, the rules say, then everything is fine. If no, the rules say, then it is an abomination and a vile stench in the nostrils of God.

Libby Anne summarized this nicely in her “Tale of Two Boxes,” from which I’ve borrowed the illustration used here.

When the church teaches this binary question and the set of rules it provides as the whole of Christian teaching about sex it’s basically inviting people to ignore what it has to say. As long as such rules are asserted without being explained, explored and defended, then no one should ever expect them to be followed, honored or otherwise taken seriously. (And, no, citing chapter-and-verse is not a way of defending the rules, just of reasserting them.)

Now, I think that part of the reason this binary question and its collection of rules haven’t been explained and defended is because these rules, as usually asserted, can’t be explained or defended. I think our usual assumptions about the CRS/RCS are, in many ways, wrong.

This is where my more conservative evangelical critics accuse me of wanting to “do away with the rules” and of arguing that “anything goes.” That’s not true, but such accusations are to be expected from folks who have asserted and embraced a set of rules without exploring or explaining them, even to themselves.

My response to such accusations is always the same: I’m not saying anything goes, I simply want you to treat your “biblical rules about sex” exactly the same way that you’re already treating the biblical rules about money. I want you to take the exact same hermeneutical approach that you are already taking to every biblical teaching on wealth and possessions and apply that to biblical teaching on sexuality. Then treat both sets of teachings — and other people — with more respect than your current practice seems to do with regard to either subject.

My point here, though, is not to argue about the substance of the CRS/RCS, but to note that this rule-based approach is fundamentally misguided — that rules are just about the worst possible method for getting people to obey the rules.

Asserting and reasserting a list of rules rather than offering a functional sexual ethics won’t ever produce ethical behavior. All you’ll get from asserting a list of rules is a long list of people who break them.

This rules-based approach also has all kinds of disastrous unintended consequences. (At least, I hope these consequences are unintended.) Rod at Political Jesus outlines many of them in a righteous rant titled “India, Ohio, John Piper, Religion and the Triumph of Rape Culture.”

His focus there is on how the “purity culture” of American Christianity feeds and fosters the rape culture of American Christianity. (Yes, the rape culture of American Christianity. When the church is noticeably different from the rest of American culture on this point, then we can start talking about “the rape culture of American society surrounding the church.” But we’re nowhere near that yet.)

Rod says, bluntly, that it’s time for America’s Christian subculture to “kiss purity culture goodbye”:

In the Old and New Testament, purity and religion are never separate from seeking justice from others. Religious purity according to James 1:27, “Religion that is pure and undefiled before God, the Father, is this: to care for orphans and widows in their distress, and to keep oneself unstained by the world” shows an understanding of purification that is not limited to sexual purity.

What complementarians (church going men who see women as 2nd class citizens) cling to is exactly what is impure: the power that men have over women.

He also links to several other excellent posts elsewhere on this same subject of purity culture as a way of enforcing men’s power over women, including Sarah Moon on the Orwellian logic of “complementarianism,” E.J. Graff’s powerful, disturbing essay, “Purity Culture Is Rape Culture,” and a killer post from Wartburg Watch on John Piper and Domestic Violence (about which, see also the latest from Dianna Anderson).

I want to highlight in particular a post from Julia at Women in Theology on “Sexual violence and the church: talking to teens.” After some wise words on what needs to be taught to teens, and how to teach it, Julia concludes with an important explanation of why sexual ethics is better than sexual rules — and the cruel consequences of the rules-based teaching that predominates in our churches:

The reality of sexual violence is important to discuss and teens, like the rest of us, need to hear that it is a very serious sin. Yes, sin. The churches have language to bring to this discussion that secular society does not. We can talk about gravely harmful behavior without having to resort to legal definitions and loopholes. We can claim that sexual activities, in every instance, should embody love and respect for oneself and the other. The language of sexual activities as an expression of love and respect clearly exposes the misstep that a rape victim could ever be “asking for it” and the mistake of defining consent exclusively in terms of its minimum requirements. It is important that we keep talking about sexual violence in church.

Julia sees theological language as an asset in teaching sexual ethics, and she employs such language forcefully.

Yet she also shows how the mere assertion of rules — X is sin, don’t do X — isn’t just unhelpful, but harmful. It contributes to the victim-blaming that allows the triumph of rape culture Rod discusses.