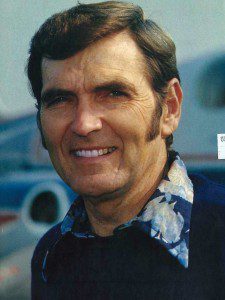

Throughout his decades-long career, Tim LaHaye has always been three things: an entrepreneur, an evangelist, and a right-wing political activist. If you want to understand LaHaye, the role he played in creating and expanding the religious right, and his ongoing influence on American culture, then you need to appreciate all three of those things and the way they are bound together, inseparably, in LaHaye’s long life.

Steve Fouse provides a valuable service by illustrating each of those three things in his lengthy profile: “Tim LaHaye, the Bible Belt, and the Sun Belt: More Complex Than Kansas.” Fouse has done an enormous amount of research, but almost all of it was from the stacks, not from the shelves. His essay avoids the many books written about LaHaye’s politicized theology/theologized politics, and focuses, instead, on newspaper mentions of LaHaye over the years. Fouse even avoids LaHaye’s own books, mentioning them only in the context of how they are mentioned by others in the press.

That’s an odd, but interesting, approach. It provides a sometimes-illuminating new angle from which to view LaHaye’s work and influence. Fouse has done a terrific job ferreting out more than a dozen disparate press reports on LaHaye’s various endeavors and it’s great to have that all assembled in one place. This will be a helpful reference for future writers exploring the legacy of LaHaye, of the religious right, and of the “Bible prophecy” political theology of premillennial dispensationalism.

Unfortunately, Fouse doesn’t try to tie all of this together. His thesis actually prevents him from doing so, as his goal in discussing LaHaye is to show that the “Sun Belt” religion represented by the Orange County evangelist is “more complex” than the simpler portrait of “Bible Belt” religion provided by Thomas Frank in What’s the Matter With Kansas? (Fouse cites Frank’s book only as mediated through Darren Dochuk’s From Bible Belt to Sun Belt — the only book directly cited in the piece.)

So really this profile of Tim LaHaye isn’t primarily a profile at all. It’s an attempt to marshal data points demonstrating this purported “complexity” — to show that the white suburban evangelicalism exemplified by LaHaye’s career can’t fit into the categories Frank used to describe the white rural evangelicalism of Kansas. (Fouse doesn’t ever actually use the word “white,” though. He doesn’t seem to notice that this is a defining, limiting aspect of both the Bible Belt and Sun Belt religion he is discussing. That’s kind of a huge problem, as we’ll discuss in a bit.)

Fouse is uncomfortable with the way Frank seems to portray Bible Belt Christians as “reactionary, helpless, and stupid.” Me too. But rather than challenge that, he basically argues that, yes, the white Southern Christians may be “reactionary, helpless, and stupid,” but the white suburban Christians are more sophisticated — as demonstrated by the work of LaHaye:

LaHaye and fellow conservative evangelicals are indeed concerned about key social issues like abortion and gay rights. These issues are not, though, the only issues of concern to them. Of early and key importance to LaHaye and others was the protection and promotion of marriage and family. Evangelicals were not just interested in preventing gays from marrying, but were also interested in strengthening their own marriages and protecting their children from what they saw as harmful and untrue forces at work in schools and society, including feminism and sex education. The threat of communism and socialism loomed large in their minds and promised to wreck the economy and destroy the country they wanted to preserve for their children. The issues they voted on and the stances they promoted were many, and conservative evangelicals were proactive in building organizations and recruiting others to their causes. These were not the reactionary, helpless, and stupid conservatives of Kansas; these were generating, agential, and coordinated conservatives of Southern California. Their scope was not just their immediate area and cities, but extended to the entire nation, and had particular influence among Bible Belt evangelicals. These conservatives didn’t just tend their farms and hope for conservatism to change the world; they build businesses, crafted numerous organizations, and traveled the country and the world espousing their views trying to steer their country toward a future for which they hoped. To some extent, they succeeded. They ousted liberals from Congress and seated one of their own in the White House. Their time in the spotlight may have come and gone, but they were undeniably a major political force in the 60s, 70s, and 80s.

That’s the core of Fouse’s argument, and the core of his confusion. He wants to suggest that white SoCal evangelicals are more “complex” than white Bible Belt evangelicals because “abortion and gay rights” are “not … the only issues of concern to them.” They’re also interested in “the protection and promotion of marriage and family.” That confuses a new euphemism for the same agenda with a new agenda.

It’s probably easier to understand Fouse’s confusion if we look at Beverly LaHaye, Tim’s wife of 65 years. Fouse mentions Beverly LaHaye’s campaign in the 1970s “to defeat the Equal Rights Amendment.” He doesn’t mention how that effort led to her founding Concerned Women for America — a lobbying and direct-mail fundraising group with more than 250,000 members and an annual budget of $8 million. Concerned Women was founded in reaction against the ERA as a kind of anti-National Organization for Women.

Using the logic of Fouse’s argument, we could say that Concerned Women has a “complex” agenda. The group didn’t only oppose the Equal Rights Amendment, it also opposed no-fault divorce and government-funded child care. See? Complex.

But that supposed complexity only seems complicated if we fail or refuse to see how all those things are the same thing. Concerned Women is anti-feminist and anti-modern. It advocates for patriarchal, sectarian hegemony. That advocacy is multi-faceted, but not terribly “complex.”

This is just as true of Tim LaHaye and his white “Sun Belt” political theology. All the supposed “complexity” that Fouse attributes to it falls under this same general rubric — which applies just as well to the white “Bible Belt” political theology of Kansas and the South. It’s anti-feminist and anti-modern. It advocates for patriarchal, sectarian hegemony. Their opposition to “abortion and gay rights” are expressions of this. Their understanding of “the protection and promotion of marriage and family” are expressions of this. That’s why, for example, opposing universal public child care is a consistent piece of the religious-right agenda and not the contradiction of “pro-life” and “pro-family” claims that it would otherwise seem to be.

All of which is to say that Fouse’s thesis is profoundly confused. But don’t let that stop you from reading the entire article, because if you bracket the pure hooey of that “complexity” argument, the long stream of details Fouse provides from LaHaye’s ever-evolving entrepreneurial activism offers a fascinating look at the way the religious right has adapted, developed and expanded over the years.

That entrepreneurial approach is as inseparable from LaHaye’s political activism as his right-wing theology is from his right-wing politics. LaHaye’s response to any perceived political problem is to start a new organization. Some of those have been lucrative successes. Others have been lucrative failures. They’ve all been geared toward raising money to deploy power. And toward deploying power to raise money. (The chicken-or-egg question of which matters most isn’t important.)

Here’s a classic example of that:

In the late 70s, LaHaye and other evangelical conservatives banded together in support of Proposition 6, a ban on gays and lesbians serving as teachers, and Proposition 13, a limit on property tax. Homosexuality served as a hot topic politically and did much to rally evangelical conservatives to political action. Lacking great public support even from Ronald Reagan, Proposition 6 failed. Nevertheless, homosexuality continued to be a strong point of contention for conservative voters. With the failure of Proposition 6 fresh on his mind, LaHaye was motivated to start the Californians for Biblical Morality, a political action group designed to encourage politicians to ‘“make laws and decisions based on traditional biblical morality.’”

… The Associated Press also ran a national article highlighting the activities of Californians for Biblical Morality against the ACLU. The article mentions that LaHaye started CBM just a few months before Jerry Falwell started the Moral Majority. Curtis Maynard, an associate minister at Scott Memorial Baptist Church and the interviewee for the article, says that Moral Majority is “[CBM’s] nationwide counterpart.” The article mentions CBM’s political opponents as “’humanists’ … espousing atheism, evolution, amorality, self-centered autonomy and socialism” and their allies as those promoting “anti-abortion laws and amendments permitting prayer in public schools and against pornography.”

Tim LaHaye founded CBM the same year that Beverly LaHaye founded Concerned Women. And they both used the same method, following the blueprint laid out by LaHaye’s buddy Richard Viguerie, the direct-mail fundraising guru who was the architect for so much of the religious right. Bev LaHaye campaigned against the ERA, creating a huge database of names and addresses that formed the basis for founding Concerned Women. Tim LaHaye campaigned for an anti-gay proposition in California, creating a huge database of names and addresses that formed the basis for founding Californians for Biblical Morality.

Proposition 6 did not pass, but it was still a success, because it identified the base of funders for CBM — tens of thousands of names and addresses of people who have demonstrated that they’re scared enough to write checks when confronted with the terrifying prospect of gay teachers in the schools. Or of “evolution, amorality, self-centered autonomy and socialism.” Or of secular humanists opposed to official sectarian prayers.

And they provided a list of potential new audiences for ever-m0re Bible prophecy seminars and seminars on “the protection and promotion of marriage and family.”

The lucrative seminar business and the checks from donors to “Californians for Biblical Morality” helped to fund the next round of big political campaigns and petition drives. And those would, in turn, supply thousands of new names and addresses for the entrepreneurial evangelist’s next new organization.

Fouse’s article provides a nice round-up of LaHaye’s relentless founding of institutions — some of which he spun off into thriving, ongoing enterprises, while others quickly faded to be just as quickly replaced by the next new thing. The Institution for Creation Research, unfortunately, is in the former category. As is the Council for National Policy:

With his mentorship, Southern California evangelicals created the Council for National Policy. This extensive and secretive umbrella organization united four hundred evangelical leaders, 84 percent of whom [are] from the Deep South. More than any other previous organization, the Council for National Policy united virtually every major evangelical leader, including LaHaye, James Dobson, Bill Bright, and many more.

That claim about “every major evangelical leader” is not an overstatement — not so long as you limit the category, as Fouse does there, to include only white, right-wing men. Most of those major evangelical leaders, Fouse notes, citing Dochuk, are Southern “Bible Belt” evangelicals. LaHaye’s Council for National Policy has helped to unite and coordinate their political action, keeping them lined up in support of his far-right political agenda. That sounds an awful lot like what Thomas Frank describes in What’s the Matter With Kansas? (As does the way the anti-gay religious folk supporting Prop 6 above were exploited to help pass the anti-tax Prop 13 — a classic example of Frank’s thesis.)

Here’s Fouse’s conclusion:

In a way, Tim LaHaye typifies post-war conservative evangelicals. LaHaye entered the scene eager to combat social and political ills as he saw them, and his modus operandi was to band together with other conservatives in political action groups, or to start a new political action group with explicit goals. In the 60s and 70s LaHaye’s fame and influence grew, swelling well beyond Southern California, showing rippling influence with fellow conservative evangelicals in the Bible Belt and drawing notice throughout the country and the world. By the 1980s, with Reagan in the White House, conservatives seem to fracture, with ministers like LaHaye now combating fellow evangelicals on social and political stances. …

That’s pretty sharp, until the next sentence:

LaHaye seems to fade from political power around that time, moving to the background and creating a popular fictional series that had little or no political effect.

The idea that “moving to the background” indicates a lessening of political influence is backwards. Some power is wielded in the spotlight, but “the background” is often where the real power lies. LaHaye knows this, which is why his CNP has wielded more influence for a longer time than most of the many spotlight-hungry organizations that have come and gone since it began.

The notion that LaHaye’s “popular fictional series … had little or no political effect” is wrong on at least two levels. First of all, it’s factually incorrect, because the series has had enormous political effect. LaHaye’s “prophecy”-obsessed PMD theology continues to shape American politics in numerous ways — foreign policy in the Middle East, a reflexive suspicion of international cooperation, conspiracy-driven opposition to gun safety or climate regulation, etc.

And just consider this: from 1995 through 2007, Tim LaHaye co-authored a series of runaway best-sellers steeped in John Birch Society ideology. During those years he sold more than 60 million copies of books that served as propaganda for a particular political agenda. The tea party movement sprang up in 2009, espousing the exact neo-Bircher ideology and agenda promoted in LaHaye’s novels. Is that just a remarkable coincidence?

The second mistake in that sentence above is that Fouse misunderstands what he has already revealed about the subject of this profile/not-profile piece. In the preceding paragraphs, Fouse shows us that Tim LaHaye is always starting new entrepreneurial endeavors. The Left Behind books are part of this pattern. Tim LaHaye cranked out a fiction series for the same reason he started CBM or the CNP or the ICR: to advance his politico-theological agenda, and to provide the revenue that will fund the next organization, campaign, proposition or institute. That’s who he is and what he does.

Whether it’s a new book, a new direct-mail fundraising group, a single-issue lobbying effort, a series of novels, a movie, or whatever, each new start-up enterprise is about influence and revenue. The Left Behind series has provided Tim LaHaye with plenty of both.