Broadly speaking, young-Earth creationists offer four different versions of that mumbling reply to the problem of telescopes. They’re worth looking at, briefly, because each reveals something about the character of these folks and of their ideology.

1. Deny, deny, deny.

If the vast distances of space are a visible rebuttal of creationist claims about the age of the universe, then the simplest thing for creationists to do is to deny that such vast distances exist. If just looking up at the night sky threatens your ideology, then don’t look up. If the heavens declare the glory of God in a way that doesn’t allow you to control and contain that glory, then don’t allow the heavens to declare anything.

A friend of mine attended a private Christian “school” in central Fracksylvania that taught an extreme form of this denial. An adult employed by that school, bearing the ludicrously inappropriate title of “science teacher,” explained to students there that stars are actually much smaller and much, much closer than those lying secular-humanist scientists claim. This “science teacher” even cited biblical support for this claim — suggesting that this was what the (King James) Bible meant wherever it referred to the stars as “lesser lights.”

A somewhat less extreme form of this denialism focuses on the methodology that astronomers use to measure the distance to very distant objects in the observable universe. Astronomy is actually extremely precise when it comes to such measurements up to about 500 light years, but it gets a lot trickier and more complicated when considering the mind-boggling distances beyond that. So some creationists happily concede that, yes, Sirius is, in fact, 8.6 light years away, and Aldebaran is, in fact, 65 light years away, but then they challenge and deny and derail every step and every variable of the calculations involved in determining the distance of any objects farther away than the 6,000 or 7,000 years they’ll allow for the age of the universe.

This is pretty much the same strategy creationists take in denying carbon dating methods. It allows them to string together lots of science-y words and thus to sound vaguely scientific, but it leads to some spectacular nonsense.

Just consider, for example, the claim that the Andromeda Galaxy is not 2.5 million light years away from the Earth, but only something less than 6,000 light years away. And also less than 6,000 light years across. I’m not an astronomer, so I can’t calculate the exact size of the explosion that would result from placing all of the stars of the Andromeda Galaxy and all of the stars of the Milky Way Galaxy within such close proximity, but I’m pretty sure that the only calculation needed to disprove this creationist theory is pointing out that we’re not all dead already.

2. The Omphalos hypothesis.

“Omphalos” is a Greek word for belly button. If Adam and Eve were created as fully grown adults — complete with belly buttons — then it seems that God likewise created the entire universe fully grown, complete with apparent evidence of a birth it never actually experienced.

The Omphalos theory claims a hidden “reality” that cannot be discerned from the appearance of the universe. Appearance and reality, it says, are separate and contradictory. There’s a weird elegance to that, in that such a theory can never be falsified or disproved — either by logic or by counter-evidence. (This is a theory that was designed to feed on counter-evidence.) But just as the claim that God created an apparently ancient universe a mere 6,000 years ago cannot be disproved, so too the claim that God created an apparently ancient universe a mere five minutes ago cannot be disproved. Thus another mocking nickname for this theory: “Last Thursday-ism.”

The benefit of Last Thursday-ism is that it allows its adherents to do credible science. They are free to study the apparent laws of the apparent universe, accepting its apparent age and all of the apparent implications of the apparent fossil record, the apparent cosmic evolution apparently seen through telescopes, and all of the apparent evidence of apparent geology, apparent biology, apparent astronomy, etc. Apart from that stipulation that everything we can observe or measure is but a dream within a dream, they can go about science just the same as any other scientist.

The ugly downside of this approach is that it makes God out to be a liar. Not an apparent liar, but a gleeful, deliberate deceiver.

While most Christians who believe in a young universe would balk at the idea of God sneakily burying Trilobite fossils all over the place in order to trick future paleontologists, they’re more inclined to embrace an Omphalos hypothesis explanation for the light from distant stars. Sure, that’s another form of divine deception, but it’s a pretty one. Maybe God just wanted us to be able to enjoy a night sky full of stars and so, on the fourth day of Genesis 1, God created all those stars and galaxies and nebulae with their light already reaching our sky here on Earth.

3. Some day, all of this science will be proved false.

The most vocal proponent of this theory is Southern Baptist blogger and seminary-destroyer Al Mohler. If science ever seems to contradict his interpretation of the Bible, Mohler says, then the science must be wrong, because his interpretation of the Bible is unquestionably right.

(Well, that’s what Mohler means, but he of course never speaks of his interpretation of the Bible. He just talks about the Bible as the authoritative, inerrant, infallible synonym of his interpretation of it. For Mohler, there is no such thing as the Bible apart from his interpretation of it.)

We just have to have faith, Mohler says. Have faith in [his interpretation of] the Bible and trust that [his interpretation of] it is true even when all of modern science seems to disprove [his interpretation of] it. After all, science is always changing. Just recently, for example, a new study suggested that the Black Death spread too quickly to have been borne mainly by fleas and rats. The new study suggests it must have been airborne. Scientists used to be so arrogantly confident in telling us all that the plague was spread by rats and fleas, and now all of a sudden they’re claiming something different. Those same arrogant scientists now seem so confident in claiming that the universe is more than 6,000 years old, but just you wait. Some day, they’ll correct that mistake too. They’ll come to realize that everything they think they knew about the supposedly ancient universe was wrong and that [Al Mohler’s interpretation of] the Bible was right. They’ll see. You’ll see. Some day all of these arrogant scientists will be hailing the truth and the genius of [Al Mohler and his interpretation of] the Bible.

Mohler is a gifted public speaker, so he makes this egotistical ignorance sound much more spiritually refined, but as you can see it boils down to something even less credible than the piffle being peddled by that so-called “science teacher” who claimed that stars are tiny little balls of fire suspended in a tiny little universe. At least that “science teacher” had the courage to admit to the kind of nonsense he was advocating. Mohler’s “just have faith that the science will be disproved” approach is more cowardly, refusing to take any specific stand on what it is he believes the coming “correct” science will actually say.

4. Reverse the polarity of the phlebotinum.

The same vast inter-stellar distances that provide stark evidence that young-Earth creationism is false also create problems for many would-be storytellers.

It’s a different kind of problem, of course. Gene Roddenberry and George Lucas weren’t claiming that their starship stories were true — much less that anyone who fails to embrace them as revealed truth will be damned for eternity. But even if you’re just telling a story for entertainment, you want it to seem possible and plausible. If the story you’re telling involves spaceships that travel between the stars, then you’re going to need to come up with some explanation for how they do that when we do not yet know of any way to achieve the faster-than-light speeds such travel would require. So the storyteller has two options: 1) Invent some new technology allowing for faster-than-light speed; or, far easier, 2) Reassure your audience that the characters in your story have done so and suggest just enough detail that your audience is willing to suspend disbelief enough to accept this.

Such suspension of disbelief is a standard part of any story involving not-yet-existent technology and/or magic. Such stories frequently involve problems arising from such technology/magic that will thus require some technical/magical solution. “Reverse the polarity!” the ensign cries from the bridge of the starship. What does that mean? We don’t know, but it sounds good enough to believe that the ensign knows, and so we as the audience are willing to play along. “Yes, yes,” we think. “Reverse the polarity, that might work!” (Reversing the polarity almost always works.)

Joss Whedon and the other writers for Buffy the Vampire Slayer didn’t have to worry about starships traveling faster than light (at least not until they started work on Firefly), but their stories were full of magical and mystical mumbo jumbo that needed to seem plausible if we, the audience, were to suspend disbelief and play along. They referred to this semi-explanatory appeal to the audience as “phlebotinum.”

Young-Earth creationism involves more phlebotinum than any science fiction or fantasy epic ever written. And it functions exactly the same. It is a magical talisman made of Handwavium, a bit of techno-babble and mumbo jumbo tossed forth to induce the audience to continue suspending disbelief so that they can continue to enjoy an impossible story.

I do enjoy such stories. I’m a long-time fan of good science fiction and fantasy tales. Heck, I’m also a long-time fan of bad science fiction and fantasy tales. And as a fan, I find a strange kind of enjoyment from trying to follow all the twists and turns of YEC’s labyrinthine logic. The extravagant work of imagination that falls under the heading of “flood geology,” for example, can be quite entertaining if one views it as a form of alternative-universe world-building — the author’s notes for an unwritten fantasy epic, perhaps. Sure, it’s utter nonsense as geology or biology or theology, and the entire thing is premised on an epic failure of basic reading comprehension. But bracket all of that and just regard it as a series of puzzles and problems to be solved and it’s kind of wacky fun. How are we going to get the koalas from Ararat to Australia? Oooh, tricky. What if we reverse the polarity?

A generation ago, most young-Earth creationists were still fruitlessly responding to the problem of telescopes by denying that space was as spacious as those telescopes showed it to be. Nowadays, though, the most vocal and most visible YECs actually accept the vast scope of the universe … sort of. They accept light-years as a measure of distance, but not as an indication of time.

So what does that mean for the problem of telescopes? Prepare to be dazzled by some world-class phlebotinum-spinning from Dr. Jason Lisle, an astrophysicist who works with Answers in Genesis. Ensign, reverse the polarity:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=83brK_yohRADr. Lisle starts with his personal favorite, an appeal to “The Anisotropic Synchrony Convention” — or, rather, an appeal to authority premised on the notion that you’ll take his word for it as a certified astrophysicist that he’s not torturously straining Einstein’s use of the word “convention” there. Don’t care for that one? Fine, how ’bout a “gravitational well” that makes the rest of the cosmos age more quickly than the Earth? (There’s a fun discussion of that idea here, with some links to its loopier proponents, whose “biblical” cosmology includes ideas such as the entire universe being surrounded by water.) What does he mean by a “gravitational well”? If you have to ask, then he must understand it better than you do, so he must be right.

But Lisle isn’t done yet. How about Carmellian physics? Boom. That’s a tachyon pulse right to the dilithium-crystal heart of any would-be skeptic.

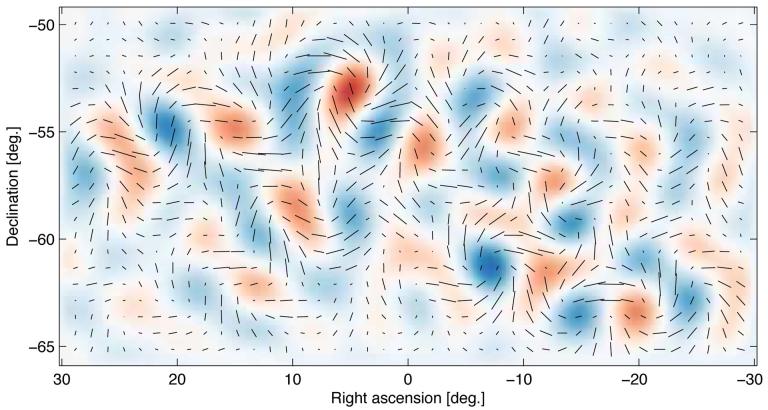

The great thing Lisle has going for him here is the intrinsic weirdness of real science. “Those who are not shocked when they first come across quantum theory cannot possibly have understood it,” Niels Bohr wrote. The stuff seems implausibly wacky and strange to a layperson — and even more so to a scientist. Lisle appeals to this strangeness directly by referring to problems with an outdated version of the Big Bang. Basically, he suggests that none of what he’s saying is any weirder than what someone like Neal deGrasse Tyson or Andre Linde is saying about “inflation” in the Big Bang. Lisle argues that his theories are no stranger than this:

Do you understand what you’re looking at there? Probably not. So how can you be sure that’s any more true than any of the phlebotinum Lisle is offering?

Lisle’s trump card, though, is the ultimate in phlebotinum — a holy grail made of kryptonite-encrusted unobtanium: “God may have used a supernatural mechanism. After all, God is not bound by the laws of nature as we are. Especially during the creation week …”

I like how that makes the story in Genesis 1 sound like Spring Break. Woo-hooooo! No rules! Party!

That oxymoronic phrase “supernatural mechanism” hints at the slippery trick Lisle is attempting here. If there is a “mechanism,” then it ain’t supernatural. (“What does God need with a starship?”)

Whether or not God is “bound by the laws of nature” is irrelevant here. What matters is that nature is bound by the laws of nature. Or else it is not. I appreciate Lisle’s head-feint in the direction of reasonableness, where he dismisses the Omphalos theory because it would make God a liar and would mean that “we really couldn’t trust our senses.” That’s correct, but it’s just as correct for any attempt to dismiss the problem of telescopes that simply says, “maybe it was something supernatural.”

My point here, though, isn’t about the specifics of Lisle’s reply to the problem of the light from distant stars. As with all appeals to applied phlebotinum, the specific details aren’t what’s important. What matters is the function of the appeal.

Lisle isn’t defending the claim of a young universe against the observable evidence that the universe is ancient. He is, instead, striking a bargain with the audience, offering a token gesture of semi-plausibility in exchange for which he hopes we will agree to suspend disbelief enough not to change the channel on the story he is telling.

In other words, this is not really a defense of young-Earth creationism or even a claim that young-Earth creationism is defensible. It’s not an argument presented to convince us that it is true. It is an invitation to play along.