Earlier this year McDonald’s created a publicity backlash for itself by creating a “personal finance” website for its employees.

Like much of the personal finance industry, the site was a mixture of banal common sense, condescension and victim-blaming. Worst of all was the sample household budget that the site offered as a model for McDonald’s workers. That budget wound up shining a huge spotlight on the fact that all the site’s preachy moralizing about frugality and “personal responsibility” didn’t mean bupkis to fast-food wage-slaves earning minimum wage. The budget included ridiculously unrealistic monthly figures — like $600 for rent, $20 for health insurance, and $0 for heat — yet it still assumed a 60-hour work week at two different jobs in order to make the math possible.

Oh, and it also left out taxes — pretending that McDonald’s workers earning $8.50 and hour were taking home $8.50 an hour. Otherwise change that 60 hours to 80 hours.

Laura Northrup at The Consumerist summed it up:

This is a terrible budget. Besides leaving out gas, heat, car maintenance, and remotely realistic medical expenses, it leaves out clothes, entertainment, furniture, various kinds of personal hygiene, furniture, charitable and religious giving, cleaning supplies, and groceries. Groceries.

It also completely ignores that you might have children, which is convenient, because it’s hard to fit child care for those 60 hours a week that you’re working into this budget. Assuming that you can even get that many hours from your job: maybe it’s time to start looking for a third one.

The bottom line is that “Whoever wrote these materials had no grasp of what it’s actually like to live on $8 or so per hour.”

Because of that, much of what the site offers that might otherwise seem like common-sense advice about making responsible “choices” reads instead as simply clueless. The authors of the site don’t realize that McDonald’s low-wage workers have no choice but to make such “choices.” They’re already forgoing all of those “luxuries” not out of choice, but out of necessity.

Lecturing people about their choices when their context does not afford them any is not just stupid, it’s cruel.

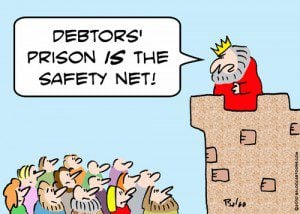

Which brings us to Dave Ramsey, the Christian-ish personal finance guru who has built an empire off of just such stupid and cruel lecturing. That McDonald’s website offered a distillation of Ramsey’s ideology of “personal responsibility” as the only significant variable for financial security.

Which brings us to Dave Ramsey, the Christian-ish personal finance guru who has built an empire off of just such stupid and cruel lecturing. That McDonald’s website offered a distillation of Ramsey’s ideology of “personal responsibility” as the only significant variable for financial security.

McDonald’s didn’t design that website itself, mind you. They contracted that out to Visa. Yes, that Visa — the credit-card company. Dave Ramsey is famous for preaching against debt and borrowing. Visa makes its living encouraging debt and borrowing. Isn’t it interesting, then, that the essence of their “personal finance” advice turns out to be indistinguishable?

Sure, it’d be bad for Visa if suddenly everyone started following Ramsey’s advice, paying for everything with cash up-front, but Visa doesn’t seem too worried about that. They’re far too delighted by the larger effect of Ramsey’s influence: A three-hour daily radio show in every major market preaching that it’s a moral duty to make your payments on time and that it’s an irresponsible shirking of your personal moral duty to question interest rates or inexplicable fees. The anti-debt preacher may pose as their enemy, but they think of him as their MVP.

Credit-card banks and other lenders are scared of Richard Cordray and of Elizabeth Warren. But they’re not scared of Dave Ramsey. They love the guy. No matter how many new ways they concoct to fleece their customers, they can always count on Ramsey to have their back, telling his radio audience that it’s their fault and that their only response should be to cut expenses and pay those new rates and fees in full.

We’re seeing an encouraging wave of push-back against Ramsey’s victim-blaming and his apparent ignorance of “what it’s actually like to live on $8 or so per hour.” I want to highlight some of the sharp responses to Ramsey’s mean poverty-is-your-fault ideology, the graceless works-righteousness behind his individualistic misunderstanding of “personal responsibility,” and the way his victim-scolding framework serves the interests of creditors and robber barons. We’ll get to a bunch of them in Part 2, but here I want to focus on one in particular: Helaine Olen’s long, detailed profile and critique for Pacific Standard, “The Prophet.”

Olen knows this world intimately. She used to be a “personal finance” columnist and then became a whistleblower on the whole charade, publishing Pound Foolish: Exposing the Personal Finance Industry.

Here’s Olen’s stark summary of Dave Ramsey’s advice:

- Purge yourself of debt;

- Live on cash;

- Pretend economic trends don’t affect you;

- Blame yourself when they do.

This admonition to blame no one but yourself appeals most to those who are, in fact, largely powerless:

In [Ramsey’s] version of the story, the wider economy’s problems are not structural or political, but instead stem from the fact that most people, including his listeners, are weak-willed, self-indulgent, and stupid (he doesn’t shy from the word) when it comes to spending. “The problem with your money,” he often says with perfect certainty, “is the person in your mirror.” Once you get over the casual meanness of this message, it becomes clear how oddly reassuring it is. It assumes that we are in control. To his listeners, Ramsey holds out the promise that they can simply choose to be different — that it’s within their power to not take part in recessions and the economic troubles facing American families.

And that, like the McDonald’s budget, requires that we prefer an imaginary world in which, “there is always fat that can be trimmed from a family’s budget, always another job that can be scraped together to add to a family’s income.”

Olen discusses the importance of Ramsey’s personal story as a redemption parable for his audience, but also notes how it distorts his understanding of what the real world is really like for people whose stories aren’t just exactly like his was:

His story begins during the real estate boom of the 1980s. As a young entrepreneur fresh out of college, he convinced a local Tennessee bank to loan him money so he could build up a real estate empire. But Ramsey’s properties were financed via short-term loans and lines of credit. The bank called in all the debts, and his $4 million real estate portfolio collapsed. Lawsuits and foreclosures ensued.

… Ramsey was a risk-prone real estate developer who went bankrupt because he attempted to leverage borrowed money into riches and failed. He didn’t hit financial bottom because he was fired, or because he was stuck with a high-deductible, low-benefit insurance policy when his child got sick.

There seems to be, in other words, an element of projection in Ramsey’s “personal responsibility” shtick. He imagines he knows how everyone else got into debt because he knows how he did — through extravagance and risk and leveraged dreams. That taught him one set of lessons that might apply to other people whose story is just like his story, but those lessons are completely alien and irrelevant to someone who got laid off or who got hit by a drunken driver.

He also, defensively, denies his followers access to the actual way he first achieved his own debt-free status: Ramsey declared personal bankruptcy in 1988. Sure, his methods have helped him stay debt-free since then, but bankruptcy protection is how he got there in the first place.

Olen also examines the huge fortune Ramsey has amassed from doling out his victim-blaming message of “tough love”:

As the world economy was imploding in 2008, Dave Ramsey went shopping for a new home. According to published reports, Ramsey paid a little more than $1.5 million for several acres of land in Franklin, Tennessee, and then constructed a 13,000-plus-square-foot residence (the garage is another 1,450 square feet). After completion, it was valued at just under $5 million. More than a few evangelicals thought Ramsey was flaunting his wealth, and took to the blogosphere to say so.

The attention seems to have gotten under Ramsey’s skin. “No one was mad at me when I sold 10 books and made $10,” he said during his Houston show. “Wait ’til you sell 10 million — you’ll be attacked like you wouldn’t believe.” He laments that “winning is no longer OK” in our culture.

He’s a “winner,” see. What does that make people who don’t own $5 million homes? Losers. And like all sore winners, there’s nothing Ramsey hates more than losers. He’s not just thin-skinned and prickly about his own prodigal lifestyle, he’s also deeply resentful of those who have less than he does:

Not surprisingly, Ramsey’s political views — which are often vividly on display during his radio show and in his public appearances — are quite conservative. He argues that estate taxes are “immoral” and a sign of incipient socialism. So too is Obamacare, which will damage the American economy. Social Security is “running out of money fast” and “mathematically doomed.” And he believes the federal government, like any household he advises, needs to say “no” to things it can’t afford, balance its budget, and stop borrowing money. (Needless to say, he’s generally not in favor of raising taxes either.)

What’s more, Ramsey has said that the story of rising income inequality in America — a story backed up by reams of data — is “not really true.”

Dave Ramsey serves up a lot of lies in the quotations there above. Well, let’s be generous — Ramsey says many things that are not true. Ramsey says many things that are not true that he ought to know are not true. Ramsey says many things that are not true that are so easily disproved that it would seem impossible for anyone to continue repeating them unless that person was simply unconcerned with whether or not they are true.

So maybe not a liar, then. Maybe just a lazily ignorant fellow with a reckless disregard for the veracity of what comes out of his mouth.

In the middle of her article, Helaine Olen discusses the Bible verse — or the half-verse — that Dave Ramsey has taken as his slogan and marketing motto:

He turned to the Bible, where he saw wisdom in Proverbs 22:7. A portion of that verse is his mantra to this day: “The borrower is the slave of the lender.” (The first part of the verse — “The rich rule over the poor” — is less prominently featured in his messaging.)

Ramsey’s message to borrowers is to work their way to emancipation from the slavery of debt. It is not the slave’s place to question the legitimacy of their enslavement. For Ramsey, Proverbs 22:7b always carries with it an implicit citation of Ephesians 6:5: “Slaves, obey your earthly masters with fear and trembling, in singleness of heart.”

“The rich rule over the poor” because the rich are winners. Maybe lazy, irresponsible poor people think that “winning is no longer OK,” but Ramsey knows that winning means winning the right to rule, and to demand that your slaves make their payments on time, in full, without ever questioning your right to collect them.

Preaching this anti-Jubilee interpretation of Proverbs 22:7 means that Dave Ramsey had better hope that Proverbs 22:8 isn’t telling us the truth: “Whoever sows injustice will reap calamity.”