None of us wants to end up there — “on the wrong side of history.” We don’t want to think that the ideas or values we’re supporting today will wind up almost universally recognized as false, wrong and destructive by those who come after us.

But on the other hand, none of us can say, with complete certainty, how history will come to regard our time. And, by definition, no one can ever enjoy any actual benefit from the potential future consolation of “being on the right side of history.” By that point, we’ll be long gone. For that matter, no one can ever experience any actual penalty from the potential future condemnation of “being on the wrong side of history.”

That’s why appeals to “the wrong side of history” can’t help resolve any disputes in the here and now. It’s a wager that neither side will live to have to pay or to get to collect.

Better, then, to heed the wisdom of the Sermon on the Mount: “Today’s trouble is enough for today.”

Better, then, to heed the wisdom of the Sermon on the Mount: “Today’s trouble is enough for today.”

So instead of worrying about whether or not we might one day be regarded as “on the wrong side of history,” we should concern ourselves with whether or not we are, today, on the right side in history. And the important thing to remember about being on the right side in history is that it’s not always — or usually — the same thing as the winning side.

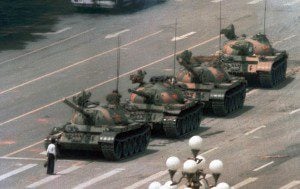

Think of Tank Man in Tianenmen Square. He was on the right side of history. He was on the right side in history. But his side in history and of history didn’t win. Not yet anyway, almost 30 years later.

That gap — the gap between the side that was in the right in history and the side that seems to have won — is part of why we need to talk so much about the “right side of history.” We want to believe that the right side and the winning side will ultimately turn out to be the same side. We want to believe that although the arc of the moral universe may be long, “it bends toward justice.”

That’s a phrase associated with Martin Luther King Jr., of course. Last week was marked by a host of commemorations and remembrances of King surrounding the 50th anniversary of his “I Have a Dream” speech during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

King was on the right side in history. The hagiography and near-universal acclaim he received on that 50th anniversary shows that we all can now admit that he was on the right side of history. It’s still not clear, though, whether King was on the winning side. His dream of “Jobs and Freedom” for all remains elusive.

The 50th anniversary of the march and of King’s great speech also provided a clearer picture of what it means to have been on “the wrong side of history.” Those who had been on King’s side in King’s day had an easier time of it on the anniversary. They could proudly recall and reproduce their memories of the 1963 march.

The Christian Century reached back into its archives to republish its editorials and reporting from before, during and after the March for Jobs and Freedom. The New Republic was able to do the same. Those magazines were able to celebrate both the anniversary itself and their own coverage of it. They could celebrate their own history because they had been on “the right side of history.”

We didn’t see a similar celebration from, for example, The National Review — which aggressively opposed King and the march in 1963. Or from Christianity Today, which timidly, cautiously, “moderately” avoided taking sides. Alas, not taking sides doesn’t turn out to be an effective way of avoiding being on “the wrong side of history.”

But again, what matters most today is not who was on the right or wrong side 50 years ago. What matters most today is whether or not we are ourselves, today, on the right side in history.

Problem is that it’s unlikely we will be able to assess the present honestly until we’re willing to do the same for the past.

That’s what’s dangerous about so much of the revisionist distortions we saw last week from those who felt obliged to celebrate Dr. King even though they opposed his March for Jobs and Freedom in 1963 and even though they continue to oppose his ideals of Jobs and Freedom in 2013.

Consider, for example, the attempt by several conservative culture warriors to claim that Martin Luther King Jr. would support their opposition to LGBT equality. People actually said this on the 50th anniversary of a march designed and organized by MLK’s great friend and mentor, Bayard Rustin. Rustin, who taught King the practice and strategy of nonviolent resistance, was openly gay in the 1950s (and thereby also taught King — and the rest of us — quite a bit about courage).

Or consider white culture-warrior Gary Bauer, who tried to use the anniversary to conscript King’s moral authority to serve the anti-feminist side of the war on women. Bauer claimed King would have supported his crusade against Planned Parenthood — that’s a transparent lie and an audacious attempt to rewrite reality.

Such lies don’t just distort the past, they distort the present. To face the present honestly requires that we be honest about the past as well. Only then can we determine, today, whether or not we’re fighting on the right side in history.

Let me give the last word here to Mark Kleiman, who addresses the conservatives of today who want to claim King and his legacy as somehow supporting their agenda:

Martin Luther King died while on a campaign to support a public-sector labor union. You’re entitled to say that he was a bad man and a Communist, as your faction did while he was alive, and that his assassination was the natural result of his use of civil disobedience, which is what Ronald Reagan said at the time. You’re entitled to say that he was a great man but that his thoughts are no longer applicable to the current political situation. But what you’re not entitled to do is to pretend that, if he were alive today, MLK would not be fighting against you and everything you stand for. He would.