We’ve learned a lot about our ancestors in the past six months — even if much of what we learned was that we’ve still got a lot to learn. Here are just a handful of recent stories that have, or may have, big implications for our understanding of human origins.

Item No. 1: Five skulls — all 1.7 to 1.8 million years old — have now been recovered from a single site in Dmanisi, in the mountains of Georgia (the country by the Black Sea, not the state in the American south). The collection — young and old, male and female, all in remarkable condition — gives us an unprecedented look at the variation within that species, which in turn allows us to reconsider some of the other examples of such variation and whether some of those various specimens might not actually be from various species.

Adam Van Arsdale, one of the researchers who helped uncover these skulls, blogged about “The new (wonderful) Dmanisi skull.” Joel Duff has a nice post exploring how such ancient skulls came to be preserved in rock in such good shape. And as with all big science news, there’s also the overhyped headlines and the reminders not to get carried away by the hype.

Item No. 2: Scientists sequenced the genome of a Denisovan toe-bone and found out it was actually a Neanderthal toe-bone — despite being found in a cave in the Siberian region that gave the Denisovans their name. That freezing cave turns out to be a terrific DNA-storage facility, providing more detailed information about this ancient relative than we’ve previously been able to extract. This showed that Neanderthals and Denisovans and Homo sapiens all interbred — along with, perhaps, another as-yet-undiscovered ancient relative.

“What it begins to suggest is that we’re looking at a Lord of the Rings-type world — that there were many hominid populations,” says Mark Thomas, an evolutionary geneticist at University College London.

Item No. 3: That as-yet-undiscovered other relative is not to be confused with the Sima de los Huesos people, another group whose 400,000-year-old remains were found in Spain. The fragmentary DNA scientists were able to gather from a thigh-bone found there raises all kinds of new questions, as Carl Zimmer reported for The New York Times:

Scientists … retrieved ancient human DNA from a fossil dating back about 400,000 years, shattering the previous record of 100,000 years.

The fossil, a thigh bone found in Spain, had previously seemed to many experts to belong to a forerunner of Neanderthals. But its DNA tells a very different story. It most closely resembles DNA from an enigmatic lineage of humans known as Denisovans. Until now, Denisovans were known only from DNA retrieved from 80,000-year-old remains in Siberia, 4,000 miles east of where the new DNA was found.

In a longer discussion on his blog, Zimmer sums up where all of this seems to be pointing:

The combined evidence from fossils and DNA suggests that Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo sapiens share an ancestor that lived in Africa about 500,000 years ago. Our ancestors stayed in Africa while the ancestors of Denisovans and Neanderthals moved out to Europe and Asia. Homo sapiens evolved in Africa about 200,000 years ago, and then humans expanded out of Africa 60,000 years ago, after which they interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans. So, yes, many people on Earth today are have direct ancestors that were Neanderthals. Some have direct ancestors that were Denisovans. But in both cases, most of these people’s ancestors were Homo sapiens.

This new DNA (or, rather, this really old DNA) is from long before Neanderthals and Denisovans made contact with humans – but probably after their ancestors split from ours.

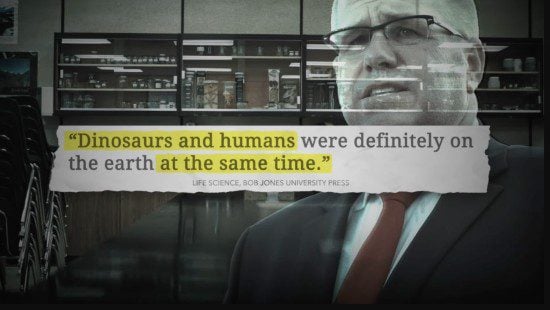

Item No. 4: At the Evangelical Theological Society meeting in Baltimore, Philip Ryken — a college president — spoke on the subject “We Cannot Understand the World or Our Faith without a Real, Historical Adam.” The sound you hear is every professor in the biology, geology, anthropology and biblical studies departments at Wheaton updating their résumé and looking around for a lifeboat.