Travis Loller’s Associated Press piece, “Churches Changing Bylaws After Gay Marriage Ruling” offers a decent overview of how some local congregations who have implicitly opposed marriage equality are now making sure this isn’t just an unwritten rule, but a part of their explicit policy.

That’s a legitimate concern for faith-based non-profits, schools and other agencies who want to practice religious-based employment discrimination — they need to get that down in writing as an explicit religious conviction. But it’s unnecessary for churches imagining some nonexistent threat of the government telling them who they can and cannot marry. The right of religious institutions to marry or not marry as they see fit has always been, and remains, unquestioned and unchallenged. (Divorced Catholics looking to remarry, for example, can’t hope to take their local Catholic church to court to force the local priest to bless their wedding. And I couldn’t sue the local synagogue for refusing to allow me to marry there because I’m not Jewish.)

That’s a legitimate concern for faith-based non-profits, schools and other agencies who want to practice religious-based employment discrimination — they need to get that down in writing as an explicit religious conviction. But it’s unnecessary for churches imagining some nonexistent threat of the government telling them who they can and cannot marry. The right of religious institutions to marry or not marry as they see fit has always been, and remains, unquestioned and unchallenged. (Divorced Catholics looking to remarry, for example, can’t hope to take their local Catholic church to court to force the local priest to bless their wedding. And I couldn’t sue the local synagogue for refusing to allow me to marry there because I’m not Jewish.)

Loller notes that the panic leading to some of this rewriting of marriage bylaws is unfounded. But, of course, being an AP reporter, he can’t just supply those corrective facts. He has to do so in “he said/she said” style by attributing them to the “other side.”

“Critics, including some gay Christian leaders, argue that the changes amount to a solution looking for a problem,” Loller writes in the same way that AP reporters always write things like, “Critics, including some scientists who have studied the matter, argue that the Earth is not flat.”

Still, though, this may be a useful exercise for some churches. Attempting to articulate their implicit beliefs as a formal policy requires them to examine and justify those beliefs in a way they may have avoided doing previously:

In more hierarchical denominations, like the Roman Catholic Church or the United Methodist Church, individual churches are bound by the policies of the larger denomination. But nondenominational churches and those loosely affiliated with more established groups often individually decide how to address social issues such as gay marriage.

Eric Rassbach is an attorney with the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a public interest legal group that defends the free expression rights of all faiths. He said it is unlikely the government would try to force a pastor to perform a same-sex marriage, but churches that rent out their facilities to the general public could face problems if they refuse to rent to gay couples.

Although his organization has not advocated it, he said it could strengthen a church’s legal position to adopt a statement explaining its beliefs about marriage.

Rassbach is right that it is “unlikely the government would try to force a pastor to perform a same-sex marriage” — although “unlikely” seems a bit understated for something so pointless, illegal and unprecedented. We could also, I suppose, say it was “unlikely” that the government would force churches to baptize unbelievers. Or that it was “unlikely” that the government will mandate conversion to a particular religious sect. Those statements would be true as well if we use “unlikely” in the Rassbachian sense of utterly impossible.

Justin Lee is the reality-based “some critic” Loller allows to speak in lieu of reporting fact as fact:

“They seem to be under the impression that there is this huge movement with the goal of forcing them to perform ceremonies that violate their freedom of religion,” said Justin Lee, executive director of the Gay Christian Network, a nonprofit that provides support for gay Christians and their friends and families and encourages churches to be more welcoming.

“If anyone tried to force a church to perform a ceremony against their will, I would be the first person to stand up in that church’s defense.”

Loller also allows some unnamed attorneys to correct the misimpression otherwise reinforced by this article:

Some denominations are less concerned about the Supreme Court rulings. The Assemblies of God, the group of churches comprising the world’s largest Pentecostal denomination, sought legal advice after the rulings. An attorney for the group distributed a memo to ministers saying there was no reason to change their bylaws.

But what fascinated me most in this article was Loller’s conclusion, which captures the way the culture is knocking at the door of the church, leaving many in it perplexed:

The bylaw changes are coming at a time when many churches are wrestling with gay marriage in general and are working hard to be more welcoming to gays and lesbians.

“It’s probably one of the most difficult issues our churches are facing right now,” said Doug Anderson, a national coordinator with the evangelical Vineyard Church. “It’s almost an impossible situation to reconcile what’s going on in our culture, and our whole theology of welcoming and loving people, versus what it says in the Bible.”

Poor Doug Anderson can’t reconcile this “impossible situation” because he’s constructed it as irreconcilable. He’s created a contrast and a contradiction, and now he despairs of any way to resolve it.

Just look at that phrase: “Our whole theology of welcoming and loving people versus what it says in the Bible.”

Where does that “versus” come from? Anderson’s “theology of welcoming and loving people” is “what it says in the Bible.” That’s where the command to welcome and love people — all people — comes from.

But doesn’t the Bible also say that some people must be excluded? Yes, it does. It says that we mustn’t welcome foreigners or the uncircumcised or the unclean. It says that in many places, you can look it up. But it also says the opposite.

So how can we “reconcile” this “impossible situation” in which we have the Bible versus the Bible? Well, for Bible-based believers like Anderson, maybe it would be good to look to the Bible. How does the Bible itself reconcile these conflicting demands of the Bible?

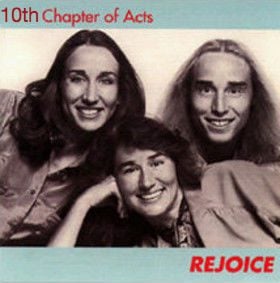

Anderson, in other words, is in very much the same bewildered state that the apostle Peter was in the story in Acts chapter 10. “Peter was greatly puzzled about what to make of the vision that he had seen,” Acts says.

In that vision, he had been shown all kinds of unclean food and God had commanded him to eat it. It was “almost an impossible situation to reconcile” that command “versus what it says in the Bible.”

And that’s when a bunch of unclean Gentiles knocked at his door. That’s when “what’s going on in our culture” forced Peter to resolve his impossible situation. He accompanied those unclean outsiders back to a house filled with even more unclean outsiders — the very people “the Bible says” he was forbidden to associate with. That was, in fact, the first thing he said to them: “The Bible says I’m not allowed to go near you.” (“You yourselves know that it is unlawful for a Jew to associate with or to visit a Gentile.”)

“But …”

But the next word Peter says is “but.”

“The Bible says one thing, but …”

That’s terrifying for folks like poor Doug Anderson. They revere the Bible as their authority, their lifeline and lifeblood. And so, for them, if “the Bible says” we must never say “but.” If “it is unlawful” then it is unlawful no matter what else the Bible says about a whole theology of welcoming and loving people.

Who are we to question what “the Bible says”? Who are we to think that it could ever be acceptable for us to say, “The Bible says one thing, but …“?

But here’s the thing: “The Bible says one thing, but …” is something the Bible says.

Throwing off the shackles of clobber texts that force us to contradict love is biblical.