(Originally posted January 18, 2010. This got lost in the migration from TypePad to WordPress, recovered and reposted for the archives here thanks to the Internet Archive Wayback Machine.)

Tribulation Force, pp. 133-139

As we turn our attention from Buck back to Rayford, I realize I will need to amend one point from what I said last week.

Discussing the abstract love of Tim LaHaye & Jerry Jenkins’ brand of evangelical Christianity, I noted that such love expresses itself apart from “any consideration of deeds, actions and choices.” But watching poor Rayford squirm in the pages we’re looking at this week reminds us that there is one — and apparently only one — action such love requires, or rather demands, as a demonstration that it is genuine. It demands that evangelicals evangelize. And it requires a peculiar form of evangelizing.

We discussed this earlier:

Contemporary American-style evangelism is made even stranger by the fact that it seems devoid of content. It’s become a turtles-all-the-way-down exercise with no apparent real bottom. Evangelism means, literally, the telling of good news. Surely there must be more to this good news than simply that the hearers of it become obliged to turn around and tell it to others. And those others, in turn, are obliged to tell still others the good news of their obligation to spread this news.

That may be an effective marketing strategy, but what is the product? There doesn’t seem to be a product — only a self-perpetuating marketing scheme. It’s like Amway without the soap.

The model here may seem familiar. There are computer programs designed to work this way — programs that have no function other than to replicate themselves, creating duplicate copies that, in turn, have no function other than to create even more duplicates. We call such programs “viruses.”

The invitation to become a computer virus is not perceived by most human listeners as Good News.

LaHaye and Jenkins would take issue with my description of evangelism here. They would argue that I’m leaving out the most important bit: Hell. Factor Hell into the equation and the self-perpetuating marketing scheme seems more logical. It may be contentless, but it’s not ineffective: the viral carriers are spared an eternity of torment in Hell.

Nathan Heflick explored the logic of this in a recent Psychology Today blog post reflecting on the Rev. Pat Robertson’s ridiculous comments following the Haitian earthquake.

We know Robertson believes the Bible is 100-percent literally true. And we know that Robertson believes that anyone who doesn’t believe what he does is going to Hell.

Once you hold those two positions, it sort of opens up a giant can of possibilities for what you can, in your own mind, endorse. Once a person can be justified to suffer in a pit of fire for eternity, then an earthquake is probably not viewed with near the same level of tragedy.

For Robertson, God is saving Haitians from his worst punishment (Hell) by trying to send a warning sign to them via this earthquake. …

So while most of the world sees this earthquake for what it is — a tragedy of immense proportions — Robertson sees it as an act by God to save the Haitians from themselves and Hell. God just doesn’t want his people to suffer in a pit of fire eternally. So God kills off a few in the meantime.

If you accept the premise of eternal and infinite torment in Hell, then the basic calculus there makes sense. Eternity is longer than a lifetime, and Hell is worse than any imaginable earthly suffering, so there’s a certain logic to being more concerned with saving others from an eternity of Hell than with assisting them with any earthly suffering, need, injustice or oppression.

L&J and their disciples — on and off the page — would go further. They would point out that eternity is infinitely longer than time and that Hell is, by definition, infinitely worse than any earthly suffering. By comparison then, we can say with mathematical certainty that there is no comparison. Any earthly suffering or injustice is utterly inconsequential compared to the obligation to save others from an eternity in Hell.

It is therefore Rayford Steele’s duty — the duty of every Christian — to disregard all earthly sorrows and temporal woes in order to focus fully on the far greater matter of eternal salvation from the fires of Hell. And that is what we see Rayford doing here in this chapter with a single-minded determination that is almost admirable.

Accept that Hell is real and that it is infinitely more important than any earthly concerns and suddenly the very things that might compel you to attend to this-worldly needs and injustices — compassion, empathy, faith, hope, love — become reasons not to do so.

Accept that Hell is real and that it is the eternal destination of anyone who fails to pray the saving prayer and you become morally obliged — compelled — to stop wasting your time responding to any merely earthly, temporal matters, no matter how grievous or important they might at first seem. They are nothing compared to Hell.

And because of Hell, you are a monster unless you drop everything else and become like Rayford Steele — the sort of person who cannot allow himself to care if his co-workers all regard him as a pushy jerk and a nutcase zealot. If Hell exists then you must stop giving change to homeless people and you must, instead, start handing them evangelistic tracts. Keep your spare change. You’re going to need it to buy more tracts.

I’m not trying in the preceding paragraph to paint this argument in a flattering light, but every American evangelical Christian has heard this exact theme in dozens of sermons.

These half-dozen pages recounting Rayford’s conversation with his boss, Earl, constitute yet one more such sermon. Rayford Steele is presented here as a role model of passionately sincere faith, an exemplar of the kind of devotion that L&J want every Christian to have, or at least to feel guilty about not having.

Earl sat in the only other chair in his cluttered office, the one behind his desk. “We’ve got a problem,” he began.

“Thanks for easing into it,” Rayford said. “Did Edwards write me up for, what did you call it, proselytizing?”

Have you gotten into trouble at work for proselytizing? No? Why not? Don’t you care that the people you live with are doomed to spend an eternity in the endless, burning fires of Hell? I suppose you think keeping a clean personnel file and having people not awkwardly avoiding you all the time is somehow more important than that. Monster.

“That’s only part of the problem,” Earl tells Rayford. Which turns out to mean that Edwards isn’t the only one who “wrote him up” for proselytizing. Earl doesn’t say right off who else complained, and Rayford doesn’t ask him, so they spend a good chunk of these pages going in circles and repeating themselves without actually moving the conversation forward for one another or for the readers. This is kind of a Jenkins trademark. It’s like reading the “Who’s on First?” routine, except without the rhythm, the wordplay and the comedy.

They pause, briefly, in this repetition to note that just as Rayford is the very model of the workplace evangelist, so too is Earl the model for those who inexplicably choose not to accept the invitation to avoid an eternity of torment and decline the chance to convert:

“You hit me with all that church and Rapture stuff, and I was polite, wasn’t I?”

“A little too polite.”

“But I took it as a friend, just like you listen to me when I brag about my kids, right?”

“I wasn’t bragging about anything.”

“No, but you were excited about it. You found something that gave you comfort and helped explain your losses, and I say, great, whatever makes your boat float. You started pressing me about coming to church and reading my Bible and all that, and I told you, kindly I hope, that I considered that personal and that I would appreciate it if you’d lay off.”

“And I did. Though I still pray for you.”

“Well, hey, thanks.”

I give Jenkins some credit here for at least trying to imagine how Rayford’s aggressive evangelism might seem from the point of view of one of his targets. But he can’t follow that line of thinking very far because that’s not his primary goal in the conversation above. What he mainly is trying to communicate there is something like, “See? You can just say ‘No, thanks,’ respectfully without treating us like we’re crazy or getting us in trouble with the boss. You should be grateful that we care about you.”

One of Jenkins’ favorite illustrations of this point is his imaginary neighbor with the purple necklace. Here’s a version from an old interview on CNN:

“If I had a neighbor who truly believed that if I didn’t wear a purple necklace, I would never get to Heaven, I would go to Hell, I would probably think he’s crazy. I would scoff and laugh. But if he didn’t tell me, I’d be a little offended.”

His point is that by sharing his belief — as ridiculous as it may be to believe in a magic purple necklace instead of a prayer incanting a set of magic words — the neighbor would be showing that he cared, that he wanted Jerry to be saved from Hell. And just as Jenkins would be grateful to his neighbor for this expression of concern through proselytization, so too he feels everyone else ought to be grateful to him and LaHaye for their proselytizing.

I appreciate the point, and it’s not a bad reminder that we should appreciate such concern even when it’s expressed rudely. When someone insists that we have to listen to what they’re saying, that person may really be acting out of what they perceive as our best interest — even if it might never occur to them that they might also want to listen to us.

And that’s the problem with Earl as the model of a grateful evangelistic target. Earl listens to Rayford’s story, but he doesn’t have his own story. If Jenkins ever found himself in the scenario from his purple-necklace illustration, he wouldn’t just stop with “Thank you for your concern for my eternal soul.” He would go on to say, “No, no, no. that’s not how you save your eternal soul from Hell. I’ll tell you how it really works.” But he can’t imagine that other people — the ones he’s evangelizing — might also have their own stories, their own faiths. And he can’t imagine that any such faith might be centered around anything other than what is to him the paramount question: How to escape eternal torment in Hell.

Through the character of Earl, Jenkins offers his best guess as to why people sometimes claim to be insulted or offended by an evangelist’s heartfelt desire to save them from Hell. :

“You said you just cared about me, which I appreciate, but I said you were getting close to losing my respect.”

“And I said I didn’t care.”

“Well, can you see how insulting that is?”

“Earl, how can I insult you when I care enough about your eternal soul to risk our friendship? … What people feel about me isn’t that important anymore. Part of me still cares, sure. Nobody wants to be seen as a fool. But if I don’t tell you about Christ just because I’m worried about what you’ll think of me, what kind of friend would I be?”

Earl sighed and shook his head.

Yes, Earl — the surrogate here for every nonbeliever ever submitted to an unwelcome evangelistic sales pitch — bows in defeat to Rayford’s superior logic. He tried to be insulted, but once Rayford explained that he had no reason to be anything other than grateful, he concedes the point.

Nevermind that Rayford’s idea of evangelism is not to sing “Amazing Grace,” but rather to sing, “You’re a wretch, you’re lost, you’re blind …” which isn’t quite as winsome. And nevermind that Rayford, like many evangelizing evangelicals, seems more driven than called, and less concerned with the fate of Earl’s soul than he is with keeping up his sales figures for his very demanding boss.

[Mamet]”We’re adding a little something to this month’s evangelism outreach. As you all know, first prize is a Cadillac Eldorado. Anybody want to see second prize? Second prize is a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re going to Hell because apparently you’re not passionately sincere enough.”[/Mamet]

There’s another two pages around the mulberry bush discussing what Rayford did or did not say to Edwards that should or shouldn’t have offended him (all of which is made more confusing than it needed to be by the fact that Edwards’ first name is “Nicky”). And then finally, five pages and 20 laps in, Earl tells Rayford that his flight instructor in Dallas also wrote a formal complaint about his proselytizing.

This, apparently, is a sign that some Nefarious Plot is afoot. Because, Rayford insists, his flight instructor in Dallas is the one person he didn’t try to convert:

“In fact, I felt a little guilty about it. I said hardly anything to him. He was pretty severe, giving me the usual prattle about what he was and wasn’t there for.”

“You didn’t preach at him?”

Rayford shook his head, trying to remember if he had done or said anything that could be misconstrued. “No. I didn’t hide my Bible. Usually it’s in my flight bag, but I had it out when I first met him, because I’d been reading it in the van. Hey, are you sure this complaint didn’t come from the van driver? He saw me reading and asked about it, and we discussed what had happened.”

“Your usual.”

Rayford nodded. “But I didn’t get any negative reaction from him.”

Our role model evangelist, you’ll note, is impeccably egalitarian — equally concerned for the soul of his van driver as for the soul of his boss. And L&J even supply some tips for how readers can better witness — the old Conspicuously Reading the Bible So As to Prompt a Conversation About Salvation From Hell trick (also known as the Reverse Philip).

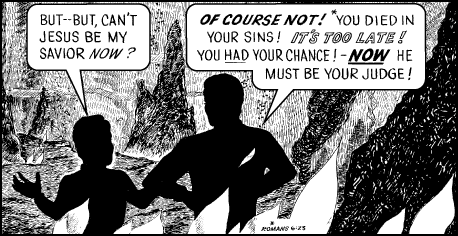

In terms of effectiveness, this works about as well as many of the other popular “witnessing tools,” such as the “I Found It” button, the Jack Chick comic, the WWJD bracelet, the cross lapel pin and the Christian T-Shirt. To date, no one, ever, anywhere has converted to Christianity even in part due to a Christian T-Shirt, but hey, it’s bound to happen someday, right? (So keep buyin’ ’em suckers, er, I mean, brothers and sisters in Christ.)

The problem with all of these is that they’re not really meant to create conversation or to persuade. They’re designed, rather, to be tribal symbols, reinforcing identity within the tribe while warning outsiders to stay away.

Members of the tribe will read these pages describing Rayford’s almost unfailing evangelism and recognize it as that familiar sermon, yet another exhortation and reminder that we have no time to be distracted by this-worldly concerns and that we are compelled to keep our focus only on what matters most: saving souls from Hell.

Every variation of this sermon just assumes — like Pat Robertson and his critic Nathan Heflick both seem to do — that this belief in eternal torment in Hell is something that comes from believing that “the Bible is 100-percent literally true.” But this idea of Hell and the conclusions L&J draw from it literally cannot be found in the Bible.

The Bible actually has very little to say about the subject of Hell. Most of the dozens of different books that make up the Christian scriptures don’t mention it at all, let alone suggest that it should be the central organizing principle of our faith. Those books, instead, devote themselves to considering the character of God and the character of God’s people — and little of what they have to say about either of those subjects is compatible with the logic of Hell presented by Pat Robertson or L&J.

The biblical case for Hell as a place of eternal, infinite torment turns out to come down to three passages in the New Testament. And each of those passages — the parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man, the parable of the Sheep and the Goats, and the concluding chapter of Revelation — explicitly states that Hell is the destination reserved for people who failed to respond to earthly suffering, need, injustice and oppression.

Every passage that mentions something like an eternity of suffering in Hell, in other words, does so for the purpose of driving home the exact opposite of the lesson L&J take from them.

The condemned in Revelation are judged “according to what they had done” here on earth. The rich man is sent to fiery torment exclusively due to his neglect of a single suffering neighbor. The goats are banished to an eternity of wailing and gnashing of teeth for their failure to feed the hungry, clothe the naked, comfort the lonely and tend the sick.

Over here in literate world, we can look at each of those passages in turn and consider what they are about, what they mean and are intended to communicate, and how bizarre and distorting it would be to regard any of them as providing the basis for a belief in a “literal” Hell. But my aim here is not to try to convince L&J to come join us over here in literate world. We haven’t time to try to teach them how to read. But let me instead just point out to them that by their own standards, according to their own illiterate rule of literalism, every passage they might cite in defense of their exclusive focus on the otherworldly salvation of souls from Hell explicitly demands the opposite conclusion.

If you believe in a “literal” Hell based on what the Bible teaches, then you must also believe that the only way to avoid going there has nothing to do with proselytizing or praying the sinner’s prayer. If you want to avoid Hell, you must invite Lazarus into your home, clean his wounds and feed him at your table. If you want to save others from damnation in Hell, you must convince them to join you in feeding these beggars at the gates, these least of these.

If you do that — if you make earthly, this-worldly suffering, need, injustice and oppression your primary focus, your paramount concern — then you may be saved from Hell and may one day join Lazarus and all the other poor beggars up in Heaven.

The literal Hell of the Evangelists turns out to be the exact opposite of the literal Hell of the evangelizers.