I recently quoted, commended and amen-ed Richard Beck’s 2013 discussion of “Christian a/theism.” That led to a good question in comments: “Then… why are you a Christian at all?”

In seconding Beck’s perspective, I noted that all he’s really doing is providing a summary of the almost absurdly repetitive biblical argument of 1 John, just in fancier words. Here, again, is Beck:

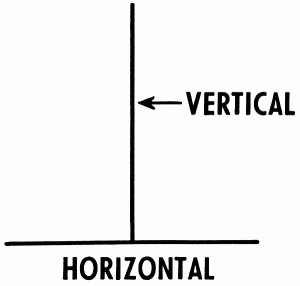

A common move in Christian a/theism is to collapse the transcendent into the immanent. That is, the vertical dimension where humans reach toward heaven and God is collapsed into the horizontal dimension where we reach toward other human beings. In a sense, the two dimensions become conflated, an identity relationship is formed. To love God is to love your neighbor. With no remainder. Those are the same thing.

I’m very happy with this move. In fact, I argue for something very much like this in Unclean. When push comes to shove if you ask me what loving God means I’ll respond with “loving your neighbor.” In fact, I’d go on to argue that when the two become decoupled — when loving God is pursued independently of loving your neighbor — we create the ingredients for the most toxic aspect of religion: loving God against your neighbor.

And here is whoever it was who wrote 1 John:

Beloved, let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love. God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world so that we might live through him. In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins. Beloved, since God loved us so much, we also ought to love one another. No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God lives in us, and his love is perfected in us.

… God is love, and those who abide in love abide in God, and God abides in them. Love has been perfected among us in this: that we may have boldness on the day of judgment, because as he is, so are we in this world. There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear; for fear has to do with punishment, and whoever fears has not reached perfection in love. We love because he first loved us. Those who say, “I love God,” and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen.

That is, bluntly, “an identity relationship.” That means, explicitly, “To love God is to love your neighbor. With no remainder. Those are the same thing.”

And it warns us against seeking the transcendent as something other than or superior to the immanent. It says that such a thing is impossible, and calls those who claim such a thing “liars.”

The first two sentences of that passage above — 1 John 4:7 and 8 — may be familiar to you if you grew up in an evangelical church in America. Those verses in the King James Version are the lyrics to a popular Sunday school chorus:

We sang this a lot at my church and school (in a slightly less danceable rendition than the reggae version above): ”

“Beloved, let us love one another: for love is of God; and every one that loveth is born of God, and knoweth God. He that loveth not knoweth not God; for God is love. Beloved, let us love one another.” And then, that odd little coda where we’d sing the reference: “First John four, seven and eight.”

That coda was necessary, I think. Without that citation and its reminder that these are words directly from the Bible we’d never have been allowed to sing such a chorus. After all, it sounds suspiciously liberal and Pelagian, doesn’t it?

I think that passage from 1 John underscores the validity of the question, “Then … why are you a Christian at all?” After all, like Jesus’ parable of the sheep and the goats, the author of 1 John seems to dismiss all religious claims, replacing them with the simple reality of whether or not one loves in deed as well as in word. “Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.” It doesn’t matter if you think you know God or if you say you know God — if you do not love, you know nothing. And also “everyone who loves is born of God and knows God.” It doesn’t matter if you think you don’t know God — if you love others, then you do, because that is what “knowing God” means. Those are the same thing. With no remainder.

I think that passage from 1 John underscores the validity of the question, “Then … why are you a Christian at all?” After all, like Jesus’ parable of the sheep and the goats, the author of 1 John seems to dismiss all religious claims, replacing them with the simple reality of whether or not one loves in deed as well as in word. “Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.” It doesn’t matter if you think you know God or if you say you know God — if you do not love, you know nothing. And also “everyone who loves is born of God and knows God.” It doesn’t matter if you think you don’t know God — if you love others, then you do, because that is what “knowing God” means. Those are the same thing. With no remainder.

So why not just get busy loving one another and not bother with the God stuff at all? As Richard Beck suggests, and I agree, that’s a fine approach. It avoids the very real peril of becoming the kind of liars who claim to love God while failing to love our neighbors and, thus, become guilty of hating both.

As 1 John says, “no one has ever seen God.” But we can see each other. It makes sense to focus on loving those we can see. It makes sense to focus on the immanent because that’s what we are — and where we are and who we are.

Yet 1 John also offers us this: “We love because he first loved us.” And that, for me, is part of my answer to “Why are you a Christian at all?”

Another part of the answer is this: “God’s love was revealed among us in this way: God sent his only Son into the world.” No one has ever seen God, but God’s love was revealed among us. Among us — not to us, dictated in a text, but among us, sent “into the world.” The very expression of divine love, 1 John is saying, was an act of the transcendent becoming immanent. Incarnation. That is the example we have been given to follow.

We have been shown what God looks like, 1 John says, in Jesus. And we have been shown what love looks like, also in Jesus — “for God is love.”

That is what and who I believe, and that is why I am a Christian. That is also why it’s not of great importance to me whether or not you or I or anyone else identifies as a Christian. “Everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.”