Swearing an oath on the Christian Bible is problematic, at best. This is a book, after all, that includes the words of Jesus Christ himself commanding his followers not to swear oaths:

Again, you have heard that it was said to those of ancient times, “You shall not swear falsely, but carry out the vows you have made to the Lord.”

But I say to you, Do not swear at all, either by heaven, for it is the throne of God, or by the earth, for it is his footstool, or by Jerusalem, for it is the city of the great King. And do not swear by your head, for you cannot make one hair white or black.

Let your word be “Yes, Yes” or “No, No;” anything more than this comes from the evil one.

That’s unambiguous and pretty strongly worded. Swearing by or swearing on something, Jesus said, is “evil.”

Granted, this is from Matthew 5, from the Sermon on the Mount. And over the past 2,000 years, we Christians have developed an impressive body of work designed to excuse ourselves from being bound by anything Jesus said in that particular sermon.

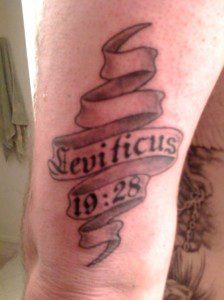

Still, though, the words of Jesus quoted above are printed on the pages of the Christian Bible, so placing one’s hand on that Bible to swear an oath by it seems like a self-negating act — or a bit of ironic performance art, like the guy who got a tattoo of Leviticus 19:28 (“You shall not make any gashes in your flesh for the dead or tattoo any marks upon you”).

Here in Pennsylvania, though, state law requires witnesses testifying in court to swear an oath on the “Holy Bible.” The assumption for this statute seems to be that the Bible is revered as an artifact, but that no one cares what it actually says. That assumption may be broadly accurate, but that doesn’t make it any less absurd.

The point of this statute is that we want witnesses testifying in court to recognize the solemnity and gravity of their role, and we want them to make a serious and emphatic affirmation that they will speak the truth.

There are two possible ways the requirement to swear on the Holy Bible can serve those functions. The first relies on superstition and magical thinking. The second relies on personal commitment.

In the superstitious system, the Bible is seen as a kind of magical talisman. The physical book is, itself, a source of magical or spiritual power that works upon the witness to compel them to fulfill their vow. Note that it doesn’t matter whether or not the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and its courts actually believe this, the efficacy of this is based only on whether the majority of witnesses do. And if nearly all the witnesses sworn to testify in Pennsylvania’s courts did believe this — if they thought of the Bible as a magical book and viewed it with the same fearful, superstitious awe as the pirates in Treasure Island did — then requiring those witnesses to swear on the Holy Bible would be a functionally effective way of inducing honest, serious, truthful testimony from them.

But while such a superstitious policy might sort of work, it would still be bad policy. We don’t really want a judicial system in which the majority of witnesses testifying are as illiterate and inconstant as the crew of the Hispaniola. Also, any system that relies on superstition will wind up having to promote superstition. Anyone — religious skeptics, adherents of other religions, or actual Bible-reading Christians — who publicly challenged this idea of the Bible as a magic item would be a threat to the integrity of the courts and would need to be silenced, with the state officially refuting their claims and promoting the talismanic superstition the witness system required. Inevitably, the state would wind up spreading lies in an attempt to ensure that witnesses tell the truth, and that’s not going to end well.

That leaves us with the second possible basis for Pennsylvania’s requirement that witnesses swear on the Holy Bible, which is the idea that by swearing on the Bible, the witness is expressing a personal commitment. The witness — all witnesses and every witness — is presumed to share a general cultural reverence for the Holy Bible as a sacred text. The physical book itself, in this view, is not regarded as a powerful magical item, but it represents something the witness is expected to regard as serious, significant and personally meaningful. The power here, in other words, doesn’t arise from the book itself, but from the witness’ personal regard for it.

That makes sense — to the extent, at least, that “swearing” on anything makes sense. Swearing on the Holy Bible is the same as swearing on your mother’s grave. It’s a way of saying, “Let me convince you that I am serious about what I am about to say by referring to something that you know I take seriously.” No such claim can ever be wholly persuasive. It’s an appeal to be considered trustworthy, not evidence of trustworthiness. But it does provide an emphatic way for a witness to state the seriousness of their intent to be truthful. And it’s more elegant than, for example, something like this:

“Do you swear to tell the truth?”

“I do.”

“Do you really swear to tell the truth?”

“I really do.”

“Do you really, really, really swear to tell the truth?”

“I really, really, really do.”

“Pinky swear?”

“Pinky swear.“

But while swearing on a Holy Bible may be more elegant than that, it’s not substantively different. No oath can be. Jesus had a point with that “Let your ‘yes’ be ‘yes’ and your ‘no’ be ‘no'” bit. Someone who intends to say “yes” when the truth is “no” doesn’t suddenly become truthful just because we invoke their dead mother’s memory or a sacred text or anything else they may esteem.

The problem with Pennsylvania’s Holy Bible requirement is the mistaken assumption that every witness can be expected to share a deep reverence for the Christian Bible. That is simply not the case. It is, in fact, inaccurate. Not every Christian witness shares the kind of reverential regard for the Bible that would serve to solemnize their oath. And, more importantly, not every witness is a Christian.

Which brings us to the news hook for this post, “Judge Rules Pa. Muslim May Not Swear on Koran“:

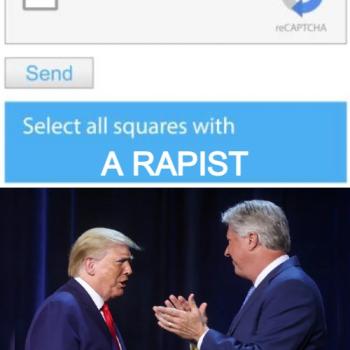

A Pennsylvania judge forbade a Muslim woman from swearing on the Quran before taking the witness stand in a custody dispute. The ruling upholds a state law that requires witnesses to swear on the Christian Bible or make a non-religious affirmation before offering testimony.

The woman had argued that the state’s law violated her religious liberty rights and exhibited a preference for Christianity over Islam and other religions.

She’s got a strong First Amendment case, I think. The Christian Bible requirement for Pennsylvania courts seems like a clear violation of the Establishment Clause, and as a result this woman’s free exercise rights seem to have been violated.

Pennsylvania’s law seems unconstitutional — which is to say that Pennsylvania’s law seems unlawful.

That’s important, but it’s not my main complaint here. My main complaint is that Pennsylvania’s law is incredibly stupid and counter-productive. The function of the Bible in such oath-swearing is to solemnize the oath by referencing a symbol the witnesses themselves regard with reverence. If the witnesses do not belong to a sect that regards a sectarian text with reverence, then that text cannot function as a symbol to solemnize their oath.

Asking a Muslim or a Jew or an atheist to swear on a Christian Bible undermines the force of the ritual. If there’s any Christian reading this who doesn’t understand that, simply flip the script. Imagine you’re being asked to swear on the Koran. Or on the Bhagavad Gita. Or on any other text that you do not personally revere. Would reference to that text in any way enhance or solemnize your oath?

Requiring witnesses to swear by a text they do not personally revere adds nothing. It can even have the opposite of the intended effect — rather than making the oath seem more serious, it can make it seem less so.

Ask me to swear to tell the truth and I will take that seriously. Ask me to place my hand upon a VHS copy of Ernest Goes to Camp and to swear upon the sacred memory of blessed Vern and you will have introduced the suggestion that perhaps I don’t need to take this quite so seriously after all.

An oath is only meaningful insofar as it is meaningful to the individual swearing it. It’s just dumb to disallow witnesses from swearing by the symbols they personally revere while requiring them to swear by symbols they don’t.

If Pennsylvania is going to insist that witnesses swear on holy texts, then it should have the good sense to make sure that such witnesses are using their own holy texts and not somebody else’s.

I’d prefer that my state just dispense completely with the unbiblical use of Bibles and holy texts in these swearing-in rituals. The only text that should be invoked when witnesses are sworn in is the only text that has any real power to compel them to be truthful: the text of Pennsylvania’s perjury statute.