God was finally going to believe

in a man both good and strong,

but good and strong

are still two different men.

— Wislawa Szymborska, “The Century’s Decline”

Yesterday, National Public Radio’s All Things Considered had a segment debating U.S. involvement in the Syrian civil war: “Analysts Divided on U.S. Arming Syrian Rebels.”

The guests were two people I wasn’t familiar with: Andrew Tabler, “senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy,” and Joshua Landis, “who directs the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma.”

Landis argued that the U.S. should avoid getting entangled in the Syrian war because he doesn’t think this is a problem that America can solve:

I think the United States should stay out of this. This is a civil war, ethnic civil war, which America cannot adjudicate and we can’t solve. The Syrians ultimately have to figure out who they are, if they can live together and what their national identity is going to be. And if America jumps into the middle of it, we’re going to want to kill the extremists and we’re going to want to destroy the Assad regime and we’re going to be fighting a two-front war in Syria.

And we’re not going to get the outcomes we want and we’re going to spend a fortune doing it. And, you know, there’s got to be one of these wars we just don’t get involved in.

Tabler, on the other hand, is urging the U.S. to begin arming the rebels in Syria, and he’s disappointed that America didn’t get involved sooner:

If it had occurred earlier, it would have been easier, but unfortunately, now we have more extremists who have moved into different areas that are controlled by the opposition. So you can’t guarantee that every bullet would not make it into the hands of an extremist.

But overall, you could strengthen the mainline nationalist local and franchise battalions and it would help deal them back in. And the reason why I still think that’s a good idea, you know, with groups that we vetted and we can work with is because I just don’t think this conflict is going to end any time soon.

By the end of the segment, this disagreement got pretty nasty — in a very familiar way:

LANDIS: Could I have one rejoinder? Andrew just said that I’m a regime-supporter for making this argument and therefore trying to scare Americans away. I think that’s an unfair accusation. I’m an American.

TABLER: You’ve got to be kidding, Josh. You have been one of the biggest supporters of Bashar al-Assad for a long time, and look, that’s your position. And I think the argument you make…

LANDIS: That’s completely untrue. And I’m an American trying to keep us out of another Iraq-type of venture.

TABLER: I think that you are…

LANDIS: What you are saying is that Syria’s not like Iraq.

TABLER: I’m sorry I don’t agree with you.

LANDIS: And Syria’s exactly like Iraq. This is not about the regime. This is about America staying out of a quagmire, Andrew.

TABLER: Josh, I just think that your positions have come consistently on side of the regime.

It’s like a trip back in time to 2003.

Andrew Tabler is trying to revive one of the nastiest, most illogical of all the nasty, illogical arguments that misled America into the disastrous invasion and occupation of Iraq. He’s repeating Glenn Reynolds’ ugly, foolish slur that anyone who opposed invading Iraq was “objectively pro-Saddam.”

This accusation doesn’t make any more sense in 2013 than it did a decade ago, but I think I’ve finally figured out why people like Reynolds and Tabler trick themselves into thinking it does.

They’re not really talking about foreign policy. They’re talking about theodicy. They’re making a theological claim, with the United States in the role of God.

“Theodicy” refers to the problem of evil. I like Archibald MacLeish’s pithy summary of that problem in JB:

If God is God, He is not good,

If God is good, He is not God.

JB is a modern retelling of the story of Job, but MacLeish doesn’t have any better answers than the author of Job did. Here are the two seemingly incompatible ideas that story tries to reconcile:

1. God is “the Almighty,” or — as theologians say — “omnipotent.”

2. God is good (just, fair, loving, righteous, benevolent, etc.).

Now consider any evil, unjust, painful, horrible incident or context. Any will do, and you have an infinite array of choices: the Lisbon earthquake, the Boxing Day tsunami, 9/11, childhood leukemia, AIDS, a car crash, a drive-by shooting, tyranny, calamity, pain, disease, flood, famine — take your pick.

The existence of any or all of those seems to suggest that God cannot be both omnipotent and good. A God that was both omnipotent and good ought to have intervened to stop such horrors, or to reverse them. That’s what any of us would do if it were in our power to do so, even those of us who make no claim to be anything like as good as the ultimate goodness we attribute to God.

The existence of any or all of those seems to suggest that God cannot be both omnipotent and good. A God that was both omnipotent and good ought to have intervened to stop such horrors, or to reverse them. That’s what any of us would do if it were in our power to do so, even those of us who make no claim to be anything like as good as the ultimate goodness we attribute to God.

The claim of God’s goodness makes such intervention necessary. The claim of God’s omnipotence means that such intervention would be guaranteed to succeed. The relentlessly evident lack of such divine intervention therefore suggests that one or the other of these attributes of God is wrongly attributed. Either an all-powerful God could intervene to prevent injustice, suffering and evil, but chooses not to — and is therefore not good. Or else a good God wants to intervene to prevent injustice, suffering and evil, but is unable to do so — and is therefore not all-powerful.

That’s the conundrum. (I would say that’s the crux of the problem, but the literal crux of the matter is something else entirely.)

I think the illogical logic of the Neo-conservative “objectively pro-Saddam” argument comes from taking this framework of theodicy and applying it to American foreign policy. In the framework of theodicy, goodness always entails an obligation to intervene. Interventionist foreign policy draws on that, I think. For interventionists, America is good and therefore America must intervene.

From this view, the evil, horror and injustice of the Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq — like every evil, horror and injustice — demanded an active response. Wouldn’t you have put a stop to it if it were within your power to do so? Of course you would have. And thus the U.S. was obliged to invade Iraq, because with its unrivaled military might, the U.S. did have the power to do so.

This isn’t a military or strategic argument. Nor is it a discussion of just-war theology. It’s an analogy from theodicy. Either the mighty U.S. could intervene to prevent injustice, suffering and evil in Iraq, but chooses not to — and is therefore objectively pro-Saddam. Or else the U.S. wants to intervene to prevent injustice, suffering and evil, but is unable to do so — and is therefore not mighty enough and needs to further increase the Pentagon’s budget.

The dilemma of theodicy has two horns — ultimate goodness and ultimate power. Both of those are problematic in this analogy. But here let’s set aside the problem of trying to equate the U.S. with ultimate goodness. And let’s set aside as well the host of other troubling factors, like the seemingly arbitrary choice of elevating one particular unjust context above all others as uniquely requiring intervention. Here let’s just focus on the simple and obvious fact that the United States military, while quite powerful, is not omnipotent.

I don’t simply mean that U.S. military firepower is finite, rather than infinite. That’s obviously true, but it’s not really the problem with this analogy.

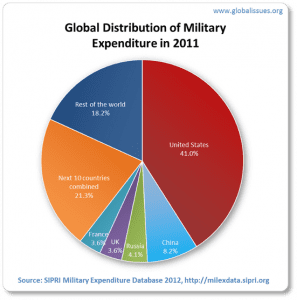

The United States spends more on its military than any other country. It’s not even close. American politicians love to boast of the nation’s military prowess, and they’re not wrong. The U.S. has more and better weapons than any other nation on the planet. So even though U.S. military firepower is finite and limited, it’s so far beyond that of most potential military foes that those limits don’t matter much. America’s nuclear arsenal could destroy the entire planet several times over. If you can kill everyone on earth more than once, it hardly matters that you’re unable to kill them all an infinite number of times.

The main reason that the U.S. military is not omnipotent is that it’s military might is only that: military might. The U.S. military cannot cure cancer, end a drought or feed the starving millions. The U.S. military can solve only those problems that are exclusively military problems. And it can address the military aspects of problems that are partly made up of military aspects — but only those military aspects. It cannot solve every problem or correct every injustice.

To put it crudely, the U.S. military is very, very good at killing people. But many problems — most problems, actually — can’t be resolved by killing people. Some few, perhaps, can. The vast majority cannot.

That reveals the confusion of our interventionist friends when they make the leap from theodicy to foreign policy. The idea they draw from the discussion of theodicy is that goodness requires intervention — that to be good means one is obliged to intervene against evil, suffering and injustice. I think that’s right, but it does not mean that one is obliged to intervene by killing people. It does not mean that this specific form of intervention is the only specific form of intervention called for — or that it is the best, or the first, or the most effective form of intervention.

Just-war theory addresses this in at least two ways. One is the principle of last resort, which says that military intervention and the use of military force must never be used unless everything else has been fully and legitimately tried first. The second is the principle of “reasonable hope.” That doesn’t mainly have to do with the prospects for military victory, but rather with the question of whether or not such a victory would likely produce a just outcome. (Generals often understand the wisdom of this better than civilians do.)

Those two principles are among the most ignored and sorely abused of the entire “just-war” school. I think that’s true mainly because we spend so much money and time preparing for war that we’re unable or unwilling to imagine other, prior resorts — other ways of intervening that would likely have a more reasonable hope of achieving a just and desirable outcome.