World-class athletes from all over the globe had gathered in a great American city for a storied competition steeped in tradition, harmony and international good will. And then a madman set off a bomb, killing two people and injuring more than a hundred others.

It’s worth remembering the Centennial Olympic Park bombing this week, as the parallels between that attack and the horror Monday in Boston may help to provide some perspective as we once again experience the shock, sadness and anger in response to such senseless violence.

I couldn’t help but remember the 1996 attack yesterday as I listened to numerous reports confirming that organizers would, indeed, continue to hold the Boston Marathon, or that participants would, indeed, return to race again in future years. I don’t recall hearing any other possibility even considered in the aftermath of the 1996 attack. Maybe I’ve just forgotten and reporters back then were seriously considering the possibility that the 2000 Summer Games in Sydney would be cancelled in surrender to this cowardly act, but I don’t remember anyone then actually entertaining such capitulation as an option worth talking about.

Along those lines, these are some wise words from security expert Bruce Schneier:

Terrorism is a crime against the mind. What happened in Boston, horrific as it is, is theater to make you scared. That’s the point.

… To the extent this terrorist attack succeeds has very little do with the attack itself. It’s all about our reaction. We must refuse to be terrorized. Imagine if the bombs were found and moved at the last second, and no one died, but everyone was just as scared. The terrorists would have succeeded anyway. If you are scared, they win. If you refuse to be scared, they lose, no matter how much carnage they commit.

If Schneier is right — and I believe he is — then maybe in a way it’s a good thing that so many commentators and reporters this week have described the Boston attack as “unprecedented,” as though the Centennial Park bombing never happened. In a sense, that shows that we were not permanently scarred or changed by the Atlanta attack. And thus that we do not need to be permanently scarred and changed by this more recent attack. We can, as Schneier says, choose not to surrender to the violence of the violent.

But then maybe we’re not so much resilient as we are shallow and narcissistic. Maybe each successive incident wipes away all memory of previous ones because we’re so enthralled with the momentary sense of vicarious significance each new one provides — each one another opportunity to excite ourselves with the notion that we are living in “the most critical time in the history of the world.”

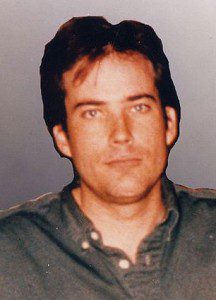

One lesson from the 1996 attack that we don’t seem to have learned is not to jump to conclusions before we’re certain of who was responsible. Security guard Richard Jewell — who discovered the bomb and saved lived by helping to move the crowd away — was falsely implicated in the Atlanta bombing, but few seem to take that as a lesson to avoid speculation, guesswork and rushing to judgment before the facts are known.

The mistaken focus on Jewell allowed the actual bomber — Eric Rudolph — to escape into the wind, eluding capture until 2003.

And remembering Rudolph points out another important lesson from the 1996 attack: We must always beware the temptation to demonize others and to puff ourselves up. That might feel good, but some others may not be able to understand that it’s all just a game. Denouncing the “murderous” baby-killing Holocaust and fantasizing that we, the noble champions opposing it, are the moral heirs of the great abolitionists is all just puffery and pretense American Christians use to make believe we’re distinguishable from our neighbors. But the danger of talk like that is that someone like Eric Rudolph might come along and take it seriously.