A couple weeks ago we looked at a helpful short post from Danny Coleman in which he discussed the anxious conflict gnawing at many Christians who are reluctantly convinced that obedience to God’s Law requires them to be unkind, unjust and unloving to LGBT people. Coleman pithily describes those Christians’ dilemma:

They do not hate or fear LBGT people. They fear God. They carry a perception of the wrathful Old Testament God who will destroy cities or nations if “sin” is found in the camp. … Attempts to reconcile this ancient God of wrath with the God of love and inclusion that Jesus represented tend to create a sort of cognitive and spiritual dissonance. And so, most Christians don’t hate and fear gays — they really want to love them. What they fear is God’s wrath and what they hate is the idea of the destruction God will bring down if LGBT people are accepted — if “sin” is allowed.

The problem is that even for Christians bound by such a stunted view of sin, conscience says something else. Conscience tells them that even if they don’t feel fear or hatred, behaving as if they fear or hate others is still wrong. So they feel trapped — torn between the conflicting demands of conscience and “obedience.” If they avoid the guilt of sinful disobedience by allowing “sinful” others in the camp, they incur the guilt of mistreating those others. Conscience pulls them toward love of the other; “obedience” pulls them in the other direction.

You can see the enormous strain of this being-pulled-apart in a recent guest-post by Peter Wehner at Tim Dalrymple’s blog on Patheos’ evangelical channel. The post, titled “An Evangelical Christian Looks at Homosexuality,”* reveals Wehner’s struggle to reconcile the tug of conscience with what he perceives as the demands of obedience. He begins by stating that “I’d associate myself with the views of Timothy J. Keller, senior pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City,” linking to a recent discussion in which Keller inadvertently restated, endorsed and underlined the point Danny Coleman made above. Keller said:

If you say to everybody, “Anyone who thinks homosexuality is a sin is a bigot,” [Jonathan Rauch] says, “You are going to have to ask them to completely disassemble the way in which they read the Bible.” Completely disassemble their whole approach to authority. You are basically going to have to ask them to completely kick their entire faith out the door.

That, in a nutshell, is the fear Coleman describes. And it is the fear that pervades Wehner’s argument.

But Wehner is also more honest than Keller. Keller pretends as though the accusation of bigotry arises solely from the belief that “homosexuality is a sin.” Wehner recognizes that, in reality, the accusation of bigotry arises from Christian support for legally enforced bigotry. He seems to recognize that the problem is not so much that Christians like himself believe “homosexuality is a sin,” but rather that this belief has led many such Christians to deny full legal equality to LGBT people. I am an enthusiastic, almost obsessive, coffee-drinker. I don’t think Mormons are bigots because they regard drinking coffee as a kind of sin. But if the Saints suddenly lost their minds and began lobbying for laws denying coffee-drinkers like myself the right to marry, or insisting that it should be legal for employers to fire coffee-drinkers, then, yes, that would be bigotry.

But Wehner is also more honest than Keller. Keller pretends as though the accusation of bigotry arises solely from the belief that “homosexuality is a sin.” Wehner recognizes that, in reality, the accusation of bigotry arises from Christian support for legally enforced bigotry. He seems to recognize that the problem is not so much that Christians like himself believe “homosexuality is a sin,” but rather that this belief has led many such Christians to deny full legal equality to LGBT people. I am an enthusiastic, almost obsessive, coffee-drinker. I don’t think Mormons are bigots because they regard drinking coffee as a kind of sin. But if the Saints suddenly lost their minds and began lobbying for laws denying coffee-drinkers like myself the right to marry, or insisting that it should be legal for employers to fire coffee-drinkers, then, yes, that would be bigotry.

Wehner doesn’t explicitly call out Keller for the self-serving disingenuousness of his “Anyone who thinks homosexuality is a sin” straw-man nonsense, but I give Wehner credit for acknowledging the legitimate substance of the complaints about anti-gay bigotry. The main thrust of his argument is to challenge that substance without challenging the belief he shares with Keller, that homosexuality is a sin.

Wehner’s conclusion isn’t wholly conclusive. He seems extremely cautious not to be perceived as advocating “disobedience” lest he incur the wrath of God or of the tribal gatekeepers of evangelicalism. But he’s clearly pointing toward a solution that I think can work for conservative evangelicals like Wehner or Keller or Dalrymple. They don’t need to change their theology or their hermeneutics in order to stop denying other people full legal equality and civil rights:

I think it’s reasonable to say that even for orthodox Christians,** how the Scriptural injunctions against homosexual behavior should manifest themselves in modern American law and society are not self-evident. For example, you might believe homosexual conduct is not what God intended but (like idolatry) that view should not be written in law.

I’d be quite pleased if more anti-gay Christians would settle on that view. (Keller calls this a “Neo-Anabaptist” position, but really it’s just plain Baptist — more Roger Williams than John Howard Yoder.)

My main point here, though, is not the conclusion of Wehner’s argument or the logic he uses in getting there. What strikes me more is the impulse compelling him to make this anguished argument — which, again, is the strain of being pulled in opposite directions by the demands of conscience and the demands of “obedience.” For Wehner, as for many white evangelicals, “their whole approach to authority” compels them to believe that God demands a “firm stance” opposing homosexuality. Yet Wehner’s conscience is pulling him the other way — he seems to genuinely regret the harm that is being done to LGBT people by Christians who advocate laws denying their civil rights.

The pangs of conscience are clearest toward the end of Wehner’s post, when he recalls a conversation with former InterVarsity president Steve Hayner:

“I doubt whether God will have much to say about our political convictions in the end,” Steve said to me, “but I’m quite sure that he will have something to say about how we loved the least, the marginalized, the outcasts, the lonely, the abused — even when some think that they have it all. Political convictions that lead toward redemption and reconciliation are most likely headed in the right direction.”

Hayner describes a trajectory leading “toward redemption and reconciliation” and emphasizing the powerless, “the outcasts, the lonely, the abused.” And Wehner says, “It seems to me there is great wisdom in his words.”

It seems that way to me, too. But I should warn Wehner that the gatekeepers of the white evangelical tribe don’t look kindly on anyone who allows this wisdom to shape their hermeneutic. That, they say, would be disobedient. It would “ask them to completely disassemble the way in which they read the Bible. Completely disassemble their whole approach to authority.” You’d be asking them to kick their faith out the door and they’d prefer, instead, to kick you out of the tribe.

Just ask Steve Chalke. Chalke’s evangelical credentials were beyond question — even more than Keller’s or Wehner’s or Dalrymple’s. But he was judged to have headed too far “in the right direction” of reconciliation and love for the outcast, and he was banished from the evangelical tribe — cast into the outer darkness with the mainliners, the “progressives” and the Episcopalians.

But here’s the joyous thing that Steve Chalke discovered. He’s not anguished. He’s not torn between conscience and obedience. For Chalke, obedience to God and conscience are pulling in the same direction. That unity of direction is at the root of the meaning of the word “integrity,” which is why Chalke’s farewell letter to the tribal gatekeepers — his manifesto in support of marriage equality — was titled, “A Matter of Integrity: The Church, sexuality, inclusion and an open conversation.”

When conscience and obedience are integrated — when they are pulling in the same direction — then faith becomes something that perpetually challenges us to become better people. It calls us to constantly expand our love and our capacity for love and to move ever onward, ever outward and ever Christward.

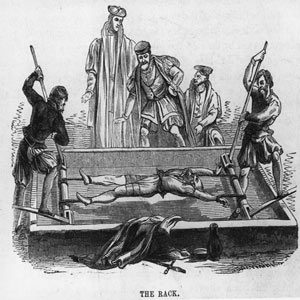

Peter Wehner is clearly aware of the discomfort and anxiety that comes from the kind of faith Danny Coleman described and Tim Keller endorsed — a form of faith in which conscience and obedience are at odds, pulling in opposite directions. It’s like being stretched on a rack. And, one way or the other, such faith will always entail being racked with guilt.

Maybe Steve Chalke is right. Maybe God is a better person than you think. Maybe obedience to what God wants doesn’t have to produce a queasy, uneasy conscience and the nagging sense that treating others unkindly and unfairly is still wrong, even when it’s done out of a sincere attempt to be obedient.

I’ve experience both forms of faith — the fearful kind Coleman describes and the fearless sort Steve Chalke advocates. The latter is a lot more joyful.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* I had a hard time getting past that title, which seems like the archetypal headline for any in-group discussion of out-group people. You could fill a bookshelf with the unspoken assumptions packed into and conveyed by those six words: An Evangelical Christian Looks at Homosexuality.

Here are some potential alternate versions of that title:

• “A Member of the Tribe Observes Outsiders.”

• “I am a legitimate person. You are an issue and an abstraction.”

• “The Myopia of Privilege.”

• “Jonah looks at the Ninevites.”

• “Blessed are you, Lord our God, Ruler of the Universe, who has not made me a homosexual.”

• “Even the dogs eat the crumbs that fall from their masters’ table. And you’re welcome.”

That actual title — “An Evangelical Christian Looks at Homosexuality” — includes something of all of those, and more. And that’s before we even consider the false assumption that “an evangelical Christian” must, by definition, be looking at homosexuality from the outside — that no evangelicals are LGBT and no LGBT persons are evangelicals. (Here are links to more than a dozen blogs written by people who are both.)

While there’s something of that attitude pervading the whole post, the general spirit of Wehner’s piece is better than that title.

In general, though, I’m way beyond tired of articles and blog posts titled “An Evangelical Christian Looks at …” It’s long past time for a new wave of articles titled, instead, “An Evangelical Christian Listens to …”

** The colloquial use of “begs the question” to mean “raises the question” leaves us without a term for what Wehner is doing here. “Orthodox Christians,” he says, are those who believe the Bible declares homosexuality to be a sin. And we know that the Bible says so because this is what “orthodox Christians” say the Bible says. He’s assuming the initial point. Or presuming it, actually.