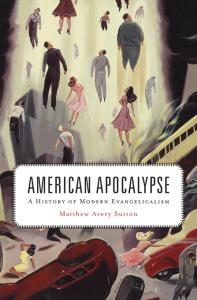

Matthew Avery Sutton just published one of those pot-stirring academic articles that changes things.

We could describe this in a way that makes it all sound abstract or arcane — “academic” in that other sense of the word, suggesting that something is impractical or irrelevant outside of the classroom. In one sense, after all, this is all very niche. We’re talking about an article in the Journal of the Academy of American Religion that summarizes and synthesizes the criticisms of the once-consensus historiography of American evangelical Protestantism and proposes a new approach that can better account for and respond to the substance of those criticisms. The title of Sutton’s article — “Redefining the History and Historiography on American Evangelicalism in the Era of the Religious Right” — isn’t exactly clickbait.

In the very particular niche of historians who study American evangelicalism, Sutton’s article is making a big splash. This is, I think, going to be one of those before-and-after articles. Folks are already fighting over it. Even those who reject its arguments are going to have to contend with it for the foreseeable future. Everything that’s published on the history of “evangelicals” or on “evangelicals” in history over the next few years is probably gonna need a “(Sutton 2024)” footnote or two in there somewhere.

In the very particular niche of historians who study American evangelicalism, Sutton’s article is making a big splash. This is, I think, going to be one of those before-and-after articles. Folks are already fighting over it. Even those who reject its arguments are going to have to contend with it for the foreseeable future. Everything that’s published on the history of “evangelicals” or on “evangelicals” in history over the next few years is probably gonna need a “(Sutton 2024)” footnote or two in there somewhere.

But this isn’t just an academic matter because, as it turns out, “the history and historiography on American evangelicalism” isn’t exclusively a matter of concern for religious historians or American historians. It’s also an ongoing obsession for American evangelicals themselves. (So much so that I have often joked here that the definition of an evangelical is a Protestant Christian who is preoccupied with defining “evangelical.”)

Historians have a practical, professional need for a usefully accurate definition of “evangelical” and “evangelicalism.” If you’re trying to write about the history of a group then you need some clear, meaningful way of distinguishing that group from other groups. That’s relatively easy if you’re writing about, say, Roman Catholics — a group whose membership is not difficult to determine and a term that has been used, within and without that group, in a fairly consistent manner over time. It’s a lot harder for a more nebulous group or tradition or “stream” of Christianity such as “evangelicals.” Evangelical Christians have not always (or perhaps even usually) self-identified using that term and the term has meant very different things in different places over time.

For a historian writing about evangelicals, then, it’s a bit like setting out to write a history of “nerds.” It’s a meaningful category, and an important one (you’re reading this on the internet, after all), but it’s also a category whose boundaries have always been disputed, and whose boundaries have shifted over time. The term has been, at various times, deliberately branded, re-branded, and weaponized as both a pejorative and a badge of honor. You can’t write about nerd-dom without trying to cut through all of that by proposing some clearer definition to shape and bound your project.

And so historians propose definitions of and boundaries to evangelicalism in pursuit of clarity. Evangelicals, on the other hand, propose definitions of and boundaries to evangelicalism in pursuit of authority. That authority might be pursued in the hopes of settling theological disputes within evangelical Christianity. More often, though, that authority is pursued in the hopes of increasing market share.

It’s not accurate to say that debates among evangelicals about the definition of “evangelical” are only or exclusively about money and power, but money and power are always at stake in such debates. Those debates and the various competing definitions they produce are never wholly disinterested, and thus never wholly trustworthy. And because of that, many evangelicals have themselves come to defer to historians as a kind of neutral-party referee for defining who they are. “The History and Historiography on American Evangelicalism” is thus never simply a matter of academic observation, it changes the thing it observes. Ask the National Association of Evangelicals to define “evangelicalism” and they won’t tell you who they say they are, but will instead refer you to the Bebbington Quadrilateral — an artifact of “the History and Historiography on British Evangelicalism” never intended to apply to 21st-century Americans.

So it won’t just be religious historians and American historians studying white evangelicals who are arguing about Sutton’s article. The article will also spark a thousand arguments among white evangelicals themselves.

I will have something to say about those arguments because, as it turns out, I’m a footnote in this history — literally.

Two footnotes, actually. The one that doesn’t mention me by name is the more pertinent one here. That footnote says this:

In the 1960s and 1970s, younger evangelicals fought to broaden the movement, to make it more inclusive and less racist, nationalist, patriarchal, and wedded to free market economics. They mostly failed. See Swartz 2012 and Gasaway 2014.

I was younger than the “younger evangelicals” in that fight. After they mostly failed in the 1960s and 1970s, I went to work for them and helped them to continue to mostly fail in the 1980s and 1990s. I am intimately, personally, and professionally familiar with that failure. It would constitute the largest chunk of my résumé if not for the fact that, being a failure, it has left me as someone who no longer needs to bother with having a résumé.

The references in Sutton’s footnote refer to two fine books by David R. Swartz (Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism) and Brantley W. Gasaway (Progressive Evangelicals and the Pursuit of Social Justice). I worked for and with most of the key figures in those books throughout the 1990s. Seeing that work relegated to a single footnote in Sutton’s article where it is summed up in three words — “They mostly failed” — is a bit harsh, but it’s not inaccurate. (I feel a bit like Arthur Dent reading the two-word entry for our home planet in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy: “Mostly harmless.”)

That (mostly harmless) history and personal history of “the evangelical left” and “progressive evangelicals” seems to be playing a role in the pushback against Sutton’s article. The existence of such a dissenting faction is being held up as a counter to Sutton’s stark contention that “Post–World War II evangelicalism is best defined as a white, patriarchal, nationalist religious movement made up of Christians who seek power to transform American culture through conservative-leaning politics and free-market economics.”

The invocation here of “the evangelical left” — of the Ron and Jim and Tony Show — as somehow a refutation of Sutton’s description gives me an opportunity to replay Marshall McLuhan’s cameo in Annie Hall. We’ll get to that in Part 2.