As a general rule, the courts do not want to get entangled in questions of religious sincerity. That is neither their area of expertise nor an area — usually — in which they have any jurisdiction. Judges will go to great lengths to avoid any argument that requires them to evaluate the measure of religious devotion held by those making free exercise claims.

We saw this in the Supreme Court’s 2012 decision in Hosanna Tabor, which had to do with the application of the “ministerial exception” to workplace laws. The court’s unanimous ruling basically said (I’m paraphrasing): Ohelzno! You are not going to trap us into ruling on who is or who is not a legitimate “minister!”

Unfortunately, such evaluations of religious sincerity are sometimes unavoidable because they are part of the statute the courts are being asked to consider.

Think of conscientious objector status in the draft. At the beginning of the Vietnam War, CO status was mostly limited to religious claims — to those who had a long-standing and sincere religious commitment to pacifism. A life-long Quaker or Mennonite who could demonstrate the genuineness of their religious commitment could be granted CO status. But someone whose religious conversion to Quakerism occurred on the same day they got their letter from Selective Service would likely be denied.

Think of conscientious objector status in the draft. At the beginning of the Vietnam War, CO status was mostly limited to religious claims — to those who had a long-standing and sincere religious commitment to pacifism. A life-long Quaker or Mennonite who could demonstrate the genuineness of their religious commitment could be granted CO status. But someone whose religious conversion to Quakerism occurred on the same day they got their letter from Selective Service would likely be denied.

The law on CO status has changed a bit since then. One no longer needs to be a member of a historic peace church, nor to believe in a Supreme Being, in order to qualify as a conscientious objector. But the status is still only granted to those whose convictions are “deeply felt.”

And thus, like it or not, the courts are thus sometimes in a position where they’re required to judge a person’s depth of feeling.

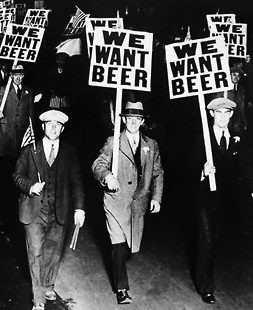

Or think back to the brief, strange period of Prohibition. The 18th Amendment prohibited “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.” Wine was — for more than a dozen years — unconstitutional.

But the Volstead Act — the set of laws enacting the 18th Amendment — provided an exemption for the use of such “intoxicating liquors” in religious rituals. The sacramental wine used by Catholic and Episcopalian* churches was therefore deemed legal, but only because the courts determined that their religious rituals were legitimate — that their purported religious devotion was sincere and genuine. The courts were, again, unavoidably required to make such judgments between legitimate and illegitimate religious practices and between sincere and insincere religious claims.

As those examples show, this usually happens whenever religious exemptions are carved out of otherwise generally applicable laws. Such exemptions are a kind of privilege, and thus invite chicanery. Don’t like Prohibition? Declare yourself Pope Bobby I of the Church of a Beer and a Bump. Now instead of prohibiting your daily postprandial custom, the Volstead Act actually compels the government to “ensure an ample supply” of legal alcohol for your “religious rituals.”

Alas for Pope Bobby, and for his ordained bartender, such religious claims can and will be challenged by legal officials. Pope Bobby will end up in court and some judge — like it or not — will have to make a ruling based on some evaluation of the sincerity of his religious claims and whether they are truly and genuinely “deeply felt.”

This is true whenever the law allows for a religious exemption. Unless the courts figure out a way to punt (as in Hosanna Tabor), such exemptions invariably entangle them in the subjective business of evaluating religious sincerity.

Such evaluations are a murky, messy business. The courts have a few tools for measuring such things, but none of them is definitive. A long-standing tradition seems to have a stronger claim to legitimacy, but new converts and new religions often have a more zealous and earnest devotion. Logical consistency and consistent behavior seem to indicate a strength of commitment and sincerity, yet many religions also insist that “there is none righteous, no not one,” and the lack of such consistency can’t be taken as proof of religious insincerity.

Thus, as a general rule, I think the courts are right to avoid questions of religious sincerity whenever and wherever possible. Even, sometimes, when the hypocrisy and insincerity of an abruptly discovered, brand-new “religious conviction” seems both glaringly obvious and legally significant.

As it happens, religious exemptions to generally applicable laws are kind of in the news just now. And, as it happens, Pope Bobby I and the Church of a Beer and a Bump just had a very good day in court.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

* Corrected. Thanks, Rev. Ref.