We could settle a lot of philosophical and theological arguments by simply commissioning more comprehensive polls. Are human beings basically good or are they depraved Augustinian wretches? Just ask them. Get a big enough representative sample with state-of-the-art methodology and we can put this question to rest with concrete, statistical certainty: “People are basically good” (Strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree).

When people don’t realize that I’m joking about that idea, they’ll push back, noting that most people are not reflective and self-aware enough to respond to such a question meaningfully. So, OK, I say, just adjust our survey to account for this — screening out all responses from those who do not agree or strongly agree with the statement “I am reflective and self-aware.”

That all may seem a bit silly, but this kind of thing really happens all the time. And sometimes Very Serious People take the results of such surveys Very Seriously.

Consider, for example, the spin around the ill-conceived Hartford Institute for Religious Research survey reported on here: “Most congregations avoid discussing politics, new study shows.”

I’d have gone with a different headline: “Congregational leaders, Hartford researchers, unable to define ‘politics.'” Because what we have here is a stunted, misleading, misconception of what does and does not constitute “politics” — one that leaves out any consideration of 90% of the political formation and political discipling that occurs in congregations.

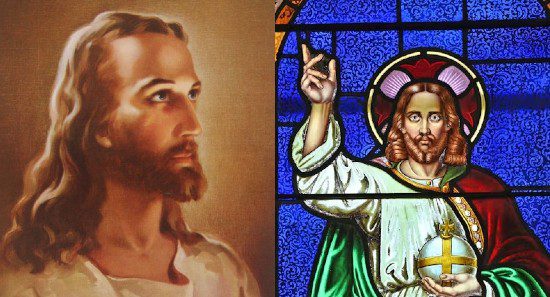

The basic framework here is that default political choices are “a-political” — neither political nor choices — but that anything other than those presumed defaults is both “political” and “chosen.” Some extremely “A Call for Unity” vibes in this notion of “avoiding politics.” So, for instance, if the painting on the left were hung in a Sunday school classroom, that’d be neutral and non-political, whereas the image on the right would be perceived as “politics.”

Basically, this survey — and the researchers attempting to interpret its results — don’t understand how the political views of a local congregation are expressed, maintained, instilled, and reinforced. They seem to recognize only explicit, propositional statements of partisan preference as “political” — a kind of “plenary verbal” politics, I guess. And thus they miss most of a congregation’s political instruction, which occurs through that which is presumed and that which, literally, goes without saying.

They also seem to view the composition of contemporary, self-selected, consumer-choice congregations as politically neutral or politically irrelevant. As though members attend these churches like 19th-century English villagers gathering at their local parish.

This is America. We have cars, not parishes. We shop around and go where we choose. And that choice is always, inevitably, political. Someone who drives past the local non-denominational mini-mega to get to the UCC church across town will most likely explain that decision in explicitly spiritual or doctrinal terms, and so will someone who drives past that UCC church to get to the non-denominational mini-mega evangelical one.*

Trusting those spiritual explanations at face value as the sole factor shaping those choices is about as foolishly naive as … well, as treating the responses to Hartford’s survey that way. (Or as naive as thinking that this even sillier survey must be legit because survey responses matter more than actual, lockstep allegiances and decades of unwavering behavior.)

But even on its own terms — even if what is treated as “politics” is limited to explicitly partisan election-focused verbal statements — this survey does not seem to find what it thinks it found.

Here’s a chunk of that RNS report on how this survey found congregations “avoiding politics”:

Even if members are politically active and many leaders are often outspoken about issues and candidates they support, most congregations make great efforts to keep politics out of the church. …

According to the report, 23% of congregation leaders identified their congregation as politically active, but only 40% engaged in what the report calls “overtly political activities” over 12 months, mostly infrequently.

The report measured congregations’ level of political engagement by looking at seven categories of political activities, including distributing voter guides, organizing protests in support or opposition of a policy, and inviting a candidate to address the congregation. A minority of congregations engage in any of the above; 22% handed out voter guides; 7% asked a candidate to speak to the congregations; and 10% lobbied for elected officials.

If these folks are making “great efforts to keep politics out of the church,” they’re doing a lousy job of it.

Perhaps the biggest problem here is that Hartford’s study was administered as a survey, but it was received as a test — a test with obviously right and wrong answers. The congregational leaders “surveyed” were keen on passing that test and supplying the respectably “correct” answers.

So this is all about as meaningful as a survey declaring its findings with a headline proclaiming “Majority of Americans Transcend Partisan Ideology” because they agreed or strongly agreed with statements like “I am an independent thinker” and “I like to consider all the options and choose for myself” and “Unlike my hidebound, sheeplike neighbors, I personally transcend blinkered petty partisanship, soaring far, far above it in an ethereal realm of individual virtue.”

Surveys are less reliable when their questions have potential answers that are widely perceived as “more respectable” than others. Surveys are less reliable when their questions have potential answers that all respondents to flatter themselves. And surveys are especially useless when respondents have the option of answering in a way that is both “respectable” and self-flattering. That’s what we have here and — surprise, surprise! — most respondents gave the answers they perceived as respectable and self-flattering.**

The organizers of this survey seem pleased with the results — with the respectable confirmation that most respondents gave what they perceive to be the respectable answer. That strongly suggests that they were unaware of the ways in which it may have been conducted to encourage such correct and properly “respectable” answers.

All of this is quite separate from anything to do with Matthew Avery Sutton’s recent unsettling of white evangelical historiography. Sutton offered a plain-language description of 20th-century white evangelicalism that caused a bit of a stir — for some folks, anyway. He wrote:

I argue that post–World War II evangelicalism is best defined as a white, patriarchal, nationalist religious movement made up of Christians who seek power to transform American culture through conservative-leaning politics and free-market economics. Contemporary evangelicalism is the direct descendent of early twentieth-century fundamentalism, North and South. Both movements are distinct from Antebellum forms of Christianity. There is no multi-century evangelical throughline.

That description continues to enrage those invested in the idea that the 81% of MAGA-fied evangelicals are an aberration and an uncharacteristic minority besmirching the good name of the rest of us, the worthy heirs of William Wilberforce. (Or something.) Challenging the respectable nonpartisanship of white evangelicalism in the same paragraph in which he challenged evangelical primitivism upset some folks.

John Fea is among the angrier critics of Sutton and he latched onto Hartford’s survey — which did not focus specifically on evangelical congregations — as some kind of rebuttal of Sutton’s description, sarcastically asking: “Where are all these nationalist evangelicals who ‘seek to transform American culture through conservative-leaning politics and free market economics?’”

Where are they? They’re right there, trying their best to give the correct answers and to pass the test, just like the rest of the congregational leaders who responded. They’re a-political and non-partisan. Just ask ’em, they’ll tell you.

The point here is not that Sutton is right and Fea is wrong (although, yeah, Sutton is right and Fea is wrongity wrong wrong wrong here), but that surveys like this one are useless as tools for evaluating any of this one way or another.

If Sutton’s critics really think otherwise, then their next step is simple: Create a more precisely targeted survey to disprove Sutton’s description. Send every evangelical pastor a one-question survey asking them to evaluate his argument above on a Likert scale.

Can you guess how they’ll respond? I can. It’s not hard.

And so, when the results come back finding that the overwhelming majority of evangelical pastors “disagree” or “strongly disagree” with Sutton’s description, his critics can do a victory lap, high-fiving one another, because they will have “proved,” once and for all, that evangelicalism is not a white, patriarchal, nationalist religious movement made up of Christians who seek power to transform American culture through conservative-leaning politics and free-market economics.

I mean, what more “proof” could anyone need?

* Almost nobody chooses between a PCUSA and a PCA church based on which one is closer. The choice is usually based on the doctrinal differences between those two Presbyterian denominations. Those doctrinal distinctions parallel political distinctions. For example: PCUSA churches ordain women; PCA churches do not. Women preach in PCUSA churches and are forbidden from preaching in PCA churches.

But none of that, according to Hartford’s survey, has anything to do with “politics.”

** They are, alas, mistaken. As ever, flattery misleads about what it actually flattering and self-praise diminishes that which is praiseworthy. The airy, above-it-all, “a-political,” “non-partisan” or “trans-partisan” attitude encouraged by smarmy respectability is all just a fancy costume for irresponsibility and a refusal to commit to the necessary work of choosing and of owning the repercussions of the choices we must make. It’s not any more impressive or admirable than any other form of lukewarm, Laodicean cowardice. But it always gets a round of applause from the smarmily respectable op-ed columnists who have convinced themselves that their own political preferences will be more persuasive if they don a mask of disinterested “nonpartisanship.”