This excerpt from Norden, a Scandinavian TV documentary series, has been making the rounds. The show examines Scandinavian culture by bringing in outsiders and observing their reactions to what they find in these northern countries. In this clip, the show explores Scandinavian thoughts and attitudes about religion through the eyes of a politically conservative white American pastor from Georgia named Marty McLain.

Pastor McLain, like most white American evangelicals, seems like a Nice Person. He’s polite and friendly, and in general seems like a good sport. I would imagine he’s someone I could enjoy talking to, even though we clearly disagree on many, many important things.

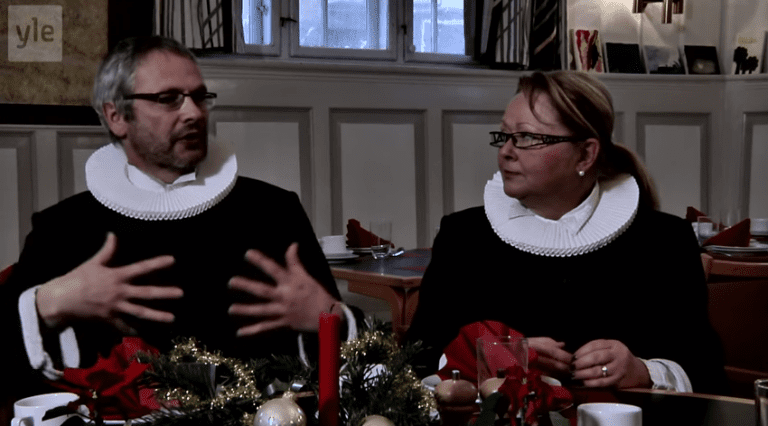

McLain seems a bit bewildered and saddened by his encounter with two Christian ministers from the Church of Denmark — one of them is a woman, they’re wearing those amazing clerical ruffs, and they don’t seem at all perturbed by same-sex marriage.

McLain’s thoughts after that meeting provides us with an excellent case study of why the largely unexplored “God hates shrimp” question is so essentially important for white evangelicals in America.

Here’s what Marty McLain says in the documentary:

I believe same-sex attraction is a sin. When it comes to homosexuality, the worst thing I could do to somebody is say, “You know, God made you that way and he wants you to stay that way. And God’s all for a homosexual relationship.” When you look in the Bible, you see what God says about homosexuality. I’d have to deny so much of scripture in order to give that type of counsel.

The implications and effects of what McLain is saying there are cruel and unjust, but McLain, as a Nice Person, isn’t thinking about those implications and effects. And it seems important to him that we appreciate that he does not intend to sound cruel or unfair.

But even more important than assuring others of his good intent is his apparent need to reassure himself of his good intent. That is the function of the anti-gay preacher boilerplate he invokes there about “the worst thing I could do” and about how it’s actually most loving for him to tell these homosexual sinners that being homosexual makes them sinners and that they must repent of being that. The function of that argument is purely internal. It’s not an attempt to persuade others. It’s not a statement addressed to others — not to LGBT people, or to Scandinavian TV producers, or to anyone else. It’s a therapeutic, self-help affirmation addressed to themselves — a way of telling themselves what they need to hear told them in order to stave off the creeping suspicion that they may be perceived as cruel and unfair.

And in order to stave off the even creepier creeping suspicion underlying that one — the fear that this perception might be accurate because they are, in fact, saying something and doing something that is cruel and unfair.

This mantra of self-assurance always includes a denial of personal responsibility: “It’s not me. It’s the Bible. The Bible is making me say these cruel things.”

Pastor McLain’s final statement in the quote above is something you’ll hear verbatim whenever you hear antigay Christians explaining why they believe they’re required to be antigay: “I’d have to deny so much of scripture.”

And that brings us back to the “God hates shrimp” question. McLain, et. al., say that it would be impossible for them to “deny” scripture — by which they mean to interpret any part of the Bible as anything less than a binding commandment.

But that is patently, obviously not true. It is not an accurate description of their actual relationship to the Bible.

The fact is that white evangelical Christians like Marty McLain routinely “deny so much of scripture” on a thousand other matters. “Shrimp” — referring to the Levitical prohibition against the “abomination” of eating shellfish — is just a memorable shorthand representative for all those other aspects of scripture that white evangelicals ignore, or “deny,” or otherwise dismiss as non-binding.

The point of “God hates shrimp” has nothing to do with suggesting that the Bible is full of lots of silly, frivolous things that we sophisticated people are free to disregard. The point is that — descriptively, as a matter of fact — even biblicistic white evangelicals do not act as though every unambiguous biblical command is binding for everyone today.

The Bible prohibits mixed fabrics. The Bible requires that all debts be forgiven every seven years. The Bible commands that all slaves be obedient to their masters. The Bible commands that all slaves be set free. The Bible commands us not to pray in public. The Bible forbids lending at interest. The Bible commands us to lend to anyone who asks without expecting them to repay us. The Bible forbids us to swear oaths or vows. The Bible tells us that all Cretans are liars and commands us to murder all Amalekites on sight. The Bible commands us to turn the other cheek.

Most Christians do not obey all of these biblical commandments. It wouldn’t be possible to obey them all, since some of them contradict one another. And yet we never hear this referred to as “disobedience,” or hear this described as “denying so much of scripture” the way we’re constantly being told that same-sex relationships are disobedient and involve “denying scripture.”

What’s the difference? Is this relationship to biblical commands as arbitrary, inconsistent and contradictory as it seems? Or is there some unspoken principle at work that requires McLain et. al. to treat the handful of passages condemning same-sex relationships as binding and essential while utterly ignoring the much larger collection of passages condemning lending at interest? What is the basis for treating some parts of scripture as “undeniable” and non-negotiable, while disregarding others so thoroughly that they’re scarcely ever mentioned, remembered or acknowledged?

Various branches of Christianity have various preferred hermeneutics — principled, systemic approaches to biblical interpretation that can guide us in understanding when a particular passage should or should not be seen as binding for Christians today. But white evangelicalism has no such principled hermeneutic. That’s due, in part, to the insistence that no such system is needed — admitting the need for such a hermeneutic would involve admitting that the Bible is not a simple, straightforward “guidebook for life” with a straightforward, face-value meaning that’s obvious and accessible to all people of good intent.

Ask most white evangelicals the “God hates shrimp” question and they’ll talk at great length, but none of that talk will constitute an answer to the question. Instead you’ll hear a weird mix of folklore, pulpit legend, and creative ad hoc responses to particular cases constructed after the fact on a case-by-case basis.

I suspect that most of that, again, is mainly for internal reassurance. It’s not primarily an attempt to answer the question, but mainly an attempt to reassure themselves that they needn’t worry about the question or its implications, because surely they must have some good answer, surely they must.